After reading Brooklyn_in_Basquiat's recent post on the CDC figure among young Black MSMs in selected cities, it's clear to me that a number (but not all) of the issues I broached are still salient, though they probably deserve to be updated and treated more fully. But before I add new thoughts, I wanted to put out there what I'd been thinking four years ago, anachronisms and all (it precedes the Iraq War and other follies of the present administration, which probably would have gotten much more of a harsh airing), as the HIV/AIDS pandemic crossed the two-decade threshold.

20 YEARS AND COUNTING: HIV/AIDS AND THE STRUGGLE FOR OUR FUTURE*

As the entire world now knows, the terrorist atrocities of September 11, 2001 killed nearly 4,000 Americans and foreign nationals and injured many thousands more. The horrific suicide attacks razed New York’s landmark World Trade Center twin towers, as well as sixteen surrounding acres above and below ground, destroyed a fifth of the U.S. Pentagon, pushed the already faltering U.S. economy more deeply into recession, and severely breached our sense of domestic and international security. In response, U.S. President George W. Bush, with international allies, launched a global "war "against terrorism. The first stage of this campaign, labeled “Operation Just Cause” and fought by special forces and America’s Afghan proxies, has so far toppled the extremist Taliban government in Afghanistan, but also aims to capture or kill fundamentalist mastermind Osama Bin Laden and root out his Al Qaeda terrorist organization and its affiliated networks around the world. Bush and others have described the global anti-terrorism battle as one that may last for years.

2001 also, however, officially marked the 20th year of another worldwide struggle.** Its enormity, in fact, continues to elude us, because we still have neither fully assessed its nature and impact, nor expended the necessary resources—political, economic and social—even to get it under control. I am talking specifically about the AIDS pandemic. On the day that I began this article—December 1, 2001, World AIDS Day 2001—I was unfortunately able to write that, while accounting for evident successes in various parts of the globe, the challenges surrounding HIV (the human immunodeficiency virus) and the disease it causes, AIDS (acquired immune deficiency syndrome), remain daunting. Since the first cases of AIDS came to public attention in 1981, this disease—and the opportunistic infections that are its hallmark—has killed over 25 million people, 3 million of them alone in 2001, and AIDS has become the fourth leading international cause of death.

The United Nations, which convened a special session this past summer to address the global AIDS crisis, estimated that by the end of 2001 there would be 40 million people infected worldwide, with 5 million contracting HIV this year. Since AIDS is now spreading in some of the most populous nations on earth, such as China and India, as well as in some of the poorest and least stable, such as Haiti and Ukraine, the social, political and economic consequences of not aggressively grappling with every aspect of this pandemic could be devastating beyond our worst predictions.

The Good—The U.S.A.

Over the last decade, there have been many positive signs in the HIV/AIDS struggle, particularly in the United States. Nowadays neither HIV nor AIDS are or are viewed as the death sentences they were as recently as the early 1990s. While fear, ignorance and silence around HIV/AIDS have not disappeared, more Americans have access to basic information, in a range of media (pamphlets, books, videos, etc.) about how to avoid contracting HIV than 15 years ago. Condom advertising remains rare on television and even in magazines, but sexual prophylactics that would halt the spread of AIDS, such as male and female condoms, are in general widely available and reasonably economical. Since the late 1980s, in many bars, in a number of secondary schools and in most health clinics they are distributed free of charge.

Moreover, medical and public health officials have stressed the value of early and regular testing for HIV antibodies. It also probably is true that more people today know about the range of treatment options for AIDS than was true even ten years ago. Yet ignorance about how human seroconversion (contracting HIV) occurs, what behaviors are risky, the effectiveness of condoms, and how many of the most effective current medications work persists. As a January 25, 2002 article in Harvard Public Health Now details, even long-debunked ideas, such as that AIDS can be transmitted by mosquito bites or toilet seats, still unfortunately have currency.

