It is with sorrow that I report the passing of Bernard Hoepffner (1946-2017), the belauded French translator of many Anglophone authors and works, including Mark Twain, James Joyce, Robert Burton, Martin Amis, Edmund White, and Robert Coover, as well as my Counternarratives--his masterpiece of a translation appeared last year. First, the sad, astonishing news: on May 26, French news outlets reported that Hoepffner had disappeared after being swept away by a wave on the Welsh coast, near St. Davids Head, Pembrokeshire, on May 6. (His body was recovered yesterday on Tywyn Beach in North Wales.) With this almost inconceivable event, the world of letters and translation, in France and worldwide, has lost a major, deeply appreciated figure, as a number of his colleagues have readily attested. His varied career before becoming a translator included having restored Asian art in the UK, and a run a farm in the Canary Islands. Once he undertook translation as a career, he ranged widely, never shying away from difficult books, and as the list above suggests, he translated classics as well as newer authors with aplomb. To his family and friends, I send my deepest condolences and prayers.

Aux anges littéraires, and you can find more tributes to his life and work on the page his brother has established for him. I also hope someone will publish those Davenport letters; reading Davenport alone provides a rich education, so I can only imagine how enlightening Davenport and Hoepffner in conversation will be.

***

When I was in my 20s and first encountered the work of Juan Goytisolo (1931-2017), in particular his 1966 novel Marks of Identity (Señas de identidad), it hit me like a meteor. Not only did the story reset my thinking about how you might draw upon autobiography while writing a story that cast far wider imaginative, philosophical, political, and critical nets, but his relentless experimental method of telling it mesmerized me. What I soon learned was that this novel wasn't the then-35 year old Goytisolo's first, but his tenth, and that while he had written his late 1950s and early 1960s novels, which grappled with conditions in Francisco Franco's fascist Spain in a more conventional, social realist style, by the time he published Marks of Identity, he had begun to criticize his native country openly and harshly, and had been living in exile for a decade, in France. He never ceased his critique nor separation from his homeland, despite periodic visits much later; both extended to the end of his life.

Marks of Identity, I was also soon to grasp, was but the first in a trilogy centering on his literary stand-in, Álvaro Mendiola, and the predecessor to what is his most extraordinary and daring novel, Count Julian (La reivindicación del Conde don Julián). Published in 1970, Count Julian remains a landmark in Spanish language, European and global literature, and is one of the most brutal attacks on national tradition written from within that tradition to perhaps ever achieve major fame. In it, Goytisolo lacerates Spain's history by reinvoking and vindicating a figure thought to be one of Spain's greatest traitors, the eponymous Count Julian of Ceuta, who is said to have opened the door to the Moorish conquest. Taking the linguistic experimentation of Marks of Identity even further, but with his irony sharpened like a straight razor, his Count Julian's recitation of Spain's historical crimes woven like the dazzling threads of an exquisite tapestry as he peers through his window at the monstrous home country across the Straits of Gibraltar, Goytisolo holds nothing back. It is a breathtaking work, and won him readers across the literary landscape, though no few fans among Franco's hierarchy or the country's traditional literary world. It is telling that this magisterial, endlessly inventive writer did not win Spain's major literary prize, the Premio Miguel de Cervantes, until three years before his death, in 2014--and never won the Nobel Prize, though his vision, formal, political, spiritual, far outstrips most of the last decade of recipients of that award.

Anti-racist, anti-capitalist, anti-establishment--and ever-willing to speak out: you could characterize the bulk of Goytisolo's work this way. A Barcelona native, from a prominent family, he lost his mother to a fascist bomb as a child. His two brothers, the older Jose Augustín Goytisolo (1928-1999) and the younger Luis Goytisolo (1935-), also wrote, but Juan was the towering figure among them. After arriving in Paris Goytisolo initially worked for Gallimard, and met his future wife, novelist, publisher and screenwriter Monique Lange, soon thereafter, but, as he revealed to her and to his readers in his work, he was gay, and together they built a life that acknowledged this crucial aspect of his existence, which shifted more fully into a new form of living after her death and his move to Morocco, where he lived with two former male partners and their extended families.

