It's been such a busy week a barely know where to begin. But I'll start with

Hilton Als's (at right, in a horrible cellphone photo) provocative talk, "The Exile," which was part of this year's One Book One Northwestern series, focusing on

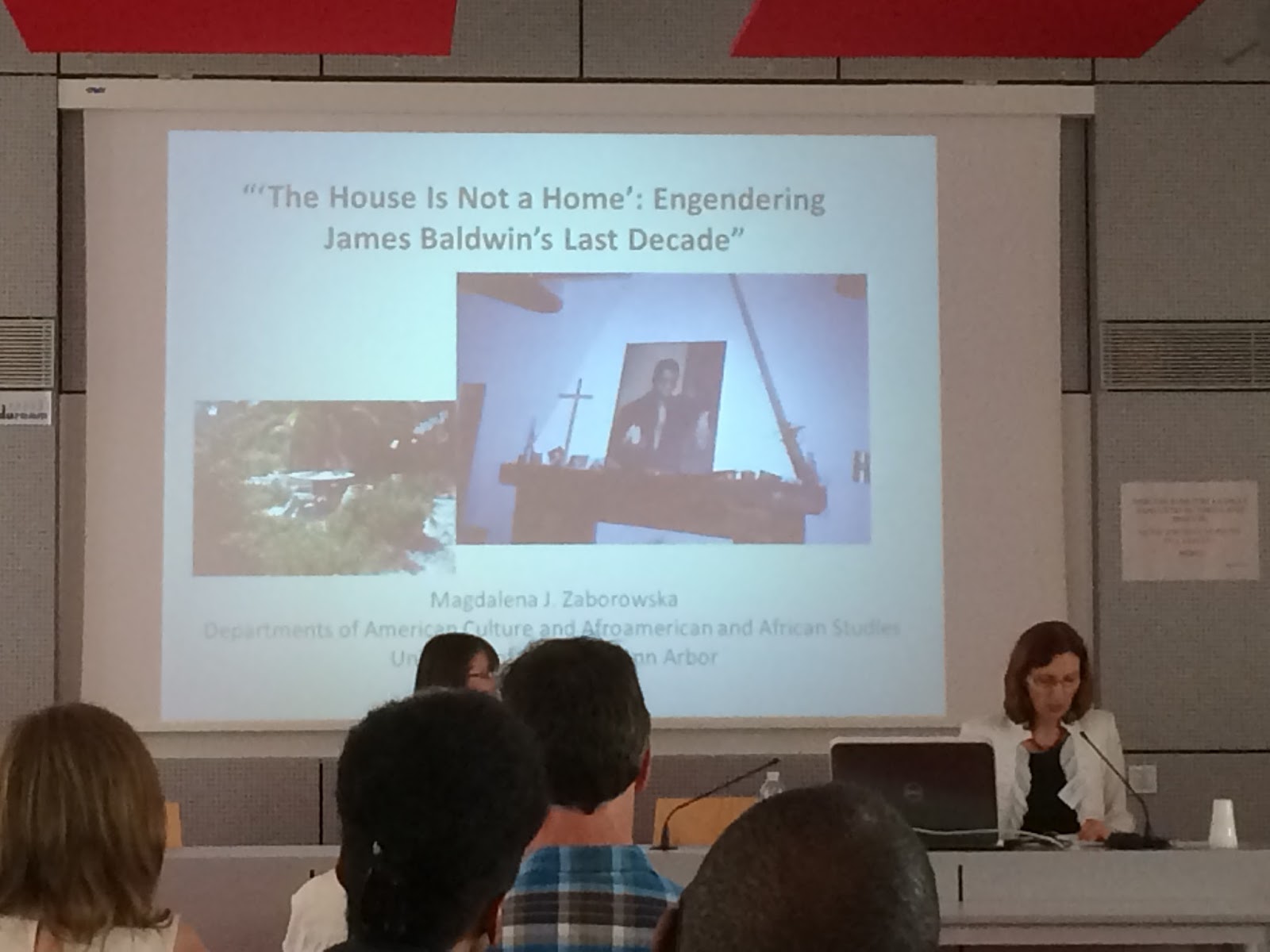

James Baldwin's

Go Tell It On the Mountain. I've been following Als's work avidly for some time, both his journalism in the