Throughout the U.S., thousands of people with AIDS (PWAs) are able to consider their futures in terms of years and lifetimes instead of months, as had been the general case, in part because of the availability of powerful and effective antiretroviral (AVR) drug therapies, as well as improved diagnoses, protocols and overall treatment. At the same time, the public stigma of being HIV-positive—at least in terms of the larger American society—also has waned. (But the stigma has not vanished.) Organizations, such as the National Association of People with AIDS (NAPWA), and publications such as POZ directly advocate for PWAs, while many LGBT organizations, and some non-LGBT organizations offer AIDS-related components, programs and projects. Numerous white public figures, and a few major Black public figures, like NBA Hall of Famer Earvin “Magic” Johnson and tennis pioneer and sport scholar Arthur Ashe, have come out, so to speak, as PWAs, while others like dancer Bill T. Jones, have openly discussed their HIV-positive status and the health challenges they face. Outside celebrity circles, there are far more people of all races now openly living as seropositives or PWAs, which has helped to transform the view of HIV and AIDS, and to dispel for many the belief that the illness is restricted to a few groups, classes or races, particularly the handful of risk groups first enumerated in the early 1980s.

During his first term, President Ronald Reagan refused to publicly utter the word "AIDS,” an act emblematic in part of American society’s profound fear of and denial about the disease. George W. Bush, like his predecessor, Bill Clinton, however, has maintained the Office of National AIDS Policy to address HIV/AIDS issues at the federal level, and appointed Scott Evertz, an official with AIDS service experience to head the office. Bush has even maintained Clinton’s presidential AIDS advisory panel, though his executive director appointee, Patricia Funderburk Ware, has drawn criticism because of her advocacy of sexual abstinence to halt the spread of AIDS. The New York Blade noted in its January 18, 2002 edition that Bush has been “credited with promoting a newly created Global AIDS Trust Fund,” which will assist PWAs in developing countries. However, the newspaper noted that AIDS activists have criticized as “inadequate” the $200 million allocated to the fund so far.

At various levels of government there are HIV/AIDS task forces and programs, many of which work in tandem with community-based HIV/AIDS organizations on prevention and treatment programs. Today politicians across the ideological spectrum acknowledge the existence and public health implications of HIV/AIDS, and Congress (through the Americans with Disabilities Act) and many state legislatures have passed laws that punish discrimination against HIV-positive people and PWAs. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, U.S. spending during Fiscal Year 2000 on HIV/AIDS totaled $10.8 billion, with 19 percent going towards research, 8 percent towards prevention, 71 percent towards care and assistance, and 2 percent towards the global AIDS pandemic. Through a range of programs—Medicaid, Medicare, and the Ryan White CARE Act—as well as through state and local governments and community organizations, the Federal government underwrites HIV/AIDS coverage, care and education. AIDS, while still controversial, no longer is the unspeakable disease.

Scientists in the U.S. and abroad, in government-based, university and corporate research laboratories, continue to study and learn more about how HIV and AIDS function in relation to the human immune system, the environment and other illnesses. In the 20 years since the initial reports, the scientific community and industry have made tremendous strides in understanding HIV and AIDS and developing drugs to treat them, but a cure for the disease remains a dream. A great deal, though not all, of this information, has been disseminated to the general public through an array of government programs and private AIDS service and outreach organizations across the U.S., many founded by and targeted specifically to people of color. A considerable amount of the most up-to-date information on HIV/AIDS is available on the Internet, and has appeared in print media—though television still lags behind.

One cannot discuss these research advances without talking about one of the most important elements of HIV/AIDS treatment over the last half decade (1995-2000): the appearance in the mid 1990s of the powerful class of antiretroviral (AVR) drugs alongside the previous generation of AIDS drugs. Scientists and physicians have been able to devise effective medicinal combinations—or "cocktails"—to lower the viral count of HIV itself, boost or at least buttress the immune system, while also treating the often deadly opportunistic infections. Doctors and people with HIV/AIDS themselves have also gained and applied new knowledge other aspects of human health, from effective holistic and nutritional strategies, to the role of psychosocial factors and contexts, which they have been able to apply to HIV/AIDS treatment. All of these advances have led to a decline in the rate of deaths from AIDS from the highs of a decade ago.

Finally, many people have spent years working earnestly in the public health area on preventing the transmission of HIV, which is still the most effective way to halt its spread. In the process these public health officials and grassroots educators have enlightened millions about the realities of HIV/AIDS. Coupled with the advances in treatment and the increased knowledge about how HIV/AIDS operate, one result of this expansion of prevention efforts has been a decline in the rate of seroconversion among some groups.

The Not-So-Good—The U.S.A.

