On April 25 of this year, Orham Pamuk, perhaps Turkey's leading fiction writer and a repeated target of governmental oppression, most recently when he was brought up on charges for having spoken openly of the Armenian genocide, delivered the inaugural PEN Arthur Miller Freedom to Write Lecture. The New York Review of Books printed it in the May 25, 2006 issue, and it's worth reading, so I link to it here.

On April 25 of this year, Orham Pamuk, perhaps Turkey's leading fiction writer and a repeated target of governmental oppression, most recently when he was brought up on charges for having spoken openly of the Armenian genocide, delivered the inaugural PEN Arthur Miller Freedom to Write Lecture. The New York Review of Books printed it in the May 25, 2006 issue, and it's worth reading, so I link to it here.A quote:

On (Appiah's?) Cosmopolitanism: Responses to Keguro

I always have difficulty expressing my political judgments in a clear, emphatic, and strong way—I feel pretentious, as if I'm saying things that are not quite true. This is because I know I cannot reduce my thoughts about life to the music of a single voice and a single point of view—I am, after all, a novelist, the kind of novelist who makes it his business to identify with all of his characters, especially the bad ones. Living as I do in a world where, in a very short time, someone who has been a victim of tyranny and oppression can suddenly become one of the oppressors, I know also that holding strong beliefs about the nature of things and people is itself a difficult enterprise. I do also believe that most of us entertain these contradictory thoughts simultaneously, in a spirit of good will and with the best of intentions. The pleasure of writing novels comes from exploring this peculiarly modern condition whereby people are forever contradicting their own minds. It is because our modern minds are so slippery that freedom of expression becomes so important: we need it to understand ourselves, our shady, contradictory, inner thoughts, and the pride and shame that I mentioned earlier.

In the comments section yesterday, Keguro posted one of his very concise and very provocative responses, so I thought I'd offer some responses. I can't and won't presume to speak for Kwame Anthony Appiah, or even recapitulate his rich and variegated arguments in a nuanced or extensive way, but I loved the issues Keguro posed, so here are my responses.

K: Appiah bothers me a lot. I am skeptical that shared cultural products necessarily have any connection to shared ethical values: that one sees cellphones in Ghana says little about the potential for one's ethical orientation.

J: What exactly bothers you about Appiah? Or Appiah's theorizations of cosmopolitanism. I'm curious to know what bothers. The New York Times Magazine/RSA e-journal article is problematic to me in part because I think Appiah is extrapolating from his particularized, glamorous experiences and views, presenting them (somewhat differently than he does in his philosophical work, which requires more careful theorization and abstraction) as the primary optics (and evidence) for viewing and understanding what's really a more complex phenomenon. The seeming equation of circulating consumerisms and ethics is problematic, but his larger point even in this piece has to do with authenticities and the individual's relation to his various allegiances, his location of self and selves, doesn't it? With cosmopolitanism(s) when very different kinds of contexts and experiences in and between worlds could constitute the basis for an argument on behalf of cosmopolitanism(s). That's why I think the larger defense of kinds and practices of cosmopolitanisms, which Appiah states at several points aren't fixed but fluid--he suggests that they're "challenges" rather than anything realized even by him so far--is interesting, and at times persuasive. So I wonder if the assumption that shared cultural products relates easily or directly to shared ethical values isn't a misreading of his arguments in both books; doesn't he suggest just the opposite, that the assumption of shared ethical values based on consumerist products or even a shared ideology is problematic for establishing one's ethical compass and values?

K: How does one become cosmopolitan? And what keeps one cosmopolitan?

J: These are great questions. My personal take would be that you could point to various routes, or to use Bourdieu's term, various habituses, by which you develop cosmopolitan identities and identifications (and disidentifications), acquire cosmopolitan affinities, and so on, and your particular experiences in the world, your allegiances, the norms and contexts of your experiences, etc., would all affect your sense of, performance of, practices of cosmopolitanism(s). If I were to distill to an extreme degree Appiah's complex arguments, a general shared experience of humanity--this abstracted, shared sense of being part of the human community beyond one's immediate group identifications and not relating solely to the kinds of commercial circulations he cites in the article--pulls (some of?) us towards cosmopolitanism. This lies at the heart of his philosophical exploration of the concept, but also leads to his critiques of universalisms--which some people (wrongly?) read cosmopolitanisms as--both of the local and, well, global kind.

K: Is globalization central to the formation of cosmopolitan identities (as Bruce Robbins and Pheng Cheah might suggest)?

J: I suppose Appiah would say that it's central, or rather , though it has had a profound effect on the formation of contemporary cosmopolitanisms and cosmopolitan identifications because of its role in the process of circulating ideologies, norms, goods, practices and so on. But in the second book, as briefly mentioned in the article, Appiah locates one origin of cosmopolitanism in the beliefs and practices of the Cynics, though I guess you could argue that the Greeks were proto-globalists, at least in terms of how far their technological achievements were able to take them. (I think you could also read the Phoenicians, the Egyptians, the Chinese, and others' circulatory histories as proto-globalizations.) I haven't read Sloterdijk in many years, but doesn't he come to different conclusions based on his reading of the Cynics?

K: Is cosmopolitanism necessarily opposed to national identities (as Gilroy might suggest and Laura Chrisman disagrees)? Is cosmopolitanism nothing more than moral obfuscation, cultural consumption and literacy taken as an ethical orientation (where, I think, Tim Brennan's early work ends)? (Okay, yes, I have many issues with the term and how academics use it.)

J: From what I gather, Appiah is suggesting that cosmopolitanism isn't necessarily opposed to national identities, but that they might be in tension with certain forms of cosmopolitanism. (This is the case for other kinds of identities as well.) I'm not that familiar with Brennan's work, so I plead ignorance, but I would imagine that Appiah interrogates the place and function of the moral pretty thoroughly, and doesn't link cosmopolitanism so easily or readily to cultural consumption and literacy, but to a more complex and as I said negotiated ethical orientation to one's lifeworld.

K: I wonder what happens to the quotidian in and within "cosmopolitanism."

J: This is a great question. I wonder what exactly the "quotidian" might be--since I'm thinking the "quotidian" could be many things (I know you're familiar with Michel de Certeau's work on this topic, among others), from its basic sense of the everyday, to a particular psychological, philosophical and/or sociological state or location, to an ideologically conditioned, ontological site of subjectivities, practices, etc...and if one were mapping one's own cosmopolitanisms, wouldn't the quotidian factor in(to) its many layers and aspects and be transformed by one's performance of them?

K: But now I'm simply testing out ideas contained in something I've been working on for a while--and will continue to do so for some time.

J: Please do post more on this (here and/or on your blog), and of course do critique my responses as fully as you can.

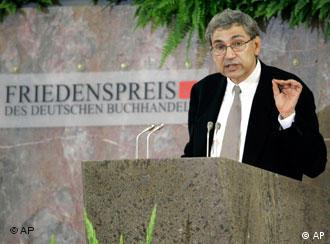

Random photo

Movie set, West 4th Street and 6th Avenue

No comments:

Post a Comment