|

| The Charles Ives House in Redding, Connecticut |

Danbury, Connecticut native

Charles Ives (1874-1954) was one of the most original composers the US has produced, a genius to the ears of

Arnold Schoenberg, another genius and his exact contemporary, and to those of many others, including

Gustav Mahler, Leonard Bernstein, Leopold Stokowski, and

José Serebrier. Like his soundworld, with its competing and often clashing layers of melody and harmony, rhythms and tonalities, Ives's composing career was idiosyncratic; he spent most of his daily working life as an insurance company executive in

New York, and allegedly did not compose anything for the last 17 years of his life. Up till that point, however, he produce a slew of works that challenged the conventions of his era, and even today many of them strike the listener with their strange, otherworldly qualities. Ives's final home outside New York was in

Redding, Connecticut, and as of last year,

Charles Ives Tyler, Ives's grandson, had placed it on the market, and so it was in danger of being leveled, given the value of the land beneath it, its ramshackle state, and the presence of and desire for much larger homes nearby.

In early August

Norman Lebrecht's Slipped Disc music blog posted about cellist and performance artist

Zoe Martlew's attempts to alert the public's attention to the house's fate; her efforts and others' quickly stirred supporters, including the

Charles Ives Society, based at the

University of Illinois, into finding some means of preserving the residence,

which still holds some valuable relics of Ives' life there, as Martlew saw when she visited the house with composer and conductor

Oliver Knussen. It was here that Ives composed some of his finest and most original music, including the "Concord Sonata" and his radical, almost unperformable Fourth Symphony, which wasn't premiered until over a decade after his death.

|

| Pictures (c) Zoe Martlew/Lebrecht Music & Arts |

|

| Pictures (c) Zoe Martlew/Lebrecht Music & Arts |

Among the proposed actions to rescue the house was

a petition to President Barack Obama (but why not, I wondered, Connecticut governor

Dannel Malloy, or, as someone on Lebrecht's blog suggested, the

US Representative for that area,

James Himes (D-CT) ?).

Robert Eschbach, a music professor at the

University of New Hampshire, established a Save the Ives House

Facebook page. More practicable, it turns out, was finding some Ives fan or fans, or a coalition of them, to buy Ives's house. Now, according to

WQXR Radio,

it appears that that is happening, with the Charles Ives Society taking the lead in trying to raise the $1.5 million to purchase the house, an 18+-acre estate that also includes a cottage and barn, from Tyler, and

Nikola Ragusa also

setting up a fundraising page on Indiegogo to raise money as well.

|

| Kevin Hagen for The Wall Street Journal |

|

| Kevin Hagen for The Wall Street Journal |

This is only the first step, though; even if taken off the market and

transformed into an artists' retreat, there are further unresolved issues, as WQXR points out, including zoning and related real estate issues; tax status; further funding for renovations and making the house accessible to visitors; the endowment of the "housing complex," as it were; the estate's location on a residential street, and so on. The institution running Ives' birthplace museum in Danbury faced such severe financial problems it had to furlough its tiny staff. The ongoing economic crisis has poses perils for arts institutions of all kinds, and the Ives House in Redding, even if saved from purchase-to-demolition, will still not be out of the woodpile without much, much more support.

