1. More than anything about the World Trade Center before 2001, I remember the subterranean maze of the concourse, always pulsing with the hustle and bustle of people zooming from one set of trains to the next, gliding from restaurants to stores, moving, always moving beneath the vast, windy, unwelcoming plaza. I remember sitting upstairs outside and hearing a jazz band perform there, its melodies wafting off in the relentless summer air. I remember holding down food wrappers so that they wouldn't blow away as I tried to each lunch; I remember always perceiving the impossibly tall towers looming above as so high and immense that it dizzied me to look up as I stood beneath them. I remember going up to the top, to the observation area, and feeling something akin to vertigo, despite the sublime portrait of the city spreading out before me. I did it once and vowed I would never do it again. For years I could not grasp the geography of the plaza, the train stations, the streets, anything of that portion of lower Manhattan

above ground, but the concourse I grasped almost immediately. Even today when I ascend the steep escalators from the lower level where the PATH trains power in from New Jersey, in almost Pavlovian fashion I look for that concourse. My memory walks it even if I follow the new route, fully understood and memorized, towards the terminal at Fulton Street.

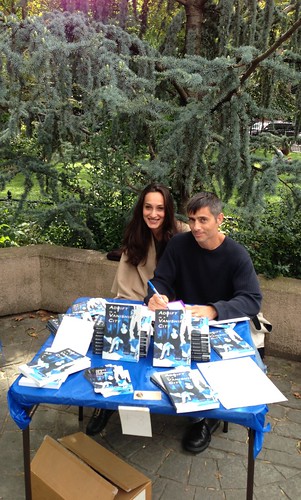

2. In 2000, I read in the Barnes & Noble beneath the World Trade Center towers, with Asha Bandele. I cannot remember who invited us, or why we were paired together, but I recall enjoying meeting her, and I recall the reading, at which she read from her memoir

The Prisoner's Wife, and I read poems. New York 1 taped and broadcast us, and the screening of that reading provided me with the only bit of public fame I have ever had (outside of a childhood performance as John Henry at Loreto-Hilton during the Bicentennial Year, and among adolescent readers of my poetry in Sicily). Several times people recognized me on the street, including in the post office on 10th Street, off 6th Avenue. My poems were nothing to speak of, but one wasn't so bad, a paean to Jackie Robinson and St. Louis, and an old man even blurted out to me, apropos of nothing but his delight at seeing someone from TV, "I liked your baseball poem." That experience seared into my consciousness the power of television, but also made me wonder later what show had broadcast our event, why couldn't I find the email or notes of who had invited me to participate, why everything but the aftermath of the reading was such a blur. I cannot even say that I remember

where in that concourse the Barnes & Noble was, though I do know I went in there once or twice just to browse. Does that tape of that reading even still exist, and would it not be too macabre to see it now?

3. On the morning of September 11, 2001...well, I have recounted this many times elsewhere, but I will only say that I had begun the second stage of my commuting-to-teach life, to Providence, for a wonderful year-long stint for which I will always be grateful. That day was the first I was supposed to teach. It goes without saying that it was tumultuous, wrenching, impossible. I did not know if my partner and his colleague were on one of the hijacked, weaponized planes. I did not know if there were other attacks, as the landlady of the little inn where I was lodging asserted, based on what she had seen on TV. We watched it that morning together, in shock and horror. I did not know if I could even bear to teach, or if my students could sit through a class. (I did, they could, we all were nevertheless shaken.) What I most recollect about that day, beyond seeing the towers being attacked on TV, beyond the cars with open doors broadcasting the news, beyond several of my colleagues breaking down in tears, beyond trying, using the rotary phone in the old building where the Creative Writing (Literary Arts) Program was then housed, to reach C and make sure that he was okay, was the seemingly interminable faculty meeting I and everyone else had to sit through, some of the senior people on the verge of breaking down. We went through every bullet point on the agenda. Every single one. I don't, however, remember getting my university ID card, which still bears the proof that it was issued that afternoon: September 11, 2001.

4. The hysteria and spectacle that rightly or wrongly followed the terrible events of 9/11 caught and continue to snare us in their net. On the train I rode back to New York the following day, September 12, a phalanx of police--local, state, auxiliary, etc.--scoured every car, with dogs and machine guns in tow, based on the report of man in a turban carrying a knife. The terrorists had seen fit to continue, by way of Providence. It turned out to be a Sikh passenger carrying his ritual knife, though I did not learn this until the train finally was pulling into New York City, which was on high alert given the tragedy that had just unfolded and was still ongoing. I and everyone else got off that train even more frazzled that we could have imagined. There were more reports and accounts of attacks or strange incidents on the day of the attacks and in the days after, but all were but immediately efflorescences, soon to lose their horrible blooms, of a trauma that lingered, that still lingers, a decade on.