The New Yorker and other venues (

The Village Voice many moons ago), and his strange, compelling study,

The Women (which I hope to teach one of these days). Much in line with his journalism, Als's talk, which included a brief fictional addendum that imagined Baldwin at cocktail parties, was as much about himself and his attitudes towards Baldwin, writing, Black folks, and the vexed relationship between artmaking and socialization as it was about Baldwin. He suggested that Baldwin was torn between two poles: the desire to be alone, and make his art (which a writer must do), and the desire to be social, loved, and, extending from this, famous, and he related this to the quandary many writers face, which is that they expect to be loved for their work, with the work become a kind of prosthesis for the ultimately unloved self. Fame increases the attention and phantasm of love, but doesn't in the end constitute it, and for Baldwin, he ended up becoming something he said he wouldn't but also was unable to achieve the level of accomplishment he aspired to in the genre that was most important to him, prose fiction, or the form, the novel.

Als began by describing how he thought of Baldwin as he watched a news report about the horrific immolation that

Betty Shabazz suffered at the hands of her grandson, her husband's namesake,

Malcolm Shabazz, and he rather controversially linked this moment to Baldwin by stating that the Black gay boy is regarded at times as a little Malcolm Shabazz, setting the Black house aflame with our difference (well, perhaps not so controversial, as our own Senator

Barack Obama has decided to prove); he went on to add a bit about Black gay boys also going after a white Jesus of our own, which was even more problematic, though I think I grasped what he was saying with this as he later discussed

Eldridge Cleaver's infamous homophobic attack on Baldwin's work as representing a "racial death wish" and, echoing Baraka's denunciation of the Black middle class in many of his works of the late 1960s, as "the apotheosis" of a "Black bourgeoisie," separated from their culture. Further ironizing this reference, Als talked about

Norman Mailer's dismissal of Baldwin's "perfumed wit," or to put it more broadly, his "high faggot style," which Als noted that he loved. Baldwin, however, got his revenge in an essay, "The Black Boy Looks at the White Boy" (title?). From here Als explored personal thoughts about his own relationship with Baldwin, and had already noted that Baldwin was born out of wedlock, as was he (Also was also, I think I heard him say, an adoptee), and was, ina basic sense, an alien in his own family. Despite these parallels, Als felt he wanted to dislike Baldwin more, and I picked up a strong sense of what, of all people, Harold Bloom described as an "agony of influence," with Baldwin not merely an ancestor and predecessor, but the source of an ongoing "agon" for Als. It is true that every Black gay male writer writes under the star (in all senses of that word) of Baldwin (and

Hughes, and

Nugent, and

Cullen, etc.), but for Als, it seems, the relationship transcends the historical and is continually contestory. (Personally I've never wanted to "dislike" Baldwin at all, and when I was younger I reverenced him; I much more aware of his literary failings and his personal imperfections, but he remains for me, as for so many writers, a towering and essential figure. He was, I should add, the spark that light the fire that became the

Dark Room Writers Collective, among other things, though his influence was also central to the

Other Countries and related writing groups of the 1980s. I also have never been the sort to flee the other Black gay person--or Black person, for that matter--in the room, but that's for another discussion.)

Also tied up his talk by noting that Baldwin's unpublished letters were one of the great unknown masterpieces of American literature. Unfortunately, his family won't allow them to be published because they shed a negative light on their father, who was not his, which led to the rhetorical bow: "even a bastard can be reclaimed by his family." The house in flames, but the arsonist redeemed. I wasn't too sure about this bit, but overall it was an engaging talk--underlined, as was necessary, but Als's

performance of it, as interesting and necessary to the lecture as the text itself--and one of the highlights, at least to me, of the fall. (It was also delicious to hear Als invoke his good friend, another Black gay male writer,

Darryl Pinckney, as he

read Baldwin's

Just Above My Head, which

Robert Reid-Pharr successfully defends and explicates in his new study

Once You Go Black, and which my university colleague Nick Davis also defended in a question he posed to Als. I specifically asked about Black gay male literary geneology, activism, and the place of writing, both in terms of Als and other writers--from Sterling Houston to young Black gay writers of today--and got a sort-of answer; it's a topic that my former colleague

Dwight McBride and

Devin Carbado broach in their anthology of several years ago, and which still calls out for considerably more treatment.) After the event I got to meet Als and kee-kee with him for a hot second, which was a real treat, but I also got to praise him in person for what I still consider to be one of the best and more outrageous journalistic pieces to appear in a mainstream US publication, his profile of

André Leon Talley. As soon as I mentioned it, he knew I had picked up the underlying frequencies in it completely. It will, he says, be in a book that's on its way. I can say with utter sincerity that I can hardly wait to read it.