Amid these positive elements, however, fear and ignorance about HIV/AIDS endure, with the result that thousands of people continue to contract HIV, develop AIDS—and die. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Capital Briefing Series on HIV/AIDS, over 750,000 cases of AIDS have been reported in the U.S. from 1981-2000, and during that time 453,000 people have died. AIDS cases and deaths have been reported in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the U.S. territories, but ten states and territories—all of them with large populations of people of color (POC)—accounted for 72 percent (or nearly three-fourths) of all cases. Indeed, 10 metropolitan areas with populations over 500,000—and nearly all with large or majority POC populations—accounted for 43 percent of all AIDS cases from 1981-2000. Moreover, the South, the region of the country where the majority of Black Americans live, also had the greatest number of people living with AIDS and the greatest estimated number of new cases, followed by the Northeast, the West, and the Midwest.

As of 1998, although Blacks accounted for only 12 percent of the U.S. population, we accounted for 45 percent that year of all newly reported HIV/AIDS cases; in 1999, Blacks accounted for 47 percent (almost half) of newly reported HIV/AIDS cases. Over the last twenty years, we have accounted for 37 percent, or more than a third, of all reported AIDS cases. Per capita, Blacks constitute the majority of new AIDS cases and of Americans living with AIDS. In 1998, the AIDS case rate (cases per 100,000 population, which provide a measure of the impact of the epidemic standardized to population size) among Blacks was 9 times that of whites (84.7 per 100,000 vs. 9.9); among Black men, it was more than 7 times higher, while among Black women, the gap was 21 times higher. These are horrifying, wake-up-call numbers!

I should note, however, that the higher rates of incidence among Blacks may result in part from better identification of those who have seroconverted but in the past might not have been tested or identified. Given the improved treatment options, even if preventive efforts can lower the rates at which people are contracting HIV, there will still be more people living with the virus, and with AIDS. Thus, the prevalence (or total number of people living with AIDS, regardless of when they contracted it) levels require that we continue to stress safer sex options as a key element of prevention.

Looking specifically at men who have sex with men (MSMs), Lou Chibbaro, in a June 22, 2001 New York Blade article on recent Centers for Disease Control Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report findings, recounted that “4.4 percent of men between the ages of 23 and 29 who have sex with other men—and 14.7 percent of African-American men who have sex with men in this age group—were being infected annually with HIV in six large cities.” These figures mark the HIV “incidence,” that is, the number of people newly infected each year. Chibbaro noted that “[according to the CDC report] among this group, HIV incidence was 2.5 percent of white men who have sex with men and 3.5 percent among Latino men who have sex with men.” Thus, the incidence rate was thus about 5 times higher for Black MSMs than whites. Lastly, these findings updated a CDC study released in February 2001, which was part of an ongoing CDC research project on young MSMs in seven U.S. cities between 1998 and 2000. The earlier report, according to Chibbaro, focused on HIV "prevalence" among young MSMs. The February report showed that Black MSMs participating in the study had an HIV prevalence of 30 percent—i.e., almost third of the men in the study were HIV positive. CDC officials and AIDS activists considered this level "alarming and potentially catastrophic for [this] population group."

Yet as I noted above, not only Black MSMs are affected by HIV/AIDS: Black men having sex exclusively with women and Black women themselves also are battling HIV/AIDS, as are Black infants and younger people. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, in 1999, Black women accounted for 63% of newly reported AIDS cases among women. Sharon Cucinotta, in an February 2, 2001 article, "Women of Color With HIV/AIDS Virtually Invisible," on the Women's e news Website, writes that "The reality is worse than the statistics. [These] numbers represent only reported cases of women participating in the health care system."

A July 2001 New York Times article focused on the toll AIDS was taking on Black women throughout the rural South; among the article's sadder points was that even as seroconversion was rising among these sisters at an alarming rate, their access to health care their access to health care centers and professionals trained in women’s HIV/AIDS issues remained limited, with few changes in the near horizon. Black periodicals too have focused on the issues Black women with HIV and AIDS face: over the last few years, Essence, Blacklines and other publications have featured articles discussing the particular challenges facing Black women with AIDS, such as: poverty, sociocultural stigmas, lack of access to information and prevention programs, pre-existing health issues, and misdiagnosis and inadequate treatment.