5. In the days and weeks, in the months after 9/11, New York City felt ghostly--figuratively, and literally. There was the gravesite, a smoldering wound, at which thousands of people had died, and legions were working heroically to search. There were the many people who had lost loved ones, the many who had escaped, the many, like a friend of ours who was living in Battery Park City at the time, who lost everything but their lives, and were displaced. There was a vulnerability and fear so raw they might erupt like a volcano, and a resolve and determination as strong as the most tempered armor. But what was going to become of New York? And to a lesser degree, New Jersey, which is always hasped to the city but so easily and readily forgotten? Friends of ours moved away; they couldn't deal with the undiminished horror, the danger, the uncertainty. Some went "home"; some moved to Atlanta; some just scattered to wherever life took them. One of my closest friends, a brilliant man, began to suffer a nervous breakdown shortly after the attacks from which he never recovered. He is, the last I heard, still homeless. Every September the city holds its memorial for those lost in the attacks, and there is a memorial museum which will anchor memories for the rest of time; the site where they occurred is transforming into a New York-style zone of nostalgia and commerce; and the empty storefronts and makeshift tributes and scars of 12 years ago are mostly erased, having given way to luxury skyscrapers and bike lanes and bedizened parks and a level of prosperity, at least among the super-rich, to rival the Gilded Age. The wound remains, if concealed. All who lived through that moment carry it around, and those who have arrived since do to, even if they cannot feel or imagine it.

6. That wound: the city, the country, and the globe have never fully recovered. The horrific attacks became the pretext for wrongheaded, unending wars, a monstrous hyper-surveillance and security state, a military-industrial complex so out of control, so rapacious, that we are yet again at the precipice of an unnecessary, ill-conceived, potentially disastrous intervention that an overwhelming majority of Americans, and people across the globe, do not want to occur. We have a nebulous "War on Terror" that is as unjustifiable today as it was shortly after 9/11. Meanwhile, so many basic questions surrounding the 9/11 attacks have never been answered satisfactorily. We have rampant spying on American citizens and, as we have learned from Edward Snowden's disclosures, on everyone and everything across the globe that moves or breathes, have had it

since before 9/11, but we still have no assurance that the basic sharing of classified, flagged information, that would have prevented or at least stunted the attacks in 2001, is occurring. Despite the fact that Russia tried to warn the US about one of the terror suspects in the Boston Marathon bombing, he was still able to proceed to his murderous goals. Yet we are told lie after lie about the entire security apparatus we are living under, at the same time we hear the word freedom uttered as readily as greetings. Are we free? Were we ever? We certainly are, by many measures,

far less free. That is one of the wounds we all live with. All the airport security theater, the secret courts and unwarranted warrantless wiretapping, the cameras on every corner and in every hallway, the truly nefarious militarization of law enforcement, and of our culture: these are all signs of that still open wound. They are symptoms of a fever that has not broken. They are the residue of our inability to deal with the root causes of what led to those terrible attacks. Someday, perhaps in my lifetime, we will come together and figure out why we did not do what we needed to before the fact, why we persist in the grip of our delusion, why we cannot rightly diagnose the problem, ourselves, and prescribe the right medicine. We do not have to live this way. But we will continue to unless we recognize why we do.

7. I wrote, on the train heading and returning, on the comforter-covered bed in the inn where I stayed, at my desk at our old apartment from which we once could see the Empire State Building, the Chrysler Building, and the Twin Towers, a short piece, a fragment, that was to be the beginning of a longer work. I was never able to finish it. I published it in an anthology edited by the friend of a friend, a professor at NYU. I had not thought it dealt at all with 9/11, but it was if I had distilled the moment before and the long period after into a dialogue, or monologue, depending, that could not go any further. The echo of that failure, of the absent text that was supposed to precede what I had written, haunted me for years. I used to think, if only I could have forced it, but those voices were meant to go where they were meant to go.

7. I am mildly obsessed with photographing--to the point of having to stop myself at times--the new World Trade Center Tower, the Freedom Tower, which may not be its name any longer and which sounds jingoistic and hyperbolic, though I have that name stuck in my head and when I see the tower, which is visible from Jersey City, from Hoboken, from Bayonne, from many a vista in Manhattan, which looms above everything, that name comes to mind. It has not erased the Twin Towers in my mind, but it has joined them. I see the one tower but somewhere, in a chamber of my thinking, there are three. Tonight the original two are columns of bluish-white light, but when I pass by the solid, impregnable base of the new tower, the Freedom Tower, a giant obelisk of steel and glass and who knows what else, those invisible towers, that unmanageable plaza, the phantasm of that teaming concourse return. The head can hold as much or more than it can bear. Memory can hold even more. We cannot and must not forget what happened on September 11, 2001, or all who died that day and afterwards as a result of the attacks, or all those who essentially gave their lives and health in the process of rescue and recovery, or all those who lost loved ones and continue on with those losses inside. We cannot and must not forget as well what has transpired since those attacks, what we as a nation have become, what sense of the world we had as a people, and what it will take to recover it.