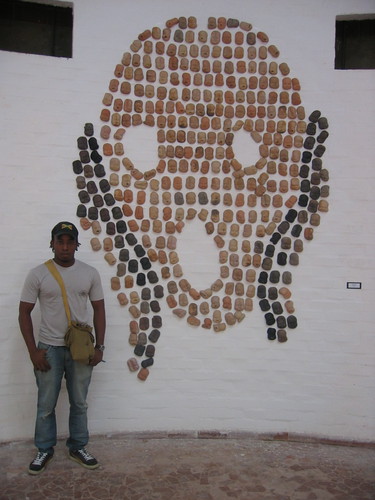

I will post about the Cuba trip later today, but I wanted to note to recent departures from the world of arts and letters, one I heard about only when I got back (I had almost no net access while away),

Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, and one I read about this morning,

J. G. Ballard. Both Sedgwick and Ballard were pathblazers, in very different ways, and global literary studies in the former's case, and fiction and science fiction in the latter's, would look quite different had they not appeared. Both have also been very important to me in many ways, as a creative writer, as a teacher, as a critic, and as someone trying always to think about how we see the world and the multifarious ways it works. Both were quite fearless in their work; for Sedgwick it meant trampling on binaristic assumptions that still grip our public and private discourses when it comes to gender and sexuality and how they function in the world, while for Ballard, it involved writing texts that could be read as pessimistic, anti-humanistic, sexist, and obscene. Not that such criticisms stopped either of them.

In the case of Kosofsky Sedgwick, as is now well known, her first two studies,

Between Men: English Literature and Male Homosocial Desire (1985), and

The Epistemology of the Closet (1990) and

Tendencies (1993), the text I have studied most closely, have been foundational in what many scholars, students, artists, critics, and increasingly the broader public may now take for granted, the field of

queer studies, and the articulation of much more complex readings of the relationship between gender, sexuality, literary and cultural texts, discourse, performance, and related concepts. With each of these studies, the complexity of her argument, and her openness to a range of possible conceptual and performative axes, expanded. These critical texts, along with her teaching, raft of other publications, and public conversations and advocacy with an wide array of other notable scholars, artists and critics in and around gender, queer and performance studies, liberatory politics and practice/praxis, and critical theory, have remade the critical landscape in many humanities fields, while also helping to change discussions about the role of critics in shaping the public discourse around these topics. Though a self-described straight woman, she was truly emblematic of the complex and beautiful queerness she explicated and explored. Eve Sedgwick befriended and championed the work of the important, late black queer writer

Gary Fisher (

Gary In Your Pocket: Stories and Notebooks of Gary Fisher [1996]). (I should note that I recall the time I first heard her speak about Fisher, just before the book came out, and took her role in its production and publication quite skeptically, though

Robert Reid-Pharr calmed me in the moment, and later I read the book and, after much rumination--because it is still a difficult book for me to take on many levels--and came to appreciate it, Fisher, and her role in bringing it into the world.) She was also a poet in her own right (

Fat Art, Thin Art [1994]), which, like the playful essays in

Tendencies, offered her another critical mode (why oh why do so few scholars not follow her example in this regard?). She had taught at a number of institutions, including

Duke University and most recently the

City University of New York's Graduate Center. She was only 58.

J. G. Ballard, a Shanghai native and trained physician, was one of the leading British and English-language experimentalists and of the late 20th century. His works could easily be described as "queer" in a different sense; they are often called science fiction or dystopic fiction, but in a number of them, at the level of narrative, they defy categorization. It's easy to forget, given the popularity of his more mainstream books, such as

Empire of the Sun (1984), which later became an acclaimed

Steven Spielberg film, which obituaries today have been highlighting, and

The Kindness of Women (1991), how utterly strange and singular books like

The Crystal World (1966),

Crash (1973), which David Cronenberg masterfully turned into a cinematic shocker in 1996,

Concrete Island (1974), and my personal favorite, one of the most perverse, draw-dropping, and horrifyingly sublime books in all of English-language literature,