Young African Americans of both sexes are unfortunately also still contracting HIV. In fact, according the Kaiser Family Foundation figures, young African-Americans represented more than half (57 percent) of new AIDS cases reported among 13-19 year olds in 1998. Again, these are tragic numbers, but they also are reversible. Princeton University psychology professor John Jemmott reported in a 1998 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association that results of the first HIV prevention study to compare the effects of educating teenagers about safe sex with the effects of educating them on abstinence suggested that “while both approaches affect sexual behavior in the short term, over the long term the safer-sex program not only increase[d] condom use but [might] decrease the frequency of sexual contact in some groups.” The study followed 659 inner-city African-American sixth- and seventh-graders, of whom 53 percent were female, for one year, and involved what Jemmott and his co-researchers called “interventions”: “combined group discussions, videos, games, brainstorming, experiential exercises, and skill-building exercises…[which] were designed to be educational, entertaining, and culturally sensitive.” Similar ongoing, targeted community and school-based interventions, promoting safe sex and prevention, geared to young people, from elementary school through high school, have a great potential for success and could have a profound effect in lowering transmission rates.

In terms of infants, while there have been treatment successes in halting seroconversion in utero and slowing or even stopping the progress of HIV in newborns, children unfortunately still continue to be born with HIV. In fact, some of the earliest waves of surviving AIDS infants are now in junior high and high school, facing not the typical variety of social and psychological pressures all teenagers must, but also dealing with specific PWA-related concerns. With regard to stopping or reversing seroconversion among newborns, it is imperative that drugs shown to be effective in this regard, such as AZT, be even more widely available at clinics and hospitals across the country.

This parade of bracing statistics, however, still does not convey HIV/AIDS' effects on Black families, Black communities, Black people—our future. To give just one example, almost an entire cohort of Black gay male writers was wiped out in the 1980s and 1990s by HIV/AIDs, leaving a breach in one of the groups perhaps best equipped to tell the stories of this disease. Parents have lost multiple sons (and daughters) to AIDS, while the worst period of AIDS deaths witnessed a terrible rise in the number of children who lost a parent or were completely orphaned by the disease. Yet as dreadful as these truths are, we still must tell them. More frank, honest and compelling accounts and narratives—in a range of media, but especially televisual and written forms—based on the best knowledge we have at hand, that openly discuss sexual issues rather than skirting around them, are necessary to convey the full impact of AIDS. In fact, such works might be the best way to foster and expand knowledge about HIV/AIDS and prevention. Recently, Lora Branch, Director of the Office of Lesbian and Gay Health at the Chicago Department of Public Health, in conjunction with director Sharon Zurek of Black Cat Productions, produced and distributed an engaging feature film entitled Kevin's Room, to be shown on television (it premiered on Chicago’s WPWR/UPN [Channel 50]), in bars, and at other venues. Many more such efforts, targeted at the entire spectrum of the Black community, as I noted, are needed.

The Global Picture

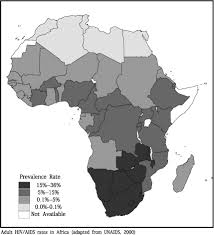

The global AIDS picture is grim. (For more information on the global pandemic, see the December U.N. magazine Choices.) Africa, our Motherland, leads the world in terms of annual AIDS case incidence and prevalence per capita (though new infections fell in the last year). In some African nations, the number of people with HIV/AIDS among the total population is as high as 5 percent and sixteen African countries have prevalence—i.e., people with HIV/AIDS--exceeding 10 percent among adults. In fact, AIDS has slain a generation or two in parts of Central and Southern Africa, and is wreaking havoc in multiple other ways. According to Michael Fleshman (in the U.N. journal Africa Recovery, quoted in the December 27, 2001 Toronto Globe and Mail), beside 17 million Africans felled by AIDS, we must add the 12 million orphans now left behind. Yet the emotional response to this tragic scenario has not been matched by the necessary resources or political will in many parts of Africa or outside the continent. As Salih Booker notes in the January 7-14, 2001 issue of The Nation,

Six months ago the world gathered in New York in a special session of the United Nations to adopt a global strategy to defeat AIDS, now acknowledged as the worst plague humankind has ever faced. The level of consensus offered hope that leaders might soon translate words into action. Kofi Annan won approval for a global fund with a target of $10 billion a year in additional resources. Yet on December 1, World Aids Day, the international community and the media gave only perfunctory notice to new UN estimates for 2001: 3 million more dead, 5 million more HIV infections, 40 million people now living with HIV/AIDS--28 million of them in Africa.

