Thane Rosenbaum, in his Forward essay, "Yeah, But the Book Is Better," poses some interesting questions concerning the relationship between works of fiction, primarily novels, and their film versions. What provoked his inquiry in this short essay was that his 1999 novel, Second Hand Smoke (which I've never read), was being turned into an independent film, and Rosenbaum was asked to adapt it into screenplay form. He notes that the process proved very instructive, and the essay offers some of his conclusions about how prose fiction differs from its cinematic versions, and why translations of certain texts, such as Kafka's brilliant stories and novels, don't and probably can't work.

Thane Rosenbaum, in his Forward essay, "Yeah, But the Book Is Better," poses some interesting questions concerning the relationship between works of fiction, primarily novels, and their film versions. What provoked his inquiry in this short essay was that his 1999 novel, Second Hand Smoke (which I've never read), was being turned into an independent film, and Rosenbaum was asked to adapt it into screenplay form. He notes that the process proved very instructive, and the essay offers some of his conclusions about how prose fiction differs from its cinematic versions, and why translations of certain texts, such as Kafka's brilliant stories and novels, don't and probably can't work.(For years I thought and repeated that Toni Morrison's dense, lyrical novels would prove untranslatable into film under any circumstances, but Oprah Winfrey dared to do so anyways with Beloved, and I now think that the right director--someone with a truly idiosyncratic style, perhaps on the order of a Michelangelo Antonioni or Julie Dash, who'd be willing to radically adapt a work like Jazz or Love--could create a marvelous piece out of one of her texts. Still, there are fiction authors like Wilson Harris, Julian Ríos, Juan Goytisolo, or Leslie Scalapino or M. Nourbese Philip works in general and individually still strike me as untranslatable, in part because of their texts' sheer conceptual and linguistic density and because of the nature of their narratives/narration.)

Rosenbaum isn't the first person to explore this topic, of course; literary, film and narrative theorists, aestheticians, filmmakers, fiction writers, journalists and others all have explored the relationship between prose fiction and film at various points. One of the most famous essays that immediately comes to mind is Seymour Chatman's Critical Inquiry essay, "What Novels Can Do That Films Can't (and Vice Versa)." It later appeared in the still useful volume of Critical Inquiry essays and responses, by the likes of Hayden White, Jacques Derrida, Paul Ricoeur, and Barbara Herrnstein Smith, that W. J. T. Mitchell edited in 1981, On Narrative (Univ. of Chicago Press). Chatman's short essay, which draws from his larger, invaluable study Story and Discourse: Narrative Structure in Fiction and Film (Cornell University Press, 1980), analyzes the relationship between story and discourse, pointing out the differing temporalities in prose and cinema, the use of visual imagery, which is absolutely necessary in film but not in prose, the role of prose texture, and so on. In the essay (and the book), Chatman draws examples from classic European and American films, which I was unfamiliar with (and which I'd assume most contemporary readers would be), but you could update his examples, I think, with more recent and apt examples and still make similar points. Rosenbaum captures a bit of Chatman's article, but he's more categorical in his statements and misses some of the nuance.

Rosenbaum says:

With a novel, the author forms an implicit partnership with his audience. He provides the story and its voice, but the reader adds the visuals. The power of a novel's description is often tempered by sketchy details. Much is left out in order to leave something to the imagination. The reader is free to conjure the characters in his own way, to picture how they look, because the mind's eye has a way of assembling an image that is quite different from how a character might appear on screen. In the end, the novelist surrenders his book to his readers. Thereafter it becomes theirs, and his proprietary interest ceases.He goes on to say that films are more "controlled" by the director (and I'd add the film editor, as well as the studio), and that the camera controls the point of view.

This is true, to some degree. But I would add that the comparison isn't that simple or dichotomous. Some authors--especially some of the greatest ones--create indelible portraits of characters that, though never accompanied by a visual image, are nearly as strong and prevent us from ever yielding to the cinematic version if we read the novel first (can any filmic Holden Caulfield or Jay Gatsby compare to the novelistic version if you've read the respective novels first?), or engrave on our consciousness a voice that echoes for years in our heads that the film version creates only a vague or discordant echo of, or, in other cases, leave us afloat in language itself, with few images and only a vague "contract" of sorts, while still carefully guiding our mental activity and emotional registers.