The Atrocity Exhibition* (1969) really are. Riding the genre line multiple ways and breaking not only formal boundaries but thematic and content ones as well, Ballard managed to delve perhaps more deeply than many of his fiction-writing peers into the ways in which our endlessly and excessively technologically mediated society was transforming, in a phenomenological sense and at a neuropsychological level, our experiences of the world. As his readers know, an adjective, Ballardian, has been coined to describe essential aspects of his style and dystopian thematics. The proliferation and normalization of paraphilias far beyond concerns about sexuality and pornography, the incessant and life-devouring obsession with mass media and hypercelebrity, the increasing struggle and ecological destruction produced by capitalism's churning engine, the spreading paranoia produced by the creeping global, govenrmental and corporate panoptican, and so much more, can be found in germinal and distilled versions throughout his oeuvre. This body of work influenced a wide range of artists across fields, but especially other fiction writers and many musicians, including groups such as

Joy Division, The Normal, the Buggles, Jawbox, Radiohead, and many others. And Ballard did not let up: one of the last novels he wrote that I read,

Super-Cannes (2000), refines these interests into what appears to be a straightforward realist narrative that slowly but surely turns bizarre, in quintessential late Ballardian style. He also published nearly two dozen collections of stories, a collection of essays, and an autobiography, and also wrote for film and TV. He was 78.

*As I never tire of telling students, there are different forms of censorship. Apocryphally Ballard experienced one form in the US when publisher

Nelson Doubleday decided to glance at Ballard's

The Atrocity Exhibition and was so disturbed--very likely by the references to the late President Kennedy and his widow, and to the extremely graphic short story/chapter whose title included the words "Ronald Reagan" (Ballard was quite a visionary)--that he ordered the entire press run pulped. The entire press run. Jonathan Cape published the volume in the UK, and it later appeared in the US first under a different title, and then under Sylvère Lotringer's Re/Search imprint, with fetching graphic photos. You're forwarned....

>>>

The poem I'm choosing today is by one of my favorite poets,

Adrienne Rich, and it's from her "Twenty-One Love Poems," which appeared first as a stand-alone collection in 1976 and then in her volume

The Dream of a Common Language (1978). It is worth reading all 21 of these poems, as they economically and incomparably demonstrate poetry's capacity to express desire and love--and in the case of these poems, specifically the love between women. Thinking of Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick and J. G. Ballard, I am posting Poem VII, "What kind of beast would turn its life into words?"

Love Poem VIIWhat kind of beast would turn its life into words?

What atonement is this all about?

--and yet, writing words like these, I'm also living.

Is all this close to the wolverines' howled signals,

that modulated cantata of the wild?

or, when away from you I try to create you in words,

am I simply using you, like a river or a war?

And how have I used rivers, how have I used wars

to escape writing the worst thing of all--

not the crimes of others, not even our own death,

but the failure to want our freedom passionate enough

so that blighted elms, sick rivers, massacres would seem

mere emblems of that desecration of ourselves?

Copyright © 1988, from

Gay & Lesbian Poetry In Our Time, Carl Morse and Joan Larkin, editors, New York, St. Martin's Press. All rights reserved.

This past winter quarter, I taught excerpts from Bhanu Kapil's narrative Incubation: A Space for Monsters (Leon Works, 2006--also a former J's Theater Book of the Month pick), as part of my unit on transhumanism/posthumanism, a topic my colleague Alex Weheliye had first hipped me to some years ago, but which it took me, in my usual fashion, a while to assemble in my head. (Tisa B., the Afro-futurists, and others also pointed the way forward.) I'm not sure how much the students got from our conversation about the book, which I felt was a bit rushed given the time constraints--in my ideal class we would have many, many weeks to luxuriate in reading and discussing any text or film or performance we were exploring--but in rereading it, I was struck again by what a remarkable little intervention it is. At its heart are a series of complex and artful algorithms connecting the immigrant Other to the alien/cyborg, based on her own experiences but also reconstructed as a lattice of interlinking and interanimating images, metaphors and metonyms, and structured as a chain of linked narratives. It is an incubatory space, not just for monsters, but for thinking itself. Here're two passages that work as an excerpt and give a sense, in distilled form, of what she achieves in this book. Enjoy!

