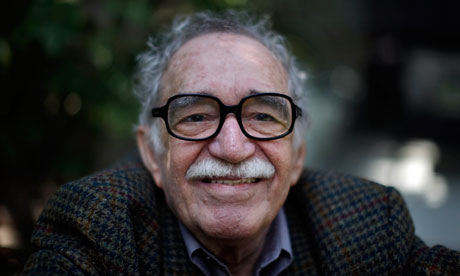

First came the email from Reggie H., then I saw the report on Raw Story followed by one on the Guardian's site stating that Gabriel García Márquez, the Colombian author and journalist who received the 1982 Nobel Prize in Literature, is now, according to his brother Jaime García Márquez, suffering from dementia exacerbated by treatment for lymphoma that was first diagnosed in 1999.

García Márquez is best known for his superlative 1967 novel One Hundred Years of Solitude (Cien años de soledad), the most acclaimed and widely read, and perhaps most paradigmatic in terms of the genre of "magical realism," of all the Latin American "Boom" novels of the 1960s and 1970s. His subsequent novels such as Love In the Time of Cholera (El amor en los tiempos del colera, 1985) and The General in His Labyrinth (El general en su laberinto, 1989); short story collections including No One Writes to the Colonel (El coronel no tiene quien le escriba, 1961) and Leaf Storm and Other Stories (La hojarasca, 1961, his very first published book); and his journalistic nonfiction volumes like Chronicle of a Death Foretold (Cronica de una muerte anunciada, 1981) and Clandestine in Chile: The Adventures of Miguel Littín (La aventura de Miguel Littín, clandestino en Chile, 1986) all have only cemented his fame. (One of my favorite of his novels is one of his most experimental and

forbidding, consisting as it does one long block of paragraph-less

prose, The Autumn of the Patriarch [El otoño del patriarca], 1975.)

García Márquez's work has influenced innumerable writers, including his peers, across Latin America and the globe. Throughout his career, he has been an outspoken man of the political Left, an indefatigable commentator on contemporary events, and a larger-than-life figure in the world of global letters, sometimes brawling in print, sometimes with fists (cf. Mario Vargas Llosa). He published his most recent book in 2004, Memory of My Melancholy Whores (Memoria de mis putas tristes), and the Raw Story article points out that it received mixed reviews, but then so did some of his later books. Jaime García Márquez told his student audience in Cartagena, Colombia that his brother, now 85 years old, "has problems with his memory" and can no longer write. The chemo checked the lymphatic cancer, but, as has been noted sometimes with other cancer patients, damaged the writer's brain. He added, "Sometimes I cry because I feel like I'm losing him." García Márquez's cessation of his writing practice is a loss for literature, but what he has produced will stand forever as an extraordinary testament; his masterpiece by itself will certainly endure, as will many of his other works, especially the short fiction and novels. As for the writer himself, I hope that his suffering is minimal, and that he spends his remaining days in Mexico, where he has lived for decades, in comfort, with loved ones.

***

I have refrained from posting extensively on the New York Public Library's plans to radically redesign its landmark Research Branch building, at Bryant Park, into a lending library with expanded Net access infrastructure and a café (or several), as well as with an attenuated staff, moving a large portion of the stacks now within the building and below the park to an offsite facility near Princeton, New Jersey, while also closing two branches, one the well-patronized but shabby Mid-Manhattan Library right across the street, the other the science and technology library that shares a building with the City University of New York's Graduate Center, in the old B. Altman Building near 34th Street, because the NYPL's Research Branch and its collections are among the treasures I love the most in New York City, and because whenever I begin to post on the topic I find my blood pressure starting to rise.

I am not the only one: the proposed changes have provoked a furor among researchers, writers, and everyday New Yorkers, and many are not rolling over and keeping quiet, despite the vast amounts of wealth those seeking the changes wield. What the NYPL is facing, however, is not an isolated case; all over the country, libraries are facing reduced funding and privatization, just as public institutions in general are. It is hardly news to say the commons, and the common good, funded by all for all, is increasingly under threat in favor of what is of interest, however narrow and poorly thought out, to those at the very top of the economic pile. In the case of the NYPL, New York City and surrounding areas have one of the great libraries in the world, rivaled in its breadth and depth in the United States by only a few other institutions, including the libraries at Harvard University and the Library of Congress. And the NYPL is public, so anyone can come into the Research Branch, apply for a card to read and review books and, once the process is underway, have those books in hand, be they contemporary novels, an early edition of Benjamin Franklin's diary, rare architectural monographs, obscure early 20th century American newspapers in Chinese or Russian or Yiddish, and so forth.