He also says:

[In a novel], not everything needs to be resolved, not every loose end must be tied up for the novel to be satisfying. Ambiguity is tolerated much more readily; the impulse toward linearity — the beginning, middle and end of a story — is almost nonexistent in modern fiction.

This might have been true of Modernist fiction, or even much post-Modernist fiction, but I can think of at least twenty major novels of the last 10 years--by the likes of Jeffrey Eugenides, Jonathan Franzen, Edwidge Danticat, Danzy Senna, Margaret Atwood, Philip Roth, Jonathan Lethem, Patricia Powell, Chang-Rae Lee, Jhumpa Lahiri, Colson Whitehead, etc.--that all hew to the "impulse to linearity," and all have received critical acclaim and achieved commercial success. (In fact, for an American novel to be commercially viable nowadays, it almost has to be linear, or if non-linear, then in a fashion that is ultimately propulsive towards a narrative climax (and perhaps denouement)). At the same time, feature films are capable of tremendous ambiguity, even when rich with images, and which despite the camera's guiding "point of view" still leave ample room for and power in the viewer's perspective. Above I mentioned Antonioni; a while back I wrote a review of his masterpiece L'Eclisse (1962), which really has no plot at all, and is so ambiguous as to force the viewer to create meaning in the viewing. Antonioni's deft handling of structure, imagery, editing, as well as the acting, which is literally breathtaking at points, all guide our sense of perspective, and yet the viewer must ultimately assemble the movie, create coherence. This is especially true given the final scene, which approximates a poetic epilogue whose relation to the film is, as philosopher Paul Ricoeur suggests in his essay "Narrative Time," purely associative--and very much like the kind of digressive passages or interludes in a novel that Rosenbaum describes at another point in his essay.

Another director who falls into this category is Wong Kar-Wai; if you want a great deal of ambiguity--almost complete ambiguity--and eschew plot or take a very broad view of what narrative is, then his recent, remarkable film 2046 would have to be exemplary (I actually like the plangently desire-ridden In the Mood for Love a bit more). It is almost all imagery, structure, mood, music, acting--but again, also so ambiguous and open as to leave the construction of any set meaning, as we usually think of it, to the viewer.

Two things that I would add are first that ambiguity and cinematic lyricism need not preclude plot and vice versa; a very good example of a feature film director whose work melds the two is David Lynch. I can recall going to see Blue Velvet (1986) and being astonished to the point of enthrallment; there is a discernible plot in that film, but the point really is something else, as in most of Lynch's films, including the superb Mulholland Drive (2001). The point is the ambiguity of the assemblage, to a great degree, and the irony produced by the act and process of the cinematic narration. Narrative binds everything together and the oulines of the plot initially bid to explain the strange and perverse truths of the story, but the real truth is that in Blue Velvet we're never really sure whose ear Kyle MacLachlan finds, or what exactly is going on with Dennis Hopper, Isabella Rossellini, Dean Stockwell, or the rest of this bizarre underworld.