This past winter quarter, I taught excerpts from Bhanu Kapil's narrative Incubation: A Space for Monsters (Leon Works, 2006--also a former J's Theater Book of the Month pick), as part of my unit on transhumanism/posthumanism, a topic my colleague Alex Weheliye had first hipped me to some years ago, but which it took me, in my usual fashion, a while to assemble in my head. (Tisa B., the Afro-futurists, and others also pointed the way forward.) I'm not sure how much the students got from our conversation about the book, which I felt was a bit rushed given the time constraints--in my ideal class we would have many, many weeks to luxuriate in reading and discussing any text or film or performance we were exploring--but in rereading it, I was struck again by what a remarkable little intervention it is. At its heart are a series of complex and artful algorithms connecting the immigrant Other to the alien/cyborg, based on her own experiences but also reconstructed as a lattice of interlinking and interanimating images, metaphors and metonyms, and structured as a chain of linked narratives. It is an incubatory space, not just for monsters, but for thinking itself. Here're two passages that work as an excerpt and give a sense, in distilled form, of what she achieves in this book. Enjoy!

Infrequently I find myself browsing through a literary journal, and I come across something I hadn't seen before. And so it was with the

Infrequently I find myself browsing through a literary journal, and I come across something I hadn't seen before. And so it was with the

In the case of Kosofsky Sedgwick, as is now well known, her first two studies,

In the case of Kosofsky Sedgwick, as is now well known, her first two studies,  J. G. Ballard, a Shanghai native and trained physician, was one of the leading British and English-language experimentalists and of the late 20th century. His works could easily be described as "queer" in a different sense; they are often called science fiction or dystopic fiction, but in a number of them, at the level of narrative, they defy categorization. It's easy to forget, given the popularity of his more mainstream books, such as Empire of the Sun (1984), which later became an acclaimed

J. G. Ballard, a Shanghai native and trained physician, was one of the leading British and English-language experimentalists and of the late 20th century. His works could easily be described as "queer" in a different sense; they are often called science fiction or dystopic fiction, but in a number of them, at the level of narrative, they defy categorization. It's easy to forget, given the popularity of his more mainstream books, such as Empire of the Sun (1984), which later became an acclaimed  The poem I'm choosing today is by one of my favorite poets,

The poem I'm choosing today is by one of my favorite poets,

(finally posted)

(finally posted) A few years ago, I came across

A few years ago, I came across

(finally posted)

(finally posted)

(finally posted)

(finally posted)

I'm on my way to Cuba, as part of an educators' tour sponsored by the

I'm on my way to Cuba, as part of an educators' tour sponsored by the  And another great contemporary poet and one of my former Cave Canem teachers: Harryette Mullen. (Sooner or later I'll have poems by all of them up here.) As the poem below shows, she has enough wit to fuel the mothership. It's from the

And another great contemporary poet and one of my former Cave Canem teachers: Harryette Mullen. (Sooner or later I'll have poems by all of them up here.) As the poem below shows, she has enough wit to fuel the mothership. It's from the  The following poem is by one of my favorite poets,

The following poem is by one of my favorite poets,

I'm traveling for the next week or so (I'll say more soon), and thus I'll be posting poems perhaps more sporadically than less, and if so, probably without commentary (depending upon my Internet access), so let me try to get a few up before I'm off for a while. Here's a poem by Wole Soyinka, the great Nigerian author and Nobel laureate, known best for his plays and fiction, but who is also a remarkable poet. The following poem really needs no introduction at all.

I'm traveling for the next week or so (I'll say more soon), and thus I'll be posting poems perhaps more sporadically than less, and if so, probably without commentary (depending upon my Internet access), so let me try to get a few up before I'm off for a while. Here's a poem by Wole Soyinka, the great Nigerian author and Nobel laureate, known best for his plays and fiction, but who is also a remarkable poet. The following poem really needs no introduction at all. Today's poetry selection is by

Today's poetry selection is by  It's officially Opening Day for the 2009 baseball season (the first game was played yesterday), and my ardor has cooled. Perhaps it's age or my mind on a different trip for a change or mental exhaustion, who knows, but I figure it'll gin up again after a weeks. Across the media spectrum the

It's officially Opening Day for the 2009 baseball season (the first game was played yesterday), and my ardor has cooled. Perhaps it's age or my mind on a different trip for a change or mental exhaustion, who knows, but I figure it'll gin up again after a weeks. Across the media spectrum the  At the

At the  Today's poet was only an incidental reference to me at first, an attribution ("after

Today's poet was only an incidental reference to me at first, an attribution ("after