***

|

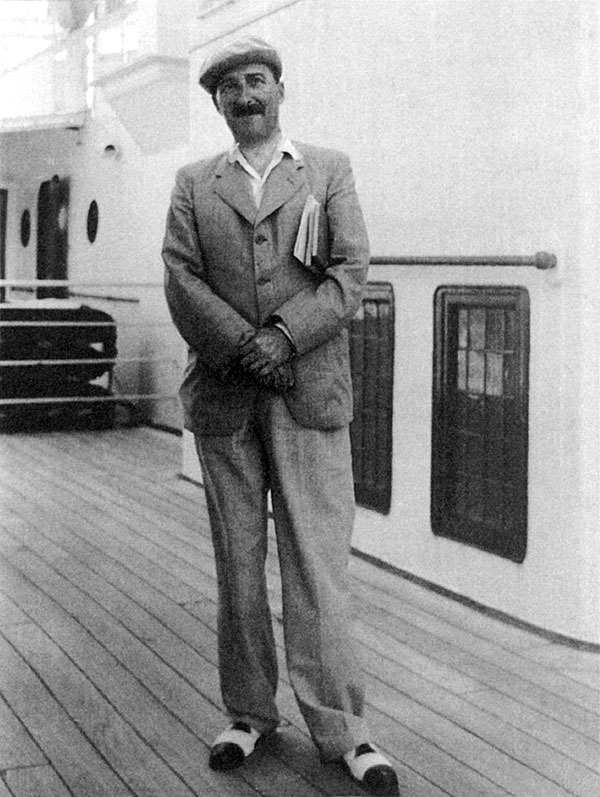

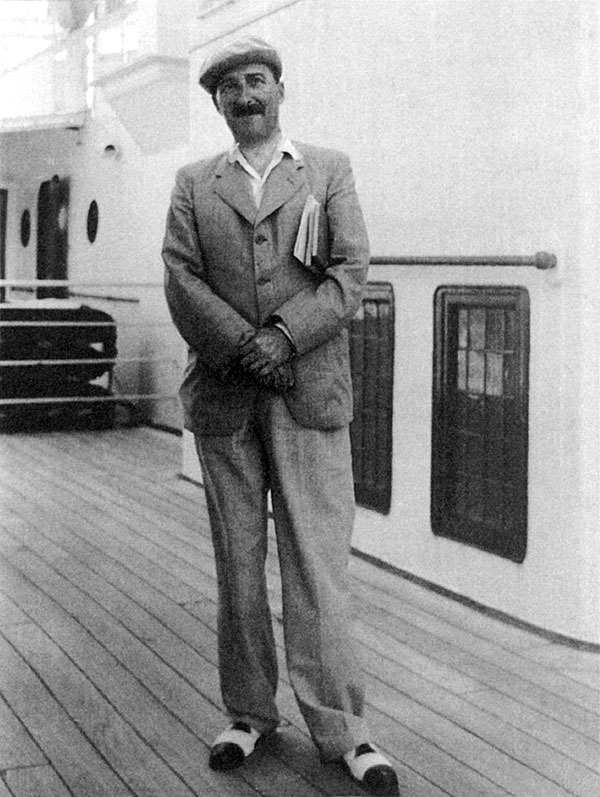

| @ CSZ Arquivo |

|

| Stefan Zweig (@ CSZ Arquivo) |

Halfway around the world, on the other side of the Equator, a famous artist's residence, brief though it was, has been preserved. North of Rio de Janeiro, in Petrópolis, the former summer resort city of Brazil's imperial family, the final home of the prodigious Austrian writer and librettist Stefan Zweig (1882-1942) and his second wife Lotte Altmann. It was in this home that Zweig and his wife, in flight from the Nazi regime dominating large swaths of Europe and thus cut off from the world they had known, and despairing for the future, lived for five months, with Zweig finishing his memoir The World of Yesterday; one of his finest works of fiction, The Chess Novella; and his perceptive survey of the country to which he had only just moved, Brazil, Country of the Future, before committing joint suicide. Thus did he terminate what had been one of the major literary careers of the era.

The

Casa Stefan Zweig (CSZ - Stefan Zweig House) received its earliest support shortly after Zweig died, when Brazilian author

Raúl Azevedo proposed that the house be turned into a museum to honor the stateless refugee. His own heirs subsequently offered Brazil the contents of his dwelling in London, where he had lived before departing first for New York, and then to Brazil. It was not until over half a century later, however, that fans of Zweig were able to purchase the house and transform it into a museum. The house opened

as a Zweig museum and archive, and as a cultural center, on July 29, and is open Fridays through Sundays, 11 am - 6 pm, with free admission. Among the artifacts available for view are 560 volumes, works in the original German, other manuscripts including annotated ones for future works, personal objects, autographed photos from close friends such as

Richard Strauss and

Sigmund Freud, and some of his extraordinary collection of original musical scores.

|

| The Casa Stefan Zweig © Manfred Grietens |

|

| © arquivo |

Rather bizarrrely,

English Heritage turned down the application to honor Zweig with a plaque on the London house where he lived

for five years. In addition to claiming that Zweig's status in Britain was not as high as elsewhere, it also stated that "it was felt that a critical consensus does not appear to exist at the moment regarding Zweig's reputation as a writer and that, as a consequence, it was not possible to be certain of his lasting contribution." During his lifetime up through his flight from the Nazis, his fiction, poetry, plays, histories, belles-lettres, and journalism received both acclaim and a large readership, in Europe, the United States, and South America, to the extent of being turned into major Hollywood films in several cases, and after the death of Strauss's longtime collaborator

Hugo von Hoffmannsthal, Zweig wrote two libretti for Strauss

's operas, having to do so secretly towards the end because of the proscription against his work laid down by the Nazis. Yet to the British preservationists, Zweig does not rank. Or not highly enough. So be it. A trip to Petrópolis sounds like a far more inviting option anyways.

No comments:

Post a Comment