|

| Marianne Moore and Muhammad Ali,in 1967 |

In fact, I sometimes think that the deceptive simplicity and apparent naturalism of Moore's work leads readers, as it did for me, to assume they will "get" her work when in fact its complexity is right there before your eyes. But a little deeper reading usually opens the poem's meanings up, like paper flowers unfolding in water. Like Elizabeth Bishop (1917-1979), Moore's poems also avoid, at least on the surface, the personal and confessional, but her variable perspective on the world does eventually become clear, and that surface control seems at times to lie atop something burbling below, a rich vein of feeling. (As Dan Chiasson discussed in his thoughtful review, Linda Leavell's acclaimed 2013 biography of Moore, Holding on Upside Down (FSG), reveals how much personal tumult the seemingly placid Moore did live through, from childhood on.)

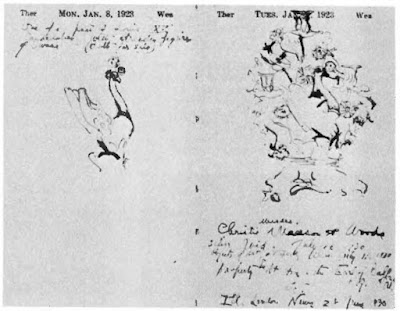

"No Swan So Fine" is one of Moore's briefest masterpieces, unsurpassed in its music, precision, wit, and irony. I taught it most recently in "Foundations of Literary Studies," Rutgers-Newark's introductory course for potential undergraduate English majors and minors, and it left most of the students bemused, until we walked through it together and, as is so often with Moore's poems, it clicked. They started to get it and wanted to talk about it; some did with considerable exuberance. It was the direct result, critics have pointed out, of Moore's lifelong observation and careful notation. Scholar Patricia Willis writes that in March 1930, Moore saw in the Illustrated London News a pair of Louis XV candelabra, the "property of the late Lord Balfour," a friend of her friend, British critic George Saintsbury (1845-1933), to whom she had sent a condolence about Balfour earlier that year. She even sketched them (see below).

A year later Moore read a New York Times Magazine article (19 May 1913, pp. 8-9), by Percy Philip, about the Rockefellers' restoration of Versailles, and notated above a clipping of one of the featured images (cf. below) the line "There is no water so still as the dead fountains of Versailles." I find it fascinating to consider how she fits that resonant aperçu into the poem, leaving it as a prose quotation but transforming it into poetry, not unlike the poem itself, which unfolds as an argument attempting to make sense of disparate and contrasting images, artifacts, ideas. The overtly rococo language not only evokes Louis XV but embodies that era--"with swart blind look askance / and ambidextrous legs, so fine / as the chintz china one with fawn - / brown eyes and toothed gold..." This tongue-twisting ornateness, which is nevertheless not superficial but full of depth and seriousness, continues in the second stanza, culminating in that falling final sentence, like a guillotine.

Lastly, the theme of the past and the evanescence of culture was in Moore's mind as well because, as Willis adds, she wrote the poem to commemorate the 20th anniversary of Poetry magazine, but with the thought that it would shutter that spring; it is, however, thankfully still with us, and Moore's poem appeared in that October 1932 issue, alongside poems by Carl Sandburg, Wallace Stevens, Witter Bynner, Eunice Tietjens, and others. Here, then is the poem:

|

| Moore's poem, copyright © Poetry Magazine |

And now, those images--the candelabra, Moore's sketch, and the clipping (all from the Marianne Moore Archive Online):

|

| The actual swan candelabra sold at Christie's |

and

|

| Moore's sketches of the candelabra |

and

|

| From the New York Times Magazine: "The Tapis Vert at Versailles Where Melancholy Now Reigns as Queen" |

No comments:

Post a Comment