|

The signs read, "Brazil is quilombo residents;

not one less quilombo" |

All over the Americas, when fugitive slaves had the opportunities to escape and set up maroon (marrons in French, cimarrones in Spanish, maròn/mawòn in Kreyol/creole, etc.) communities, beyond the administrative and military grasp of the settler-colonial and slave system, they did so. These communities took different forms in different parts of the hemisphere, but their legacies continue, sometimes in name (palenques in Spanish, maroon towns or free towns in English), sometimes in traces and foundations that are mostly forgotten but still inspire the descendants. In Brazil, these communities were often known as

quilombos, the most famous of which remains

Palmares, in the interior of the northeastern state of

Alagoas, north of

Bahia, established by a group of fugitive slaves and warriors led by the great

Imbangala (

Angola)-descended

Zumbi (1655-1695).

Quilombos, from the

Kimbundu word kilombo, dot rural areas far from the major metropoles across northern and northeastern Brazil. As anti-colonial and anti-imperial, black-centered zones of resistance, they were targets of the Portuguese and later Brazilian governments in the colonial period, and the state's administrative, bureaucratic, legal, social, and economic war against them has not relaxed in the 20th and 21st centuries. From attempts to seize title to quilombo land to

the murders of quilombolas (residents of the quilombos), these communities have had to engage in continual struggle to stay whole, and free. A ruralist coalition of lawmakers, some allied with agribusiness and other powerful interests, has repeatedly attempted to gain control of the increasingly valuable quilombo territory. In 2003, however, then-President

Luiz Inacio "Lula" da Silva signed a decree that expanded the quilombolas' rights to title and demarcated their land, empowering the residents to gain legal title in order to keep them.

Brazil's current president, the profoundly unpopular

Michel Temer, took office after a soft 2016 coup in which he and the Brazilian Congress impeached and ousted popularly elected president

Dilma Rousseff, Lula's successor, over technical budgeting violations. Temer subsequently began instituting a range of neoliberal policies, under the aegis of pro-market rhetoric, yet Brazil's economy has continued to sputter, and the once expanding lower middle class of the Lula years has increasingly tumbled back into poverty.

Among Temer's actions that threatened the quilombos was an order to suspend the titling process for the quilombos, which are supposedly protected by the Brazilian Constitution, until the Brazilian Supreme Court (

Supremo Tribunal Federal, or STF) could rule on the validity of the decree Lula signed, which the conservative Democratic Party challenged.

After over five years in court, an overwhelming majority of the justices voted, 10-1, to uphold the decree, finally leading the Democratic Party's leader, Senator

Agripino Maia, from the northeastern state of Rio Grande do Norte, to end his opposition. The STF ruling represents a major victory for the quilombo communities and Afro-Brazilians in general, as well as for indigenous Brazilians, who have seen their lands seized and rights threatened, and a significant defeat for the powerful conservative rural interests, and their allies, including

overtly racist, homophobic leading far-right presidential contender Jair Bolsonaro (of Rio de Janeiro state), who have strongly supported Temer.

As

Black Women of Brazil blog reported (translating a report

from the Brazilian media site iG):

Members of the National Coordination of Articulation of the Quilombola Rural Black Communities (Conaq) celebrated the [decision].”This is a first step in the recognition of the debt that the Brazilian State has with the quilombolas, as it also has with the natives,” said Denildo Rodrigues, a member of the association at the end of the trial.

Conaq was one of many associations engaged in lobbying the STF in voting. Among other actions, it organized the undersigned “Not one less quilombo”, which had more than 100 thousand signatures requesting the maintenance of Lula’s decree.

“There is no motive, reason or circumstance today for the policy of titling quilombos to be or remain paralyzed. What is expected now is for the public administration to continue and complete the regularization processes,” said Juliana de Paula Batista, a lawyer at the Socio-Environmental Institute, also involved in the case.

It would be foolhardy to believe that this successful ruling will completely halt outside interests' attempts to gain control of the quilombolas' land, but it does give them an even stronger legal foundation to defend themselves in the courts, even as they battle ongoing violence and other forms of predation.

* * *

Black Women of Brazil Blog (BWBB) is always a trove of current, informative news about Black Brazil. One recent article I enjoyed

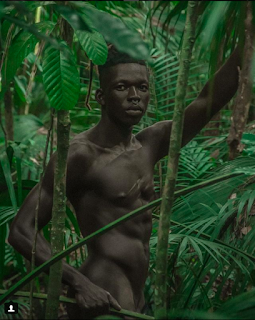

featured the work of Bahian-born and based photographer Thiago Borba, whose current project, "Black Is Beautiful," so appropriate for

Black History Month,

is featured at Revista Trip. On that site, in an article entitled "A coisa tá preta" (The thing is black), writer

Giulia Garcia discusses Borba's route to the project, which uses the respective English title and hashtag

Black is Beautiful (#BLVCKSBTFLL). After turning to photography in 2006 and studying in

Spain, Borba could find no jobs in Bahia, so he pursued a commercial career in

São Paulo to make ends meet.

In 2016, however, he reconnected with an earlier interest in exploring the topic of blackness in relation to beauty, still so fraught in Brazil, and started a photographic project entitled Paraíso Oculto (Hidden Paradise), melding images of black beauty in human form and natural landscapes. As BWBB regularly points out, contestations over beauty, and valorization of Eurocentric standards, constantly play out not only in interpersonal and intrafamilial spaces, but in the Brazilian public sphere. A number of spectacular, overtly racist incidents, involving denigration of Afrobrazilians' hair, features, color, style, and intelligence, have occurred over just the last year. One irony in all of this is that Afrobrazilians now constitute a numerical majority in the country, with sizable populations in Brazil's north, northeast and southeast.

He returned to Bahia from São Paulo last year, and began focusing on images of Afrobrazilians, particularly darker-skinned ones, who remain the most discriminated against in Brazil--not unlike in the US, where colorism within black communities, and within the larger US society, persists. Bahia is the traditional African heart of Brazil, with the highest percentage of self-identified black ("negro") and brown or mixed race ("pardo") residents, but hierarchies of color, class and ancestry exist there as well. As the Brazilian saying goes, "Quanto mais preto, mais preconceito sofre" (How much blacker you are, the more prejudice you suffer"), as true in Bahia as in pats of Brazil far smaller black populations, like

Santa Catarina, in the far south.

The new project centers "pretos retintos" (dark-skinned blacks), those people who are "mais preto," amid a range of hues; Borba draws his subjects mostly not from the ranks of models, but from his personal and broader social network. (Looking at the photos, though, any of these subjects could or

should model, and some, like

Vanderlei Nagô, clearly are modeling!) Borba began posting the images

on his Instagram page, and from there they gained wider notice and were selected for the state of Bahia's

Novembre Negro (Black November) campaign. (November 20 is

Dia da Conciência Negra, a holiday celebrated since the 1960s and officially established as a legal holiday in 2003 to honor the death, in 1695, of none other than

Zumbi do Palmares, mentioned above. In Bahia, the entire month is beginning to assume the cast of honoring black Brazilian history.)

According to BWBB and

Revista Trip, one of the images was even promoted on billboards, on buses and in the metro, among other public spaces. For Borba, this expanded reach was important in helping to amplify, in the eyes of minds of Afrobrazilians and

all Brazilians, the representation and representativeness of black people in Brazilian society. It is a battle we continue to fight in the US, in similar and different ways.

No comments:

Post a Comment