|

| The line around the atrium |

This Sunday, the blockbuster New York art show of the year,

Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, will finally close. Having opened on May 4, it was set to end this past Sunday, but the Met wisely decided to extend it a week to allow stragglers--thousands of them, including yours truly--to catch it. Several friends had urged me to check it out as soon as I got back from

Chicago in June, but I kept thinking I would go eventually and then, as always happens during the summer...the clock wound down. So I headed uptown on Wednesday, thinking that midweek in the early afternoon would be fairly slow, only to find that the wait (for non-Met members, I later learned) was estimated at

2 1/2 HOURS at best, and that the line I joined, which doubled back at its start, stretched all the way around the main atrium of the Met up through the 19th Century European Art galleries. It was probably about 3/4ths of a mile, if not the entire length. And the Met's atrium was warm. Quite warm. And endless line in a hot space is not a good combination.

|

| My notebook drawings of Savage Beauty |

|

| The line |

So long was the wait that I twice considered quitting the line and just heading straight to grab something to eat and then going to the library, but by the time I'd made it halfway around the atrium, I decided to stick it out. I had also worn my daily library-ready backpack, which meant I had my (heavy and growing ever heavier by the minute) laptop (whose screen had to be inspected by museum guards), books and notebooks, and writing materials stuffed in it. Perhaps an hour into the wait, the weight felt like one of

Auguste Rodin's statues--the big ones--was nesting on my shoulders, and even though I kept setting it down as the line moved, by the time I got to the exhibit I felt like I'd carried one of

Richard Serra's large tilting steel arcs the entire length of the line. (There was a show of Serra's drawings that intrigued me, but I was too exhausted to stick it out after the McQueen mosh.)

|

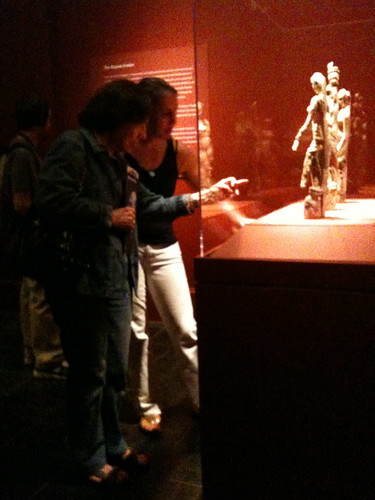

| Entering the exhibit |

Before I say anything about the exhibit, let me also add that as much as I love Alexander McQueen's work and a great deal of the Met's innumerable treasures, it is

very, very unpleasant to be packed into a museum exhibit as if one were on an extremely crowded subway train; the 6 heading north or south at rush hour comes to mind. Show-as-spectacle is a moneymaker for the museums, but for the viewers, it becomes as much about the experience of the spectacle as about the artworks themselves. In addition to not being able to see anything, every step, every turn, every movement is impeded by all of the others around you trying to do the same thing, move, look, experience. To see artwork of any sort in depth, to take it in as fully as possible, you--I--need a bit of space and time. But that was not to be. It was a moshpit in the galleries, and when I realized that I'd accidentally walked past one of alcoves and tried to go back, it was like scaling the wall beneath a cataract, with the momentum completely against me and only my determination (and madness) keeping me pressing ahead. I did manage to slip back into that other gallery, and was glad I did. But what a workout! Yet such is the nature of blockbusters and the experience of catching such spectacles at their end, especially in New York City in the summer. And perhaps a bit of discomfort was necessary to fully engage with and experience this show.

|

| My notebook drawings of Savage Beauty |

In fact, I was very glad I stuck out that line and the quicksand of fellow exhibitgoers to catch the show, because while I have long been a fan of McQueen's work, having even watched his last full, incalculably brilliant runway show during his lifetime, featuring his

Plato's Atlantis spring/summer 2010 collection and broadcast on the net in the fall of 2009, it was an altogether different and continually astonishing experience to see his clothes up close. I say clothes, which these creations are and which women have worn and will continue to wear, but they are, without question, works of art. One thing I know would probably have been impractical but which I wish the Met, with its ample (though not infinite) resources had arranged was for a model or two to wear some of the clothes, so that exhibit attendees could see them in motion, fitted onto and, in some cases, into, a body. The mannikins did suffice, but there were more than a few of his clothes, whether the

VOSS dress of spring/summer 2001, whose bodice comprised red-stained medical slides, with a skirt of dyed ostrich feathers, or the ensemble consisting of a skirt made of perforated balsa wood and a leather top that resembled a straightjacket, or the exquisite, faint-inducing

Sarabande gown, spring/summer 2007, of nude silk organza embroidered with real and cloth flowers, let alone all the medieval-to-BDSM-inspired accessories, that I would have loved to see someone--a woman, or a man able to fit them--wear and in-

habit,

embody them. In some cases they verged on being

unwearable, or at least required supreme concentration and effort, and betokened extreme discomfort, a physical experience so difficult and disorienting that it might alter one's sense of self; and yet, as

Daphne Guinness, Lady Gaga, Kate Moss, and his many other models and muses have proved, they were wearable.

McQueen (b. 1969),

who tragically took his own life at age 40 on February 11 of last year, demonstrated vision and skill from his earliest post-school collections. The exhibit, which artfully and successfully culls and mixes pieces from his vast store of masterpieces, shows this in the relatively pared-down, mostly monochromal early pieces that offer a short course in skillful tailoring, aesthetic refinement and innovation, and witty sexiness. His "Bumster" pants and skirt, in the

Highland Rape show of 1995-96, ride so low they barely top the buttocks or pelvic bone, yet manage not to appear vulgar but deliciously stylish, offer one example. Another would be the military motif worked to exciting ends in the

Joan show Autumn/Winter 1998-9 collection. Every piece in this show testifies to McQueen's technical adroitness, gifts for playing with differing and often difficult materials, colors, juxtaposition, and volume. But whether imagining tattered, post-shipwreck gowns or aluminum corsets or garbage-bag-like layered petticoats or pheasant-plumed sheaths, these pieces as a whole make clear that he achieved much more than just taking standard garments to exciting ends. As I slugged through the displays, I remembered some of the wilder shows he had staged, some provoking questions about his feelings towards women--there was the show titled

Highland Rape of course, and another that staged scenes in a madhouse, a clip of which was playing in one of the exhibit rooms, and then the clothes and shoes themselves at times seemed like they would induce as much physical pain as aesthetic pleasure if worn--but what I began to think about even more was that in a sense, his work over the years seemed to be pushing constantly in the direction not only of the "romantic," the term McQueen used to describe himself and that seemingly graced almost every wall of the show, along with "futuristic," or the fantastical and gothic, though those certainly are certainly key, as would the "queer" (did that term appear--I may have missed it), but especially of the

post/trans-human.

|

| Cephalopod |

Again and again, I kept keying on all those feathers, the robotic metallic bodices and carapaces, the heavy leathers, that wooden skirt, the blouse made of

mussels (!), the gown with the fake and real flowers, the prints--those extraordinary prints!--often symmetrical, that in that

Plato's Atlantis show featured insectlike and larval imagery abstracted into something else so beautifully strange it was hard to take your eye off it. Sublimity at points, certainly, for what other word could describe that "Jellyfish" ensemble from

Plato's Atlantis, with its dress, leggings and those dizzying marvelous "Armadillo" boots embroidered with iridescent enamel paillettes, giving the wearer and anyone viewing her an experience beyond anything we might fully take in in a single or multiple glances, and exceeding our capacity to fully comprehend what we were seeing--as human? A stunning woman-cephalopod, more likely. But that outfit also spoke to a kind of becoming-animal, or becoming-other, perhaps not so much in the

Deleuzian sense, but in a way auguring the transformations, technological/bionic, Darwinian and otherwise, that we certainly are undergoing as I type this, and which McQueen envisioned and attempted to push fashion fully towards. Western tradition, outside of mysticism, and magic, makes little space for this except as fantasy, as futurism, or via science. And McQueen would not be the first person, and certainly not the first gay man, to have dreamt of becoming someone or something that the

human could not encapsulate or limit. In the West, one acceptable way to address these possibilities other than through religion or mysticism or science, or which has brought them all together imaginatively, has been through art. In so many of these clothes-artworks, he presented artistic models for what the external forms of a post- or trans-human might look like.