As a fiction writer, Goytisolo never looked backwards in terms of his aims to push the limits of the genre or the Spanish language, as books like Juan the Landless (Juan sin tierra, 1975), the third novel in the Mendiola trilogy; Makbara (1980), set in a Muslim graveyard; Landscapes After the Battle (Paisajes después la batalla, 1985), which prefigures Houellebecq's Submission, but in more inventive and anti-Islamophobic way; Quarantine (Cuarantena, 1991), which explores the AIDS pandemic; Marx Family Saga (1999, La saga de los Marx, 1993), a witty novel about the Communist founder and his family; and his final novel, Exiled from Almost Everywhere (2008), set in an afterlife accessible via social media, all make clear. His journalistic nonfiction often served as critique and expose, from his early work, Campos de Níjar, about impoverished Andalusia, to 2001's Paisajes de guerra: Sarajevo, Argelia, Palestina, Chechenia.

He was also a literary critic and editor, and undertook a decades-long effort to reconnect Spain to its Muslim roots--and to remind readers of the richness of the North African, Arab and Islamic traditions in their overlapping and longstanding yet changing forms, work that strikes me as particularly salient these days.Goytisolo's frank and disarming memoirs, Coto vedado (1985), and In the Realms of Strife (En los reinos de taifa, 1986), which one of my dearest friends gave me, reminded their readers of his profound humanity and humility, and, yet again, of his fearlessness at sharing truths, his and those of the worlds in which he lived and moved. Perhaps unsurprisingly, his books, however, were banned in Spain until after Franco's death. As I noted in 2006, I was fortunate to catch him during one of periods in the late 1990s when he was lecturing at NYU, though I was too shy to introduce myself, and barely understood his Castilian Spanish. In that blog post, I mentioned Fernanda Eberstadt's New York Times Magazine profile of Goytisolo, "The Anti-Orientalist," which remains an excellent glimpse into his life.

I'll end by restating something that I'd written about back in 2011, which is that one of my favorite works of Goytisolo's is his late, slender novel The Garden of Secrets (Las semanas del jardín, 1997), which is a brilliant novel about storytelling that enacts what it explores. It contains a series of stories in multiple styles, linked through a concentrically circular form, told by various narrators who beguile as they reveal. What I found especially compelling about this novel, though, is how Goytisolo strives to remain true to the pre-literary heritage from which Goytisolo and all written literature draw, even going so far as to remove his name--Juan Goytisolo--from the novel's cover, ceding the credit to the tradition of storytelling. If there is anything antithetical to the culture of contemporary publishing, this certainly fits the bill. It may not be his greatest work, but it is representative of the artist, critic and activist that Goytisolo became, and offers pointers for anyone thinking about how to create and live in this complex, difficult, and riven world we find ourselves in today. For this book and all his others, I express my gratitude.

I never had the pleasure of meeting Bernard Hoepffner in person, but over the span of a year, and as recently as April of this year, we had exchanged emails, first about the collection of stories, and, more recently, about a volume of his long correspondence with the late American writer Guy Davenport, another original in the world of literature, that he hoped to place with a US publisher. As a translator, he was as much as an editor as any I have ever worked with, and his subtle readings of my English were often so perceptive that they enlightened me to what I had intuitively achieved--or only thought I had. Sometimes he would ask questions that forced me to justify choices, such as whether there were "falls" on a river--I was able to find links saying that there were--and whether an anachronism like "scenario" (which entered English only in 1878, as he reminded me), was appropriate for a story whose bulk was set in the 17th century. It was, I was able to say, because the story itself opens in the present, shifts back in time, and the narrative voice is constitutively unstable. In other cases, he caught errors produced by my pen listening more to my ear than eye, which then allowed me to rectify them in English and, upon his translation, French (and now, any other language).

When I communicated with him, Bernard was generous and rigorous, often witty, and capacious in his knowledge and sense of how English prose might become and work as French. As a writer and a translator, I learned a considerable deal from our exchanges, and I am applying our lessons as I write and translate new work this summer. I only wish I had been able to go to France late last summer when the book launched, which also would have provided an opportunity to meet not just my French publishers, Éditions Cambourakis, but Bernard as well. His influence among his peers in terms of opening up the body of English-language for French publishers and readers was and is significant. On his personal site, you can see how rich his trove of translations, as well as other literary and artistic projects, actually is. Here is one encomium for him from the notice in Libération: Joëlle Losfeld writes

«Il m’apportait des textes (Coleman Dowell par exemple, Guy Davenport, Joe Ashby Porter) et je lui en ai donné à traduire. Ma grande satisfaction (ce fut un sujet d’amusement entre nous) a été de lui faire connaître William Goyen qu’il ne connaissait pas, à ma grande surprise car c’est typiquement le genre d’auteur qu’il aimait lire et traduire. Bien sûr, il était pointilleux sur le choix des textes et n’acceptait pas tout, au regard de ses choix mais aussi d’un emploi du temps très chargé par l’ampleur de certaines traductions comme Ulysse par exemple. Et quand il ne pouvait pas traduire, il m’indiquait d’autres traducteurs. C’est ainsi qu’il m’a fait connaître Catherine Richard. Merveilleuse traductrice dont la démarche me semble proche de la sienne. Textes difficiles à traduire mais convertis en jeux dans leur pratique.»