Several October 2002 New York Times articles have specifically examined the catastrophic situation in South Africa. Co-factors for the HIV/AIDS spread include widespread poverty and persistent social inequality, high crime and a particular crises of gang rapes, social stigma and denial, as well as an understandable, enduring suspicion of (white) health authorities. Yet most tragically, since the end of Nelson Mandela’s presidency South Africa has witnessed a severe lack of political leadership with regard to HIV/AIDS, particularly at the very top. President Thabo Mbeki’s repeated demurrals on AZT use among infants and his failure to accept international scientific findings about HIV and AIDS have both sent terrible signals to his Black constituents and had a deleterious effect on their health. It is not excessive to predict that unless he changes course soon and swiftly, his actions may have grave repercussions for his fellow Black South Africans for years to come, wiping out several generations and orphaning hundreds of thousands of children, thereby tearing apart the socioeconomic fabric of his people's lives.

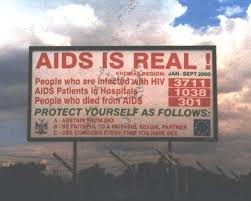

Yet despite the terrifying numbers across the continent, some African nations, like Uganda, have made strides in lower the rates of people contracting HIV, primarily through strong government and non-governmental prevention efforts, including dynamic grassroots education and condom distribution. These nations provide a useful example of low-cost, effective methods to combat the spread of HIV and manage AIDS cases in underdeveloped settings.

The Caribbean, one of the world’s centers of Black life and culture, has the second highest per capita infection levels in the world—2.2 percent of the adult population is infected. Only Africa, with an 8.4 percent prevalence level, exceeds the Caribbean. According to Lawrence K Altman in the New York Times (Nov. 29, 2001), “Haiti and the Bahamas have the highest rates, followed by Barbados and the Dominican Republic. In Central and South America, Belize, Guyana, Honduras, Panama and Suriname have rates of at least 1 percent.” Many of these countries not only face political and economic crises, but also lack the necessary educational and public health and hospital system infrastructures, which makes addressing the HIV/AIDS problem particularly difficult. Moreover, country-specific racial, class and cultural barriers, including homophobia, may also add to the challenges of HIV/AIDS in the Caribbean.

To this litany I must add recent figures of increasing incidence in southeast Asia (as well as in China and Central Europe. India, the second most population nation on earth, is believed to now have the largest total number of people with HIV/AIDS—perhaps anywhere between 3 to 7 million—though exact figures are unknown. To echo an earlier statement, the effect of the unchecked spread of AIDS upon Indian society, its economy and its political system, the world's largest democracy, could be disastrous—and the ripple effects would be felt across the globe.

If one examines the global Black HIV/AIDS situation, similar factors may explain the rates of new infections and the prevalence of the disease: all must be taken into account in future prevention and treatment programs. These factors include poverty and all the health problems related to it; lack of or inadequate access to quality medical care; the unaffordability and unavailability of HIV/AIDS drugs; misinformation about transmission and patterns of sexual activity; incidence and prevalence of other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs); and other behavioral differences (such as rape in South Africa). Outside the West, other factors may include virological differences in the strains of AIDS; differences in circumcision status; the presence of other infections (tuberculosis, etc.) that can increase HIV levels in the blood; and public policy differences among government authorities. With regard to the last factor, Brazil, which has the largest population of people of African descent outside Africa, has aggressively mounted prevention campaigns and effectively and widely distributed economically-produced AIDS medications, effectively lowering both the level of new infections and of deaths from AIDS over the last few years.

Few nations have even Brazil’s financial resources or health care infrastructure, let alone those of the United States. Yet if Uganda, like Brazil and Thailand, can make strides in dealing with HIV and AIDS, the United States certainly can and must augment international prevention and treatment. Our country can do this both by providing crucial logistical and financial support, and above all by making available desperately needed resources—lower cost medications, skilled physicians and trained public health officials, and tailored educational and prevention materials.

More Thoughts on HIV/AIDS Today in America

A number of critics, researchers and authors have noted the current, complex response to HIV and AIDS in the U.S. While surveys have shown that many Americans remain concerned about contracting HIV and developing AIDS and support research and prevention programs, surveys and anecdotal evidence also show that far too many people still approach the virus and disease with apathy, complacency and denial. As I noted above, misinformation about HIV transmission persists, even though an array of education material is more widely available than ever. Yet the sea of information may inadvertently and conversely foster indifference. What some AIDS educators and behavioral specialists have frequently pointed out is that scolding and badgering people about their sexual practices are ineffective long-term strategies, because they may spur defiance or indifference. Yet we also know that silence about unsafe sex is just as bad if not more dangerous. What leads people—especially MSMs, thus far the group hardest hit by HIV and AIDS—to participate in unsafe or seroconvertive sex requires continued study, but there is no doubt about the need for targeted, innovative and continuous prevention strategies, which make the dangers of AIDS and the importance of preventive activities vivid, persuasive and lasting. Approaches that are flexible enough take into account the broad range of factors that influence people's behavior may be the most effective.

