About a year and a half ago, I thought of saying goodbye to this blog. It wasn't the first time, though. I'd considered doing this even further back, perhaps after the first year and a half of blogging, which would have been around late 2006. At that time I was still receiving a trickle of comments and the occasional hate post (based, if I recall correctly, on my epithet for George W. Bush, the "warrantless wiretapper"), as well as a small bombardment of spam, but I'd begun to feel like I not only was running out of things to say, but that I was unable because of work and life demands to remain timely, that I was mainly writing them for myself and that perhaps that wasn't enough to keep my commitment to this site. This issues very well could still be the case, but I do know that people read or at least skim this blog from time to time, be it friends old and new, students and colleagues, people referenced on the site, or even, as I learned, perhaps in 2009, people writing dissertations who have cited J's Theater in their arguments, and even, I'm told, at their defenses. (I kid you readers not, and my scholarly colleague who politely told me of one such case was not amused!) And though comments are rare, I have come to terms with the fact that I enjoy posting here, when I can, and that sometimes the posts resonate beyond this seeming echo chamber in which I cast them.

I say this as a prelude to commenting on Neil Strauss's recent Wall Street Journal article "The Insidious Evils of 'Like' Culture," which ravels one strand from Jaron Lanier's You Are Not a Gadget: A Manifesto (a book he doesn't mention) and similar works (M. Jodi Dean, Nicholas Carr, etc.) and builds an argument around it. The argument: the "like" feature, so prominent on Facebook and increasingly all over the web, is molding what we write and who we are online--and perhaps who we are and become. In order to curry "likes" and provoke "RTs" (retweets), we're performing and conforming, rather than just being ourselves. (You can block it, of course, but that's not Strauss's point....)

I would not be the first one to point out that in virtual space as in any other who we are is always a performance, that we already are shaping ourselves in various ways wherever we are, based on various contexts, that there is no pure or ideal self that is not at some point affected by the performative and all it entails. In fact this lies at the heart of any number of contemporary fields of critical and scholarly inquiry. That isn't to say that I'm completely disagreeing with Strauss, for I do believe that--and he doesn't mention the economics of the net and web, but Lanier and many others do--he's right on a certain level, and I find the "like" aspect of Facebook one of the most maddening, but I also feel that he doesn't address the facdt that there're benefits if you can conform and commodify yourself in certain ways. Wittier, shorter posts go over better than drier, longer ones, but single-issue blogs and Twitter feeds and Facebook pages probably attract more adherents than eclectic ones. The more personal you are, the more people will be interested, especially if there's a nice serving of (melo)drama tossed into the mix. Sex goes over better than its absense. If you're criticizing an unpopular president (Bush) vs. one whose still fairly popular and whom people expect you to extol (Barack Obama)....

For Strauss it's both a social and psychological issue. People want and need community, they want and need affirmation and attention...and above all approval, so they--we--are increasingly tailoring ourselves to provoke and be able to cull those "likes," instead of writing or tweeting whatever we--or Strauss and others--think to be "our true selves." Again, I'm not so sure about this "true selves" bit, though. But I get his point. C and I were even joking about this "like" mania a while ago, even using the term as a form of punctuation on the phone, to uproarious laughter. (It's been replaced with, among other things, "Yeezy taught me," but that's another matter.) Strauss mentions Google's new entry for its ++ service, those +1s that I, as someone publishing the blog via Google, now see at the bottom of these posts. As I wrote in my review of Lanier's book, he urges people to create in ways that cannot be subsumed within or reduced to forms meriting a simple (and simplistic) "like," which Strauss echoes, saying:

He even goes so far as to urge no comments on his post and certainly no "likes," though his employer, tracking page traffic, surely wants some. So I've violated his challenge, and will say that I "liked" his article. But believe me, I didn't click that button on his page nor comment.