(He brought me texts (Coleman Dowell for example, Guy Davenport, Joe Ashby Porter) and I gave them to him to translate. My great satisfaction (this was a subject of amusement between us) was his getting to know of William Goyen, who he wasn't familiar with, to my great surprise because it is the typical genre of author that he liked to read and translate. Of course, he was picky about the choice of texts and didn't accept everything with regard to his choices, but also because of a work schedule very filled by the size of certain translations like Ulysses, for example. And when he could not translate something, he pointed out other translators. That's how he got me to become familiar with Catherine Richard. Marvelous translator whose approach seems to me to be close to his. Difficult texts to translate but converted into games in their practice.)

Aux anges littéraires, and you can find more tributes to his life and work on the page his brother has established for him. I also hope someone will publish those Davenport letters; reading Davenport alone provides a rich education, so I can only imagine how enlightening Davenport and Hoepffner in conversation will be.

***

When I was in my 20s and first encountered the work of Juan Goytisolo (1931-2017), in particular his 1966 novel Marks of Identity (Señas de identidad), it hit me like a meteor. Not only did the story reset my thinking about how you might draw upon autobiography while writing a story that cast far wider imaginative, philosophical, political, and critical nets, but his relentless experimental method of telling it mesmerized me. What I soon learned was that this novel wasn't the then-35 year old Goytisolo's first, but his tenth, and that while he had written his late 1950s and early 1960s novels, which grappled with conditions in Francisco Franco's fascist Spain in a more conventional, social realist style, by the time he published Marks of Identity, he had begun to criticize his native country openly and harshly, and had been living in exile for a decade, in France. He never ceased his critique nor separation from his homeland, despite periodic visits much later; both extended to the end of his life.

Marks of Identity, I was also soon to grasp, was but the first in a trilogy centering on his literary stand-in, Álvaro Mendiola, and the predecessor to what is his most extraordinary and daring novel, Count Julian (La reivindicación del Conde don Julián). Published in 1970, Count Julian remains a landmark in Spanish language, European and global literature, and is one of the most brutal attacks on national tradition written from within that tradition to perhaps ever achieve major fame. In it, Goytisolo lacerates Spain's history by reinvoking and vindicating a figure thought to be one of Spain's greatest traitors, the eponymous Count Julian of Ceuta, who is said to have opened the door to the Moorish conquest. Taking the linguistic experimentation of Marks of Identity even further, but with his irony sharpened like a straight razor, his Count Julian's recitation of Spain's historical crimes woven like the dazzling threads of an exquisite tapestry as he peers through his window at the monstrous home country across the Straits of Gibraltar, Goytisolo holds nothing back. It is a breathtaking work, and won him readers across the literary landscape, though no few fans among Franco's hierarchy or the country's traditional literary world. It is telling that this magisterial, endlessly inventive writer did not win Spain's major literary prize, the Premio Miguel de Cervantes, until three years before his death, in 2014--and never won the Nobel Prize, though his vision, formal, political, spiritual, far outstrips most of the last decade of recipients of that award.

Anti-racist, anti-capitalist, anti-establishment--and ever-willing to speak out: you could characterize the bulk of Goytisolo's work this way. A Barcelona native, from a prominent family, he lost his mother to a fascist bomb as a child. His two brothers, the older Jose Augustín Goytisolo (1928-1999) and the younger Luis Goytisolo (1935-), also wrote, but Juan was the towering figure among them. After arriving in Paris Goytisolo initially worked for Gallimard, and met his future wife, novelist, publisher and screenwriter Monique Lange, soon thereafter, but, as he revealed to her and to his readers in his work, he was gay, and together they built a life that acknowledged this crucial aspect of his existence, which shifted more fully into a new form of living after her death and his move to Morocco, where he lived with two former male partners and their extended families.