One significant element in how people view HIV/AIDS today versus the late 1980s and early 1990s derives, as I noted above, from their portrayal in the media. Except on World AIDS Day, HIV/AIDS receive far less treatment outside the gay and lesbian press than previously, perhaps because of the fall off in sensationalism and spectacle (the high level of AIDS deaths, the ACT-UP protests, etc.), which the mainstream media thrives on. Today, news reports about the severity of the AIDS pandemic both within the U.S. and outside it are scarce; and especially rare today are serious and in-depth depictions in any media of the ongoing effects of AIDS in the U.S. Rarer still are Black PWAs depicted or featured in mass distributed magazines, on TV programs or in movies, except in cautionary, moralistic, often anonymous stories or plotlines. Certainly Earvin “Magic” Johnson makes for an excellent poster man in terms of AVR treatment successes (Cheryl L. Cole's perceptive essay on this topic appears in Delroy Constantine-Simms' 2001 collection, The Greatest Taboo: Homosexuality in Black Cultures), and I do not reproach the media for positively portraying life with HIV and AIDS. But not all PWAs are as healthy, photogenic or able to afford expensive treatment as Johnson or the many other attractive models that enliven the pharmaceutical ads.

Indeed, in a small non-scientific survey of prevention materials, periodicals, TV programs, and films, I came across only one instance (MTV’s Flipped) in which the potential negative physical, psychological and economic effects of an AIDS-related opportunistic illness were portrayed. All of these elements may factor into public complacency and misinformation about HIV and AIDS, leading some to believe the virus and disease are less serious problems—rather than more manageable--than in the past.

Some critics of current gay male sexual culture have pointed to the increasing visibility of barebacking (anal sex without condoms), or as it also is known, “raw dogging,” as a reason for the rise in seroconversion among some MSMs. Yet the apparent rise in barebacking as practice—in bathhouses, sex clubs, private parties (one Website lists 10-15 per night in cities across the nation), homes—and as a theme in various media, like the Internet and porno films, may be as much the result of greater recent attention on the topic rather than a real change in behavior. Some people also do still mistakenly believe that the penetrative partner—with or without a condom—cannot contract HIV. Other issues that must be addressed are the desire of some men (and people in general) for skin-on-skin contact, as a means of profoundly intimate sexual and spiritual connection; or the desire among some people for semen itself; or the sense that sex with condoms is not "natural," or restricts personal and political freedom, or constitutes an external imposition. There are other related arguments that have been and continue to be made. What is undeniable is that condomless penetrative sex (definitely anal and possibly oral) puts you at a greater risk for HIV and AIDS, whatever you call yourself, whoever is giving or receiving, whatever values you attribute to the sexual act, so on a purely preventive basis, stressing and reinforcing condom use, while taking into account these issues and arguments, must remain central to prevention efforts.

There are still too many Americans who view HIV/AIDS as a “gay” issue—the early narrative about the disease has taken root and has not been easily dispelled. Homophobia, both externalized and internalized, which plays into this mischaracterization, continues to be a problem in AIDS prevention. Related to this is the idea that some MSMs may feel that rejecting identification with homosexuals or as homo or bisexual somehow lowers their risk for contracting HIV. Other troublesome attitudes include the belief that only older men have HIV/AIDS; that people who appear outwardly “healthy” cannot transmit the virus; that adolescents and twenty-somethings are automatically HIV-free; and that the onus is on the HIV+ sexual partner to declare her or his serostatus. While this may be ethically indefensible, the burden is on both sexual partners to act as if safe sex is the best option. Women and men both have noted that even broaching the subject of condom use—let alone HIV status—can end a potential sexual experience, so they remain silent. In the new millennium, full inquiry should accompany full disclosure. Blame has no place in the equation.