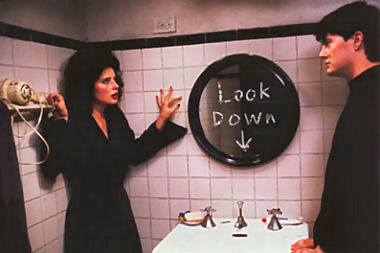

Two things that I would add are first that ambiguity and cinematic lyricism need not preclude plot and vice versa; a very good example of a feature film director whose work melds the two is David Lynch. I can recall going to see Blue Velvet (1986) and being astonished to the point of enthrallment; there is a discernible plot in that film, but the point really is something else, as in most of Lynch's films, including the superb Mulholland Drive (2001). The point is the ambiguity of the assemblage, to a great degree, and the irony produced by the act and process of the cinematic narration. Narrative binds everything together and the oulines of the plot initially bid to explain the strange and perverse truths of the story, but the real truth is that in Blue Velvet we're never really sure whose ear Kyle MacLachlan finds, or what exactly is going on with Dennis Hopper, Isabella Rossellini, Dean Stockwell, or the rest of this bizarre underworld.I'd also say that although I would agree to some extent with Rosenbaum's statement that "dark psychological complexity is not particularly well suited to cinema, which is why Fyodor Dostoevsky's novels have not been successfully adapted," there have been some notable films that challenge this notion; for example, Alfred Hitchcock's Suspicion (1941), Shadow of a Doubt (1943), Vertigo (1958) and Psycho (1960), Charles Laughton's The Night of the Hunter (1955, above, at right), Martin Scorsese's Taxi Driver (1976), István Szábo's Mephisto (1981), or Woody Allen's Crimes and Misdemeanors (1989), Lars von Trier's Dogville (2003), anything by Michael Hanneke, etc., all come to mind.

Finally, I continue to believe that filmmakers can make great films out of bad or at least middling novels or short stories more easily than out of great ones. One reason may be that the director feels less fidelity to a weaker text and may seek to improve it filmically. Another may be that the weaker work leaves more options for adaptation. Still another is that the best novels not only bear the strong imprint of their authors, but also display the sort of directorial control--in terms of style, narration, and so on--that Rosenbaum attributes to directors, in addition to those features that are constitutive of prose fictional narration. But, with the right director and work, anything is possible, I think. So when is Lynne Cheney's lesbian-tinged novel Sisters going to hit the big screen?

excellent post, john. with the recent adaptations of the lion, the witch and the wardrobe (which im going to see today...AND, I hear Tilda Swinton is a tour de force as Jadis, The White Witch), i have been wondering about this very subject.

ReplyDeleteIt can be quite difficult to get the essence of a book on film. Much is lost or dropped in favor of "narrative simplicity", etc.

Which is why james baldwin, salman rushdie, most of margaret atwood's novels, toni morrison and samuel delany AND Octavia Butler, just to name a few, have never been adapted for the silver screen or are too difficult to adapt because their respective narrative structures challenge and question the fluidity of a "linear narrative"....

of course, these are authors I think who are IN NEED of being adapted since their works are so timely, so rich, and so very symbolic of the world we live in.

of course, you and I have talked about samuel delany and the book I want to adapt for the silver screen. The other books I want to take a stab at:

The Edible Woman Margaret Atwood (a PERFECT film for Thandie Newton, if you ask me)

Another Country James Baldwin

Kindred Octavia Butler

Haround and The Sea of Stories Salman Rushdie

Tar Baby (SO NEEDED given the black community's long standing obsession with light skin, etc.) Toni Morrison

of course, my lack of time in the day to sit down and write is a major issue...which is one of my new year's resolutions: devoting MORE to my writing projects, etc.

but a good post...oh, i totally thought of you when I saw Haneke's Cache. I'm planning to see it this week and was going to ask if you wanted to see it. But, i forgot you are going back to Chicago soon. But, I will tell you about my thoughts on the film when I see it....

happy new year!

Happy New Year, baby!

ReplyDeleteAs you may or may not remember, the opening of the film verson of Umberto Eco's bestseller begins with a title card, calling itself 'A palimpset of The Name of the Rose.' So it is with all films based on novels (or short fiction). Comparing the two is like comparing apples to apple pie (or in the case of a not so good film, applesauce!)

Because we have the author's voice in our head when we read, we are unreeling the novel in our mind's theater as we move through the book. The more a novel is an event of language rather than plot/what happens next, the more difficult it is to translate to film. Which may be one reason why, say The Maltese Falcon (which uses much of Hammet's dialogue in the book verbatim) is a more successful translation than Beloved. Or more 'middling' novels can become very good movies (Orson Wells' fractured but still glorious Magnificent Ambersons)

And too, one can't approach the source as some kind of Holy Text not to be changed in the transfer from page to screen -- another problem with Beloved perhaps? I agree that someone perhaps more inventive or 'radical' in their interpretation -- for example, the floating world Raoul Ruiz created for his Proust film, Time Regained -- could have created something special with that, but there was such outsized reverence for the book and Morrison that it just wasn't possible to do. ONe can/should honor the original work and most particularly the 'tone' of the book, but its not necessary to be totally faithful.