As a fiction writer, Goytisolo never looked backwards in terms of his aims to push the limits of the genre or the Spanish language, as books like Juan the Landless (Juan sin tierra, 1975), the third novel in the Mendiola trilogy; Makbara (1980), set in a Muslim graveyard; Landscapes After the Battle (Paisajes después la batalla, 1985), which prefigures Houellebecq's Submission, but in more inventive and anti-Islamophobic way; Quarantine (Cuarantena, 1991), which explores the AIDS pandemic; Marx Family Saga (1999, La saga de los Marx, 1993), a witty novel about the Communist founder and his family; and his final novel, Exiled from Almost Everywhere (2008), set in an afterlife accessible via social media, all make clear. His journalistic nonfiction often served as critique and expose, from his early work, Campos de Níjar, about impoverished Andalusia, to 2001's Paisajes de guerra: Sarajevo, Argelia, Palestina, Chechenia.

He was also a literary critic and editor, and undertook a decades-long effort to reconnect Spain to its Muslim roots--and to remind readers of the richness of the North African, Arab and Islamic traditions in their overlapping and longstanding yet changing forms, work that strikes me as particularly salient these days.Goytisolo's frank and disarming memoirs, Coto vedado (1985), and In the Realms of Strife (En los reinos de taifa, 1986), which one of my dearest friends gave me, reminded their readers of his profound humanity and humility, and, yet again, of his fearlessness at sharing truths, his and those of the worlds in which he lived and moved. Perhaps unsurprisingly, his books, however, were banned in Spain until after Franco's death. As I noted in 2006, I was fortunate to catch him during one of periods in the late 1990s when he was lecturing at NYU, though I was too shy to introduce myself, and barely understood his Castilian Spanish. In that blog post, I mentioned Fernanda Eberstadt's New York Times Magazine profile of Goytisolo, "The Anti-Orientalist," which remains an excellent glimpse into his life.

I'll end by restating something that I'd written about back in 2011, which is that one of my favorite works of Goytisolo's is his late, slender novel The Garden of Secrets (Las semanas del jardín, 1997), which is a brilliant novel about storytelling that enacts what it explores. It contains a series of stories in multiple styles, linked through a concentrically circular form, told by various narrators who beguile as they reveal. What I found especially compelling about this novel, though, is how Goytisolo strives to remain true to the pre-literary heritage from which Goytisolo and all written literature draw, even going so far as to remove his name--Juan Goytisolo--from the novel's cover, ceding the credit to the tradition of storytelling. If there is anything antithetical to the culture of contemporary publishing, this certainly fits the bill. It may not be his greatest work, but it is representative of the artist, critic and activist that Goytisolo became, and offers pointers for anyone thinking about how to create and live in this complex, difficult, and riven world we find ourselves in today. For this book and all his others, I express my gratitude.

The first involved reading and taking notes on the book,

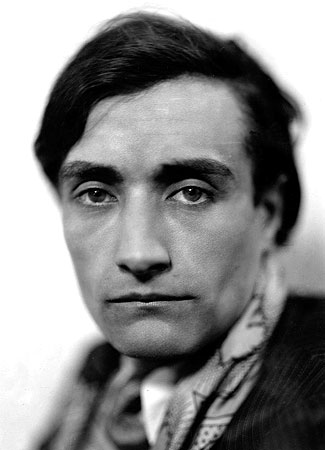

The first involved reading and taking notes on the book,  I saw several routes into this connection between Taïa's novel and Artaud's (at right, Guardian UK,

I saw several routes into this connection between Taïa's novel and Artaud's (at right, Guardian UK,  While I didn't manage to get to the pricey

While I didn't manage to get to the pricey

Often I'll come across something in one of the papers I regularly scan and note it for a future blog post on here, only to not get around to it because of one thing or another, but I can always count on Reggie to buzz me with an email that gets me thinking. He recently sent links to two articles I'd seen, on

Often I'll come across something in one of the papers I regularly scan and note it for a future blog post on here, only to not get around to it because of one thing or another, but I can always count on Reggie to buzz me with an email that gets me thinking. He recently sent links to two articles I'd seen, on

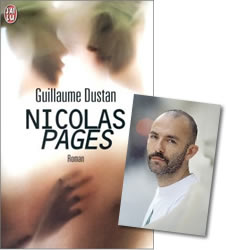

The editor of the series was a writer I in my ignorance had never heard of, though he was already zooming down the path of becoming one of the most notorious and exciting figures in contemporary French publishing:

The editor of the series was a writer I in my ignorance had never heard of, though he was already zooming down the path of becoming one of the most notorious and exciting figures in contemporary French publishing: