Alexander Kluge, Germany's living avatar of analytical fiction (and a cinematic pioneer in the l950s and 60s), and Gerhard Richter, one of its most important living visual artists, have collaborated on a book entitled December, which Seagull Books, distributed by the University of Chicago Press, published early last year in an English translation. (Seagull posted a pre-publication interview with Kluge in December 2011.)

There are few fiction writers who can pack as much critical thought into condensed, vivid narration as Kluge, and in December it appears he is still working at at the level of adamantine economy he displayed with prior books such as The Devil's Blind Spot (New Directions, 2004) and Cinema Stories (New Directions, 2007). The 80-year-old author's 39 calendar-based narratives here, as in prior books dating back to the 1960s, draw from German, European and global histories as well as from his lively imagination, and sometimes run no longer than a page or two, in concert with Richter's 39 beautiful, enigmatic photographs of wintry landscapes.

The Decembers in these stories, however, bear little of the holiday cheer we associate with the winter holidays or the conclusion of the calendar year. Instead, one story--or prose poem, so brief and clipped is its unfolding--concerns German children collecting scrap metal in 1941. What is not said--the fascist state, brutal war, the Holocaust--looms behind this and other narratives, as it does behind the tranquil but ominous images of nature. A few of the texts present in fictional form realist flashes of Kluge's life; born in 1932 in Halberstadt, in what is now the German state of Saxon-Anhalt (formerly part of East Germany), he likely would have experienced circumstances not unlike these. Most, however, transmit the theoretical and emotional clarity that Kluge's work so often offers, whether he's writing about the near death in 1931 of Adolf Hitler or an obscure monk whose sense of time upends our own sense of temporality. Kluge's prose pieces always come pierced, as Rilke might have written, with rays of wisdom and feeling, usually through metaphors and aphorisms, that most other writers would take sentences to achieve.

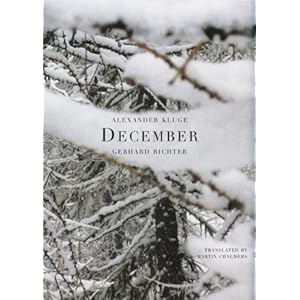

Last month, The New York Review of Books published three Kluge excerpts, alongside three Richter images. I found myself rereading the Kluge pieces several times despite their brevity, and studying the Richter photographs, which grew more ominous with each view. You can read the pieces at the NYRB link above. (You can download some of his movies here.) Below is one of the photographs. If you were to compose a short prose piece for December to accompany this image, what would it be?

There are few fiction writers who can pack as much critical thought into condensed, vivid narration as Kluge, and in December it appears he is still working at at the level of adamantine economy he displayed with prior books such as The Devil's Blind Spot (New Directions, 2004) and Cinema Stories (New Directions, 2007). The 80-year-old author's 39 calendar-based narratives here, as in prior books dating back to the 1960s, draw from German, European and global histories as well as from his lively imagination, and sometimes run no longer than a page or two, in concert with Richter's 39 beautiful, enigmatic photographs of wintry landscapes.

The Decembers in these stories, however, bear little of the holiday cheer we associate with the winter holidays or the conclusion of the calendar year. Instead, one story--or prose poem, so brief and clipped is its unfolding--concerns German children collecting scrap metal in 1941. What is not said--the fascist state, brutal war, the Holocaust--looms behind this and other narratives, as it does behind the tranquil but ominous images of nature. A few of the texts present in fictional form realist flashes of Kluge's life; born in 1932 in Halberstadt, in what is now the German state of Saxon-Anhalt (formerly part of East Germany), he likely would have experienced circumstances not unlike these. Most, however, transmit the theoretical and emotional clarity that Kluge's work so often offers, whether he's writing about the near death in 1931 of Adolf Hitler or an obscure monk whose sense of time upends our own sense of temporality. Kluge's prose pieces always come pierced, as Rilke might have written, with rays of wisdom and feeling, usually through metaphors and aphorisms, that most other writers would take sentences to achieve.

Last month, The New York Review of Books published three Kluge excerpts, alongside three Richter images. I found myself rereading the Kluge pieces several times despite their brevity, and studying the Richter photographs, which grew more ominous with each view. You can read the pieces at the NYRB link above. (You can download some of his movies here.) Below is one of the photographs. If you were to compose a short prose piece for December to accompany this image, what would it be?

|

| © Gerhard Richter |

No comments:

Post a Comment