There is the issue of testing for HIV, confidentiality and name reporting, and tracking of sexual partners. Some jurisdictions, such as New York State, have publicly instituted mandatory names reporting and partner notification systems to identify HIV-infected people as well as their sexual partners. This occasioned considerable outcry from AIDS activists, privacy advocates and civil rights and gay and lesbian organizations, but active intervention in shaping or turning back similar laws in other states. In Colorado and 26 other states (from New Jersey to Oregon) confidential named reporting occurs when people are tested for HIV. The CDC and several other organizations that support the civil rights of all HIV-infected persons support HIV infection reporting for public health purposes. All of these methods of identifying and tracking seropositive and potentially seropositive people are controversial; and given several high profile lapses of confidentiality in other areas of American life, questions about whether strict confidentiality and privacy can be maintained are critical. Although people's fear of finding out that they might be seropositive keeps most from getting tested, I would stress that there are numerous benefits to voluntary early and regular testing for HIV—and a voluntary, free or low-cost, accessible testing component, with strict anonymity and confidentiality, as well as appropriate counseling, should be part of all treatment and prevention efforts.

In the 1980s and 1990s, questions arose—and were aired by people such as the San Francisco-based psychologist Walt Odets--as to whether the needs of HIV-negative men (and women) were being adequately addressed. While this issue continues to some extent, one of the most positive signs in the last half-decade has been the dialogue between HIV+ men and women, PWAs, and those who are HIV-negative: out of such exchanges, which must continue and be expanded, more effective prevention materials and programs might develop and flower, because all the stakeholders are contributing their input.

Intravenous drug use involving sharing needles remains one of the primary modes of transmitting HIV, but needle exchange programs have been shown to be effective in lowering the possibility of transmission. When coupled with an outreach component, they also can provide AIDS educators and health officials with a vital link to at-risk individuals, HIV+ people and PWAs who may be experiencing other health problems that could effect their risk scenarios. Yet in many places across the U.S., need exchange programs remain controversial. Even Bill Clinton, whose response to the AIDS pandemic was commendable at times, refused to provide funding for needle exchange, which led to a 1998 vote of “no confidence” from the presidential AIDS advisory panel he had created.

Another trouble spot lies in the relationship between riskier sex, drug use and HIV seroconversion, an area that may receive less attention than it once did. But we also must continue to explore the role that ingesting any substances (from depressants such as alcohol through stimulants such as methamphetamines, etc.) that potentially lower immune resistance and dull one’s awareness and critical faculties during sexual activity play in the risk of seroconversion. It is a no brainer that proverbial “heat of the moment” slip-ups can increase when one is drunk, stoned or both, so factoring these scenarios into prevention efforts are crucial as well.

While AIDS in America has essentially become a chronic disease, we also should not forget several crucial points.

- The various drug combos do not work for everyone with HIV/AIDs;

- Their effectiveness over and beyond given time limits remains unknown;

- The effects of the drugs on some patients are more debilitating than AIDS itself, which may lead patients to go off therapy, thereby precipitating other problems;

- The effects of superinfection (that is, reinfection with HIV) are not fully known;

- Other diseases, such as lymphoma, HPV-associated cancers (anal, cervical), and hepatitis C are killing people who have successfully navigated the straits of AIDS

- Universal access to lifesaving drugs and protocols continues to be a problem.

Perhaps most importantly, drug-resistant strains of HIV/AIDS exist. According to a December 18, 2001 Reuters report, more than three-fourths (78 percent) of people with HIV in the U.S. may possess strains resistant to one or more of the available therapeutic drugs, meaning that no effective drugs may be available to treat them, so the AVR backup, so to speak, can no longer always be considered an option.

The funding picture for HIV research, prevention and treatment remains a question. AIDS activists have assailed the fact that Bush’s first proposed budget did not increase funding for the Ryan White CARE Act program; yet Congress added more Ryan White funds and Bush did not oppose the increase. Yet despite the recent federal outlays, Medicaid pays for the majority of AIDS treatment and care, yet the global recession and shifting Federal fiscal priorities and demands, coupled with calls by some leading Republicans for further budgetary cuts, may mean less money for HIV/AIDS. Right now, most states and local municipalities, which face their own budgetary restrictions, lack the resources to make up the difference. In the case of New York City, the national leader in total AIDS cases over the last 20 years, political and ideological battles between former mayor Rudy Giuliani and some AIDS service organizations led to problems in AIDS service delivery, despite several years of budget surpluses; now the City and state face the worst budget deficits in many years, which imperils necessary AIDS funding. But New York City is not unique is this regard.