***

On Thursday I gave a poetry reading at

Temple University under the auspices of their Creative Writing program, directed by

Samuel R. Delany; poet and scholar

Rachel Blau DuPlessis (and later, her husband Bob) was my gracious host. It was the first time I'd been to Philadelphia since the MLA Conference a few winters ago, and the first time I'd been to Temple, I think, since my cousin graduated from the Tyler School of Art. (Though my flight from Chicago was delayed an hour and the SEPTA train I was supposed to take broke down, leading to an hour-long wait, I still had a ball.) I read with a talented graduate student,

Emily Skaja, and it was a fun reading on so many levels; Chip introduced it, Rachel's students were there, one of my former students from the university brought his wife, and poet and publisher

Sueyeun Juliette Lee, now living in Philadelphia and doing her Ph.D. at Temple, was also present. Oh, and the audience was pretty full--for poetry, by an unknown quantity, on a Thursday! Thanks again to Rachel, Chip, Emily, and everyone else to who came out, and here are two pics over the Schuylkill (the second by Rachel--thanks!); Philadelphia's a city that I've always liked visiting quite a bit, and I look forward to going back there again in the future.

It's been such a busy week a barely know where to begin. But I'll start with Hilton Als's (at right, in a horrible cellphone photo) provocative talk, "The Exile," which was part of this year's One Book One Northwestern series, focusing on James Baldwin's Go Tell It On the Mountain. I've been following Als's work avidly for some time, both his journalism in the The New Yorker and other venues (The Village Voice many moons ago), and his strange, compelling study, The Women (which I hope to teach one of these days). Much in line with his journalism, Als's talk, which included a brief fictional addendum that imagined Baldwin at cocktail parties, was as much about himself and his attitudes towards Baldwin, writing, Black folks, and the vexed relationship between artmaking and socialization as it was about Baldwin. He suggested that Baldwin was torn between two poles: the desire to be alone, and make his art (which a writer must do), and the desire to be social, loved, and, extending from this, famous, and he related this to the quandary many writers face, which is that they expect to be loved for their work, with the work become a kind of prosthesis for the ultimately unloved self. Fame increases the attention and phantasm of love, but doesn't in the end constitute it, and for Baldwin, he ended up becoming something he said he wouldn't but also was unable to achieve the level of accomplishment he aspired to in the genre that was most important to him, prose fiction, or the form, the novel.

It's been such a busy week a barely know where to begin. But I'll start with Hilton Als's (at right, in a horrible cellphone photo) provocative talk, "The Exile," which was part of this year's One Book One Northwestern series, focusing on James Baldwin's Go Tell It On the Mountain. I've been following Als's work avidly for some time, both his journalism in the The New Yorker and other venues (The Village Voice many moons ago), and his strange, compelling study, The Women (which I hope to teach one of these days). Much in line with his journalism, Als's talk, which included a brief fictional addendum that imagined Baldwin at cocktail parties, was as much about himself and his attitudes towards Baldwin, writing, Black folks, and the vexed relationship between artmaking and socialization as it was about Baldwin. He suggested that Baldwin was torn between two poles: the desire to be alone, and make his art (which a writer must do), and the desire to be social, loved, and, extending from this, famous, and he related this to the quandary many writers face, which is that they expect to be loved for their work, with the work become a kind of prosthesis for the ultimately unloved self. Fame increases the attention and phantasm of love, but doesn't in the end constitute it, and for Baldwin, he ended up becoming something he said he wouldn't but also was unable to achieve the level of accomplishment he aspired to in the genre that was most important to him, prose fiction, or the form, the novel.

Punks by John Keene

Preorder your copy today! (Out in December 2021!)

Punks by John Keene

Preorder your copy today! (Out in December 2021!)

Counternarratives by John Keene (UK Edition)

Order your copy today!

Counternarratives by John Keene (UK Edition)

Order your copy today!

Letters from a Seducer by Hilda Hilst, translated by John Keene, with an introduction by Bruno Carvalho

Get your copy today!

Letters from a Seducer by Hilda Hilst, translated by John Keene, with an introduction by Bruno Carvalho

Get your copy today!

The Obscene Madame D by Hilda Hilst, translated collaboratively by Nathanaël and Rachel Gontijo Araújo, with an introduction by John Keene

Get your copy today!

The Obscene Madame D by Hilda Hilst, translated collaboratively by Nathanaël and Rachel Gontijo Araújo, with an introduction by John Keene

Get your copy today!