"How has the black female body been idealized and misread in visual culture?" And: "How might these tendencies affect black women today?"

|

| Tisa Bryant, Isolde Brielmeier, Deborah Willis, Carla Williams |

These were just two of the many provocative questions posed yesterday at a

Brooklyn Museum of Art panel discussion entitled "The Black Female Body in Art," which took place in conjunction with the museum's superb current exhibit,

Mickalene Thomas: Origin of the Universe. The exhibit, featuring a range of Thomas's (1971-) current work, includes a mural, large scale paintings, smaller mixed-media works, photographs, a room-sized multi-part installation, and a video, and is located in the Morris A. and Meyer Schapiro Wing, on the museum's 4th floor. It runs through January 20, 2012. The panel comprised four distinguished participants, each of whom brought distinctive perspectives to their viewings of and discussions on Thomas's work, and on the broader topic: visual artist, photographer, curator, historian, and NYU professor

Deborah Willis;

Isolde Brielmaier, Chief Curator at

Savannah College of Art and Design (SCAD) and Visiting Assistant Professor of Art at

Vassar;

Carla Williams, coauthor of

The Black Female Body: A Photographic History; and my very good friend, writer, art and cultural critic and CalArts professor

Tisa Bryant.

The conversation, which ran for about 2 hours, somewhat skirted the very open-ended questions I noted above, yet did provide insightful context for and readings of Mickalene Thomas's show, and of topics and themes related to and deriving out of it. One of the issues the panel spoke about involved Thomas's revisioning and reappropriation of imagery from the European art historical tradition. The very title of her show, "The Origin of the Universe," derives from

Gustave Courbet's controversial 1866 painting of a nude, head-and-limb-obscured white woman's genitalia, "L'origine du monde," though as Tisa and other panelists queried, what happens when the artwork and the gaze implicit in it is a woman's, a lesbian's, a black woman's, a black lesbian's (and Thomas is a black lesbian) how does that resituate the image, as well as its relation to Courbet's image? (No one noted that Courbet was a committed ideological and political leader of the French avant-garde, and how that underpinned the vision, gaze and gestures implicit in his work, including this one.) Moreover, Tisa pointed out the metonymic resonances in Thomas work, among them black physicality, sensuality, reproductive agency and power, and an invocation of Lucy/Dinknesh, the first human mother/female ancestor. (Other figures Thomas riffs on, directly in terms of images and styles, include

Edouard Manet, Pablo Picasso, and

David Hockney, though I also saw a bit of

Richard Diebenkorn, the Cubists, and

Romare Bearden in her collagistic compositions.)

|

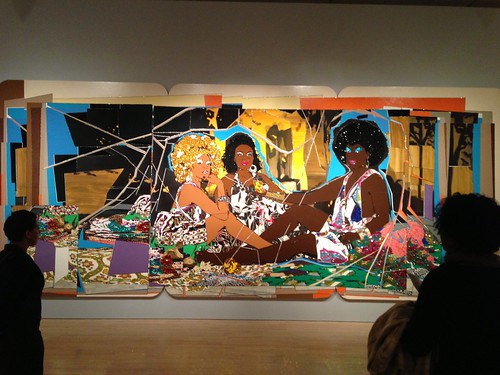

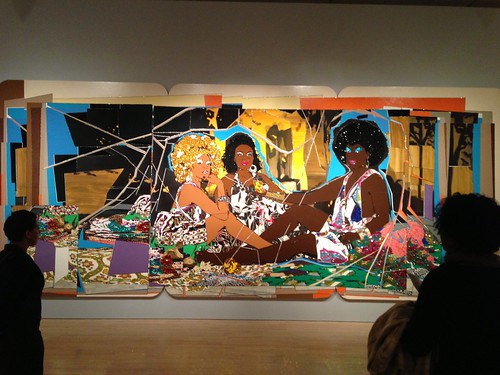

Mickalene Thomas's "“Le Dejeuner sur l’herbe: Les Trois Femmes Noires, Fractured” (2011),

a direct riff on Edouard Manet's "Le Dejeuner sur l'herbe" |

Some other topics I'm still thinking about include Carla Williams's point about the specifics of Thomas's technique and images, and how, despite the artist's direct engagement with the Euro-American (male) artistic past, one could come to and connect with them without "the history of [Euro-American] art," in part because of their rich, bedazzled surfaces, their inviting and provocative imagery, and the personal histories a viewer, especially a black female viewer, might bring. (I thought as well of

Kehinde Wiley, Thomas's contemporary, and his use and appropriation of Renaissance iconography, as well as of predecessors like

Robert Colescott and

Bob Thompson, just to name a few.) For Tisa, the "bling" of the rhinestones--one of the most arresting aspects of Thomas's work, from a distance and up close--brought to mind associations such as the celestial, cosmology, stars and the star system (of mass culture, the art world, etc.), high and low culture, the earthly and the heavenly. "What shines?" she asked aloud, much as the paintings ask us as we look at them. Mouths, eyes and eyelids, sometimes jewelry, areola, fleshly contours, pubic hair and genitalia: what happens when Thomas focuses

our gaze on these aspects of her paintings? Where is the feminine, the queer gaze, and how is she activating it? (My question.)

The topic of black woman's gazes, and black women looking at, seeing, and painting/creating artwork about and for each other, arose several times, including when Deborah Willis asked Tisa specifically about the "diaristic" aspect of the work. Isolde Brielmeier had just noted the "multiple directionality of the gaze," echoing Thomas's own comments, the many "points of entry," the queerness of looking. For Tisa, in the installations was where "subjectivity was most palpable." Carla Williams added that Thomas was one of only a few very well-known and high profile contemporary out black queer female artists, which made even more significant the ways in which she was changing "iconography." I thought about this and about what it means for a black queer woman, especially in an art world that continues to be dominated by white male artists, and which primarily has elevated black male (straight and queer) artists while overlooking many black women, to portray one's mother, one's female friends, one's female lovers, as subjects and objects of love, desire, fantasy, beauty--and manage to shift viewer's expectations, while also not losing your own focus. This issue of looking led Tisa to note the presence of mirrors in Thomas's work--calling to mind Oshun, among others--and the concept of women, regular women, as sources of inspiration, as "muses," to use Willis term and an idea long known to male artists. As Tisa asked, "Who do

we look at?" In Thomas's work, "reverb(erations)"--reappropriations, repurposings, revisionings--she answered, are taking place.

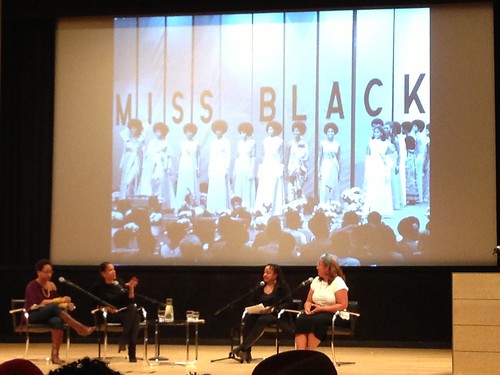

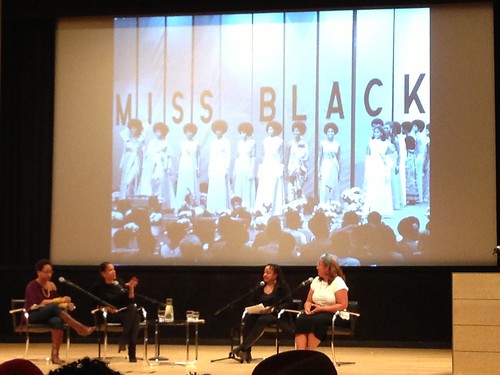

|

The panelists before one of the many evocative images

that accompanied their conversation |

No comments:

Post a Comment