This aspect of the library's mission is apparently not so important to the people pushing to have the stacks gutted and the new infrastucture installed. I think immediately of the assault--because it has far surpassed indifference--on the humanities and social sciences by people not just on the political right but even among "left"-leaning technocrats, none of whom seem to recognize the ancient and ongiongbusiness-driven model of operation poses. As I noted, the brouhaha the proposed changes has provoked keeps growing. As the Guardian's Jason Farago says in his article "What lies behind the battle over the New York Public Library, "Hundreds of writers, from Peter Carey to Mario Vargas Llosa, have gone on record against the plan. An exhaustive exposé in the literary magazine n+1 raised the temperature, and the current issue of the New York Review of Books contains page after page of tetchy point v counterpoint. Whatever the fate of our library, a lot of people are going to be very angry when this is all over."

They will be, we will be. The we being the majority (call us the 99%) who treasure the library as it has been and is and could continue to be, with adequate funding and support, or, if as was the case when the global financial crisis caused by the 1% led to a temporary halt in these dreadful plans, the they could be those who want to tear the library's innards out to put in...who knows what, but whatever it is, it will most certainly become antiquated by the time they are heading to their graves, or cryobanks, or wherever obscene rich people will be going in the future. I think of the rapid changes in technology that have occurred even since I began writing this blog in 2005, and how I didn't foresee an app version of this site nor can I envision what forms it might take down the road.

What the future holds for digitization, for access to digitized works, for standardization of digital platforms, for libraries in general, I cannot say, nor can people whose daily livelihood is to consider the answer to these questions. Most certainly an affordable, particularly a free, universal digital online library would benefit all humankind who had the ability the access it, but physical public libraries themselves would still play important roles all across the globe. Yet in the NYPL, in its marble halls, in its splendiferous Main Reading Room, in its other special rooms and collections, and I can attest to this fact having spent a great deal of time in it, there are books from 2005, from 1905, from 1805, from 1605, from much further back, that I have held, looked through, taken notes from, read and studied carefully, with ease and pleasure.

Will any technology for reading devised today last as long as these texts? We don't know. But the NYPL's ample collection makes a case for what has perdured and continues to do so. If only the NYPL's trustees and its current CEO realized this and proceeded accordingly.

***

This is serious business not just for Berkeley's students, faculty and staff, but for the state of California and for knowledge creation in general. It is, unfortuately, of a piece with similar shifts all over; I am going to avoid hyperbole, but to put it simply, all these changes amount to flushing ourselves down the drain. We can still stop it, but we have got to get past complacency, fear, and everything else that is entropically leading us towards our own self-cancellation. We have to, and we can.

|

| Gabriel García Márquez (Photograph: Miguel Tovar/AP) |

García Márquez's work has influenced innumerable writers, including his peers, across Latin America and the globe. Throughout his career, he has been an outspoken man of the political Left, an indefatigable commentator on contemporary events, and a larger-than-life figure in the world of global letters, sometimes brawling in print, sometimes with fists (cf. Mario Vargas Llosa). He published his most recent book in 2004, Memory of My Melancholy Whores (Memoria de mis putas tristes), and the Raw Story article points out that it received mixed reviews, but then so did some of his later books. Jaime García Márquez told his student audience in Cartagena, Colombia that his brother, now 85 years old, "has problems with his memory" and can no longer write. The chemo checked the lymphatic cancer, but, as has been noted sometimes with other cancer patients, damaged the writer's brain. He added, "Sometimes I cry because I feel like I'm losing him." García Márquez's cessation of his writing practice is a loss for literature, but what he has produced will stand forever as an extraordinary testament; his masterpiece by itself will certainly endure, as will many of his other works, especially the short fiction and novels. As for the writer himself, I hope that his suffering is minimal, and that he spends his remaining days in Mexico, where he has lived for decades, in comfort, with loved ones.