(((

Cy Twombly (1928-2011) is no longer with us, I learned this evening from the New York Times. He had been suffering from cancer for the last several years, and passed away in Rome, where he has lived for most of each year since 1957. He is a major figure in the narrative of 20th century American and global art, but not without lingering controversy. His paintings grabbed me from the first time I saw them, their seeming artlessness suggesting the very inverse, depths that it would take many hours of looking to parse, their almost throwaway charm marking another kind of beauty, or possibility of the beautiful, particularly in the moment and aftermath of sensory engagement. I wrote in response to a friend's email about his death, referring to without mentioning the specific passages in the obituary:

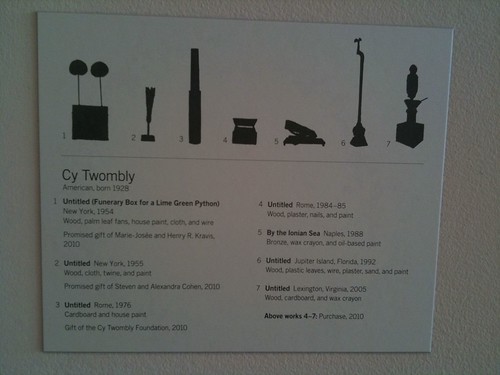

Here are those photos of his sculptures; I was permitted to photograph them but not Alÿs's work (not that that stopped me):

I say this as a prelude to commenting on Neil Strauss's recent Wall Street Journal article "The Insidious Evils of 'Like' Culture," which ravels one strand from Jaron Lanier's You Are Not a Gadget: A Manifesto (a book he doesn't mention) and similar works (M. Jodi Dean, Nicholas Carr, etc.) and builds an argument around it. The argument: the "like" feature, so prominent on Facebook and increasingly all over the web, is molding what we write and who we are online--and perhaps who we are and become. In order to curry "likes" and provoke "RTs" (retweets), we're performing and conforming, rather than just being ourselves. (You can block it, of course, but that's not Strauss's point....)

I would not be the first one to point out that in virtual space as in any other who we are is always a performance, that we already are shaping ourselves in various ways wherever we are, based on various contexts, that there is no pure or ideal self that is not at some point affected by the performative and all it entails. In fact this lies at the heart of any number of contemporary fields of critical and scholarly inquiry. That isn't to say that I'm completely disagreeing with Strauss, for I do believe that--and he doesn't mention the economics of the net and web, but Lanier and many others do--he's right on a certain level, and I find the "like" aspect of Facebook one of the most maddening, but I also feel that he doesn't address the facdt that there're benefits if you can conform and commodify yourself in certain ways. Wittier, shorter posts go over better than drier, longer ones, but single-issue blogs and Twitter feeds and Facebook pages probably attract more adherents than eclectic ones. The more personal you are, the more people will be interested, especially if there's a nice serving of (melo)drama tossed into the mix. Sex goes over better than its absense. If you're criticizing an unpopular president (Bush) vs. one whose still fairly popular and whom people expect you to extol (Barack Obama)....

For Strauss it's both a social and psychological issue. People want and need community, they want and need affirmation and attention...and above all approval, so they--we--are increasingly tailoring ourselves to provoke and be able to cull those "likes," instead of writing or tweeting whatever we--or Strauss and others--think to be "our true selves." Again, I'm not so sure about this "true selves" bit, though. But I get his point. C and I were even joking about this "like" mania a while ago, even using the term as a form of punctuation on the phone, to uproarious laughter. (It's been replaced with, among other things, "Yeezy taught me," but that's another matter.) Strauss mentions Google's new entry for its ++ service, those +1s that I, as someone publishing the blog via Google, now see at the bottom of these posts. As I wrote in my review of Lanier's book, he urges people to create in ways that cannot be subsumed within or reduced to forms meriting a simple (and simplistic) "like," which Strauss echoes, saying:

So let's rise up against the tyranny of the "like" button. Share what makes you different from everyone else, not what makes you exactly the same. Write about what's important to you, not what you think everyone else wants to hear. Form your own opinions of something you're reading, rather than looking at the feedback for cues about what to think. And, unless you truly believe that microblogging is your art form, don't waste your time in pursuit of a quick fix of self-esteem and start focusing on your true passions.

He even goes so far as to urge no comments on his post and certainly no "likes," though his employer, tracking page traffic, surely wants some. So I've violated his challenge, and will say that I "liked" his article. But believe me, I didn't click that button on his page nor comment.