One example of this is the very good film version of Scott Spencers', Waking the Dead (a novel I love). I shuddered to think what a film of it would turn out to be, but combining a very good screenplay, intelligent direction and some great acting by Billy Crudup and Jennifer Connelly and it turned out quite well.

Having said all that, there are still books that I think would make good movies. One of my choices would be another favorite, Paule Marshall's The Chosen Place, The Timeless People. You're in Chicago, John -- slip a copy to Oprah with a suggestion that she play producer again for me will ya?:)

Much love to you & C-daddy!:)

Ryan, I definitely want to see The Lion, Witch and the Wardrobe both because I loved the story when I was small but also because of my curisoity about how it was adapted, the buzz around Swinton's performance, and a desire to see how far Hollywood went in underlining the Christian undertow of the book. When you see it, please post about it!

ReplyDeleteI think a number of Baldwin's novels could work as films, as could Atwood's The Blind Assassin or Oryx and Crake (Kubrick could have done that one); Morrison and Delany would be much more difficult, I think.

who are IN NEED of being adapted since their works are so timely, so rich, and so very symbolic of the world we live in.

I agree with you about authors who need to be adapted. One whose works would translate well, with the right, fearless director, would be E. Lynn Harris. Another that comes to mind is Jonathan Lethem. Paul Auster's novels could be the template for Lynch film, though I'm not sure they're sexually dark enough. And so on. I like your list, though!

of course, you and I have talked about samuel delany and the book I want to adapt for the silver screen. The other books I want to take a stab at:

Haroun, by the way, became an opera scored by Charles Wuorinen, one of the major avant-garde composers. Some of the reviews praised it fulsomely, while others couldn't hold back their disgust with Wuorinen's 12-tone composition.

Also post about Caché; I'm praying it's playing in Chicago when I get back.

***

Reggie,

Happy New Year to you!

I do barely recall that title card, and in a sense, all adapted works are, to some extent, palimpsests (especially in the sense that the traces remain, though the most faithful ones would metaphorically constitute something much stronger, right?).

I have to say that I don't always have the author's voice--or language--in my head, depending upon the film and book. Doctorow's language in Ragtime was there when I saw the film the second time (since I hadn't read the book when the movie version first appeared), but other works, like The French Lieutenant's Woman, had actually dissipated by the time I saw the film. (Perhaps I was just too young and read Fowles' beautiful, complex novel too quickly.) I agree with you about the degree of the novel being an "event of language" determining its translation, although I also think that some works, like Claude Simon's novels, could very easily translate into highly complex, astonishing pictures--though they would be very different in form when translated. I also think that Beloved was too faithful to the novel and didn't reconceptualize it for the new form, which is essential for great film. It must be RETHOUGHT as film--unless of course it is already written basically as a screenplay in prose, which would be a kind of applesauce, wouldn't it?

I liked Raul Ruiz's version of Proust--he really did try to reconsider how to reamke it so taht it worked cinematically. It still doesn't fully work, but then how could it without becoming something completely else?

I haven't read or seen the Spencer work, so I...

Oops-my flight now is boarding, so let me get on it. I'll write more later...!

Love to you and M-Daddy!!!!

Resumed--so I can't really comment.

ReplyDeleteI agree with you about Paule Marshall. I would discuss her with Oprah if that opportunity opened up, though I don't think it will anytime soon. Marshall's DAUGHTERS seems like a readily translatable book to me. What do you think about that one? I agree that would rather see CHOSEN PLACE, TIMELESS PEOPLE, BROWN GIRL, BROWNSTONE, or PRAISESONG FOR THE WIDOW as movies first.