Just as troubling is an intellectual backlash, expressed publicly by critics such as Norah Vincent on Salon.com, and held privately by unknown numbers of people, concerning behavior, culpability, and the contributions that non-HIV-infected people should be asked to make to fight the epidemic. Stated simply, Vincent has questioned whether adults, particularly gay men, should not know better 20 years into this pandemic about the causes of serotransmission and AIDS, and has wondered whether, if they refuse to practice safer sex, others should continue to provide funding? Of course, this is a grossly simplistic and disturbing argument by any measure, which hardly accounts for economic and social disparities that thousands of people face with regard to knowledge about HIV and serotransmission. But it and similar beliefs (particularly arising from libertarian concerns about public funding for AIDS and conservative issues about homosexuality and sexual behavior), if more widely expounded and held, could negatively affect future crucial funding.

Outside the U.S., particularly in the developing and underdeveloped world, the lack of funding is a critical issue, as it impacts every other aspect of the anti-AIDS efforts. The U.S., as well as other rich nations around the world, must therefore find the money and dig more deeply into its pockets to assist its less fortunate fellow nations in addressing the global AIDS pandemic. The Global AIDS Trust Fund, U.N. AIDS programs and similar efforts are crucial, and must be adequately funded to succeed.

Several of the largest insurance companies have begun efforts to reformulate their policies to stop paying for long-term illnesses by limiting options for deductibles, making them prohibitively expensive, or not insuring certain patients at all, all of which could directly impact PWAs. Also, the economic disruption caused by the terrorist atrocities and the recession, along with donors’ current focus on charities directly addressing the effects of September 11th, will probably mean that public and private monies for HIV/AIDS, like so many other worthwhile issues, will be scarce for at least the short term.

In all of the above cases, the impact is disparate for Black PWAs and for Blacks in general, who have less income, less information, less access to the best health care options, and a range of social and psychological stress factors that impact health care and treatment experiences.

Now Is the Time

This is, however, a particularly critical time, both domestically and globally, in terms of HIV/AIDS. Although people here and abroad continue to seroconvert and develop AIDS, at alarming rates among POC groups and the poor, America’s priorities 20 years after 1981 are not on HIV/AIDS, especially in this period of war, national defense and global economic uncertainty. This does not mean, however, that we should allow indifference or complacency to triumph.

Now is the time to stress a renewed global effort to address the AIDS pandemic, and enlist and engage indifferent or recalcitrant governments, such as South Africa, to ensure no backsliding from our own. Now is the time to redouble domestic and international funding for grass-roots and community-based, multi-pronged prevention and education programs. Now is the time to reinforce these efforts through by using the both government and marketplace mechanisms, and utilize the media to spread knowledge and information about HIV/AIDS. Now is the time to push for the necessary resources to underwrite continued research on HIV/AIDS as well advance the development and wide distribution of new medicines to manage (and perhaps cure) AIDS and related opportunistic infections. Now is the time to insure parity and equality, both within the U.S.A. and across the globe, with regard to economical treatment options—including lower-cost drug therapies and full access to physicians with expertise in HIV/AIDS. Now is the time.

A Cassandra-like tone may underline much of this article. Yet I believe that the repercussions if we as a Americans, as Black people, choose complacency or inaction over continued, concerted efforts to address HIV and AIDS, really could be far more disastrous, both here and abroad, than anything we have witnessed so far. There is no cure, so improved education, high-quality treatment, dynamic prevention and sustained vigilance must be paramount. This is a struggle we can better manage, and, with hope, manage to win.

*This article proceeds from the premise that HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus) is the central cause of AIDS (Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome). Although critics since the appearance of HIV/AIDS have questioned whether HIV seroconversion leads to AIDS, this article accepts the broad range of scientific findings that have established that it does.

**I use this metaphor despite the fact that some critics, like Susan Sontag, have suggested it is inadequate and incommensurate for theorizing about and discussing illness in general, and the HIV/AIDS pandemic in particular. It is quite common in popular discourse, however, and I am proceeding from that (perhaps faulty) starting point.

Copyright © John Keene, 2001, 2002.

I have been HIV positive since 1989, I got HIV from open heart surgery when I was 18 years old. March 2005 I was diagnosed AIDS status and started Truvada and Sustiva (my labs). Find out more about me HERE ;)

ReplyDeleteGreat blog I hope we can work to build a better health care system as we are in a major crisis and health insurance is a major aspect to many.

ReplyDelete