(((

Cy Twombly (1928-2011) is no longer with us, I learned this evening from the New York Times. He had been suffering from cancer for the last several years, and passed away in Rome, where he has lived for most of each year since 1957. He is a major figure in the narrative of 20th century American and global art, but not without lingering controversy. His paintings grabbed me from the first time I saw them, their seeming artlessness suggesting the very inverse, depths that it would take many hours of looking to parse, their almost throwaway charm marking another kind of beauty, or possibility of the beautiful, particularly in the moment and aftermath of sensory engagement. I wrote in response to a friend's email about his death, referring to without mentioning the specific passages in the obituary:

Quite a loss. I like his attitude about his work, too. Also that he he was able to live long enough to see it come back into fashion and then to be recognized as central to the narrative of the art of his and our time. Of course it helps to have some wherewithal and connections, to be able to make your work, and to have critical champions, peers and those who don't know you from Eve. And to be able to plug into existing belief systems that people cherish, so that you don't have to continually explain what you're doing, unless you have champions who're willing to keep up with you all the way through. So many don't. But the work speaks for itself. The later pieces are gorgeous, so full of life, so redolent of what art can do in speaking to and creating life and reality, while also aware of Thanatos. I also of course like that he was queer, as primly and Victorianly as the NY Times stated it. Lastly, it's kind of resonant for me that I just snapped photos of his sculptures when my friend Jerry W and I went to MoMa last week, primarily to see the Francis Alÿs show. That was so slick; Twombly felt like a gift from another world. RIP.

Here are those photos of his sculptures; I was permitted to photograph them but not Alÿs's work (not that that stopped me):

Legend for the Twombly sculptures

In foreground, "Untitled (Funerary Box for a Lime Green Python)," New York, 1954

Foreground, "Untitled," Lexington, Virginia, 2005

In foreground, "By the Ionian Sea," Naples, 1988.

(((

A concept that enthralls that I haven't read a lot about but I'm sure someone is exploring or has already exhaustively looked at is geosynchrony*, which is the name I give (geo = space, place + syn = together + chronos = time) to being in the same place and space and time as someone else, sometimes over long periods, but seeing the same people all the time, perhaps never coming into contact with them or only doing so once or twice. In Care Crosses the River (translated by Paul Fleming; Stanford University Press, 2010), I believe, Hans Blumenberg recounts one of my favorite stories evoking this concept, noting that although Marcel Proust and James Joyce lived in Paris at the same time for a number of years, they reportedly only once encountered each other directly, when in May 1922 they shared a cab, with Sydney and Violet Schiff, after a dinner to honor a Stravinsky-Diaghilev Ballet Russe performance. (Can you imagine Proust and Joyce together in a cab?) Blumenberg recounts, much like the one I link to above, what occurred, which is to say, Proust, who had not arrived to the dinner until 2 or 3 chattered on, while an inebriated and smoking Joyce was silent, and the cab ride was over before you could say either À la recherche du temps perdu or Finnegans Wake.

I was thinking of this on a much more banal level, though, as I was reviewing some recent photos: one, from last week, was taken on June 29, 2011, in Bryant Park, as I was leaving the New York Public Library and people waiting to see that evenings film were clustering around the lawn to stake out their spots and set up their blankets and personal effects. Now it turns out that on that evening, if I am reading the news reports correctly, a certain Glenn Beck attended the movie screening and encountered some resistance to his presence there. A young woman, Lindsay Piscitell, accidentally, in her account, knocked over a glass of white wine onto his blanket and apologized profusely, before and after a few people in the crowd expressed their disapproval of him, that was it. In his typical bombastic TV account, he was razzled repeatedly by "hateful people", and the young woman, whom he excoriated as "lost" and "arrogant," spilled wine on his wife. Who knows what really happened, though I'm inclined to take the young woman's account more seriously than Mr. Testeria, but, that said, I was thinking, somewhere, maybe, in that gaggle I photoed edging the grass stands the Beck, his wife and their bodyguard, and had I chosen for the first time ever to stay in the park and catch one of these free films, I very well might have been witness to this event as unfolded, as I can spot people around corners and through doors (even if I cannot remember names to save my life anymore), and could have recounted to any and all who would listen, echoing Ted Hughes' simple Birthday Letters statement, "I was there, I saw it." I do think I would have had enough maturity not even to need to suppress a banal heckle--or gentle chiding--at the very sight (and site) of this man, though, especially given his advocacy of so much that's wrong with this society, and his hatred of the very concept of the commons and public spaces like Bryant Park, which he, his wife and his bodyguard were able to enjoy like anyone else who'd gotten there on time and found a spot, as opposed to the privatized, corporatized spaces he shills for on his programs. But I would certainly have taken his photograph, and posted it here.

|

| The countdown to seating in Bryant Park on movie night, 6.29.11 |