|

| "Jellyfish" ensemble |

Of the "Jellyfish" ensemble and the entire show, McQueen himself said: "[This collection predicted a future in which] the ice cap would melt . . . the waters would rise and . . . life on earth would have to evolve in order to live beneath the sea once more or perish. Humanity [would] go back to the place from whence it came." Climate crisis--yes. But instead of death, or perhaps through the horror preceding it and the transfiguration after, we get something else, a glimpse of adaptation and the beauty that might result. These ensembles, like the

VOSS dress that births feathers, betoken a point of view that fascinates me to no end. Whereas other designers (and artists) aim to address the zeitgeist or shape it, or create clothes that flatter women or torment them or some mean between (or allow misogyny to take fabric form), or sew pieces that fly off racks at the highest end stores or the lowest or all, or mine the history of fashion and art and everything else to come up with something to fill a runway, or riff off the world around or inside them, or explore philosophical and aesthetic pathways that lead through a dress or pantsuit, or simply follow the leader, these clothes say over and over that McQueen, who was given to all of the above, also kept imagining, especially from the 2000 collections on, what might exist

after the human, which is to say, the feminine and masculine, the fashionable and clothing and fashion itself, after art: What then? And his merware, his avian extravaganzas, his floral and cephalopodic artifacts, offer some clues and answers.

|

| My notebook drawings of Savage Beauty |

|

| Dress, Horn of Plenty |

The Romantics not only extolled the relationship between art and nature, but saw the former often as a form of the latter. This certainly factors into McQueen's view, but he went further, melding, in real time, the former and latter, in the process rethinking the two, offering a series of fusions and transformations, to then be realized--borne and born, carried and carried off--by intrepid models and later by women lucky and wealthy enough to be able to afford, let alone wear his clothes. This was not simply clever futurism, but something much more far-reaching. I thought of this as I viewed his sumptuous, almost unbelievably beautiful and wrought--perhaps overwrought--posthumous collection, the

Horn of Plenty fall/winter 2010 line, first in real time in photos presented in the

New York Times in the spring of 2010, and then again, in select examples, in this show. One breathtaking dress, crafted of black-dyed duck feathers and eatured in the

Savage Beauty surpasses costumery and enters the realm of the

become-avian; in as much as it draws upon a range of references, from the literary (the raven, a Romantic symbol of death) to the historical (its lines evoke 1950s

haute couture), it exceeds them all. In fact many of the grave, sublime clothing-artworks in this final collection, which looked far back into the past while simultaneously well into the future, made me think that McQueen might have been thinking even more intently of a place beyond. Beyond human life--which is not to psychologize him, but to consider a possible philosophical perspective--or the constraints of the human, that

au delà as French so ingenously puts it reachable only by the here in which he achieved but also suffered so much.

There is one dress that I have looked at again and again, both online and in this show, that seems almost like a vision drawn from a place beyond, akin to one imagined centuries ago by

Aristophanes in his play

The Birds, but in this quite different

Cloud Cuckoo Land, this dress would adorn the Queen or members of the exalted court--for there is nothing democratic or parliamentary about most of these clothes, I must admit--the Bird-women or Women-birds or Bird-people, and you could imagine similar garments for the king, or androgynous/trans royal as well. It is costumey and yet not. I think McQueen was giving us glimpses of post-ness and trans-ness all along, but especially by the late 1990s, and by these final collections, as he said, "There is no way back for me now. I am going to take you on journeys you’ve never dreamed were possible," (

WWD, February 12, 2010); but also: "It is important to look at death because it is a part of life. It is a sad thing, melancholy but romantic at the same time. It is the end of a cycle—everything has to end. The cycle of life is positive because it gives room for new things." (

Drapers, February 20, 2010). He had already begun to give us those new things, and a few of them, thankfully for all who were able to see this show, were on display here.