***

I have refrained from posting extensively on the New York Public Library's plans to radically redesign its landmark Research Branch building, at Bryant Park, into a lending library with expanded Net access infrastructure and a café (or several), as well as with an attenuated staff, moving a large portion of the stacks now within the building and below the park to an offsite facility near Princeton, New Jersey, while also closing two branches, one the well-patronized but shabby Mid-Manhattan Library right across the street, the other the science and technology library that shares a building with the City University of New York's Graduate Center, in the old B. Altman Building near 34th Street, because the NYPL's Research Branch and its collections are among the treasures I love the most in New York City, and because whenever I begin to post on the topic I find my blood pressure starting to rise.

|

| An 19th map of Boston and its environs (collection of NYPL) |

This aspect of the library's mission is apparently not so important to the people pushing to have the stacks gutted and the new infrastucture installed. I think immediately of the assault--because it has far surpassed indifference--on the humanities and social sciences by people not just on the political right but even among "left"-leaning technocrats, none of whom seem to recognize the ancient and ongiongbusiness-driven model of operation poses. As I noted, the brouhaha the proposed changes has provoked keeps growing. As the Guardian's Jason Farago says in his article "What lies behind the battle over the New York Public Library, "Hundreds of writers, from Peter Carey to Mario Vargas Llosa, have gone on record against the plan. An exhaustive exposé in the literary magazine n+1 raised the temperature, and the current issue of the New York Review of Books contains page after page of tetchy point v counterpoint. Whatever the fate of our library, a lot of people are going to be very angry when this is all over."

They will be, we will be. The we being the majority (call us the 99%) who treasure the library as it has been and is and could continue to be, with adequate funding and support, or, if as was the case when the global financial crisis caused by the 1% led to a temporary halt in these dreadful plans, the they could be those who want to tear the library's innards out to put in...who knows what, but whatever it is, it will most certainly become antiquated by the time they are heading to their graves, or cryobanks, or wherever obscene rich people will be going in the future. I think of the rapid changes in technology that have occurred even since I began writing this blog in 2005, and how I didn't foresee an app version of this site nor can I envision what forms it might take down the road.

What the future holds for digitization, for access to digitized works, for standardization of digital platforms, for libraries in general, I cannot say, nor can people whose daily livelihood is to consider the answer to these questions. Most certainly an affordable, particularly a free, universal digital online library would benefit all humankind who had the ability the access it, but physical public libraries themselves would still play important roles all across the globe. Yet in the NYPL, in its marble halls, in its splendiferous Main Reading Room, in its other special rooms and collections, and I can attest to this fact having spent a great deal of time in it, there are books from 2005, from 1905, from 1805, from 1605, from much further back, that I have held, looked through, taken notes from, read and studied carefully, with ease and pleasure.

Will any technology for reading devised today last as long as these texts? We don't know. But the NYPL's ample collection makes a case for what has perdured and continues to do so. If only the NYPL's trustees and its current CEO realized this and proceeded accordingly.

***

Leonard expected to announce the libraries' fate in July. Instead, the faculty objected to being told they had just two choices for the wondrous athenaeums: horrible or terrible.There are no first-rate universities in the world without a first-rate library, or, I would add, a first rate public library, at the very least, nearby. A truism by any measure, and closed libraries, or librarian-less libraries, do little good for anyone, including the books and other materials in them, and grimmer outcomes are sure to follow. Instead of shuttering the libraries by 2/3rds vs. nearly 1/2, however, Provost George Breslauer and Chancellor Robert Birgeneau, already the target of Occupy-related protests in the past, will convene a "blue-ribbon panel" to study the issue and recommend options by August (2 weeks ago), to be implemented in December of this year.

"There are no first-rate universities in the world without a first-rate library," 110 faculty members declared in a petition asking the university for an extra year to find other ways of keeping Cal libraries not just afloat, but great.

This is serious business not just for Berkeley's students, faculty and staff, but for the state of California and for knowledge creation in general. It is, unfortuately, of a piece with similar shifts all over; I am going to avoid hyperbole, but to put it simply, all these changes amount to flushing ourselves down the drain. We can still stop it, but we have got to get past complacency, fear, and everything else that is entropically leading us towards our own self-cancellation. We have to, and we can.