What are the origins of Memorial Day, during which we as a nation honor those who've fallen in wars past and current? I always thought I'd known, and would readily have stated it publicly if asked. Yale historian David Blight, however, enlightened me--and thousands of others, perhaps millions--with his article in today's New York Times, "Forgetting Why We Remember," on the holiday's origins and likely earliest celebration. It, as I have repeated several times on here about the Times's Disunion pieces, moved me mightily.

As it turns out, the first Memorial Day celebration probably took place in the South, amidst the ashes of the defeated Confederacy, in Charleston, South Carolina, ironically and poetically, as that was the political and cultural headquarters of the states' plantocracy, who pushed secession from the Union, and the vantage from which soldiers under General P. T. Beauregard first the shots at Fort Sumter, launching the war. The celebration occurred in, on and around a race track that the Confederates had transformed into a prison and eventual morgue for Union soldiers. Blight writes:

Blight goes on to note that after the processions and tributes, the blacks and whites then began picknicking--sharing food and drink, enjoying each others' companies--and watching military drills by the African-American regiments, including the famous 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment, one of the first official all-black Union regiment in the war, the subjects of Edward Zwick's 1989, Academy Award-winning film Glory. (At the top of the article is a detail from Augustus Saint-Gaudens' famous Robert Gould Shaw memorial, which sits at a corner of Boston Common, at Park and Beacon Streets, and which Robert Lowell memorialized in his famous poem "For the Union Dead." The second image is an 1890 lithograph by Kurz and Allison of the 1863 storming of Ft. Wagner in South Carolina, the battle at which Shaw died.)

This history somehow got lost to the wider world, though, interestingly enough to me, the Preservation Society of Charleston does mention it, noting it to be the first Memorial Day celebration, on their website at the link above. Blight does not tarry over the process by which this history has evanesced or its implications, though I would imagine that like so much of our national history, especially anything involving African Americans, cross-racial alliances, and so on, it has suffered both active and passive omission until, voilà, it has been waiting for someone to bring it to wider attention. It is, as I said, on the website above and perhaps on many more too. [I should note that while I have read a great many books of and on American history, I have never heard of this event, though historians very well may have written extensively about it. I have many times heard about the various early Northern and Southern commemorations of the war and those who died in it.] At any rate, as we go about our business today and on every memorial day hereafter, we might keep a kernel of this re-membering of the our polity, led by these brave freed people after the worst war US soil has ever known (and I hope will ever know), fastened to our memories.

+++

On a lighter note regarding the states, I was reading Huffington Post's Comedy page and chuckled at author Chuck Jury's "50 State Stereotypes in 2 Minutes" video, which is a promo for his new book of the same name. He's tagged some of the states perfectly, though with others it appears he just tossed out whatever he could think, anything he could think of, quickly. Cf. Indiana. (I also love that he probably filmed the entire 50 entries in California, but chose landscapes that mirrored (or not) those of the states he invokes.

As it turns out, the first Memorial Day celebration probably took place in the South, amidst the ashes of the defeated Confederacy, in Charleston, South Carolina, ironically and poetically, as that was the political and cultural headquarters of the states' plantocracy, who pushed secession from the Union, and the vantage from which soldiers under General P. T. Beauregard first the shots at Fort Sumter, launching the war. The celebration occurred in, on and around a race track that the Confederates had transformed into a prison and eventual morgue for Union soldiers. Blight writes:

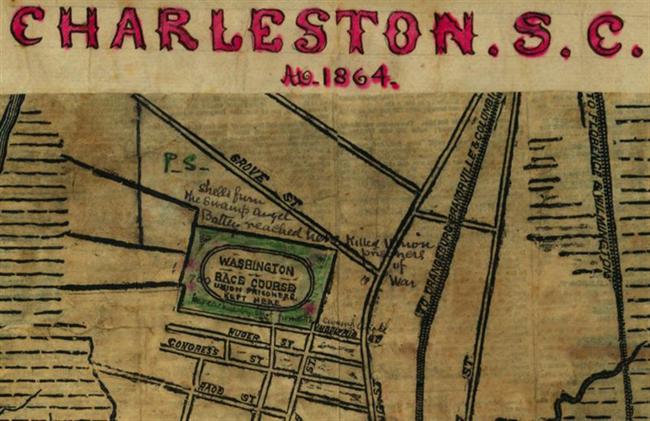

The largest of these events, forgotten until I had some extraordinary luck in an archive at Harvard, took place on May 1, 1865. During the final year of the war, the Confederates had converted the city’s [Charleston's] Washington Race Course and Jockey Club into an outdoor prison. Union captives were kept in horrible conditions in the interior of the track; at least 257 died of disease and were hastily buried in a mass grave behind the grandstand.Note for a second the presence of ritual here--the whitewashing of the fence, and the renaming of the race course, a sports site transformed in a site of horror, and now, a place of remembrance, grieving, and honor. (The 1864 map of the Washington Race Course above comes from the Preservation Society of Charleston's website.)

After the Confederate evacuation of Charleston black workmen went to the site, reburied the Union dead properly, and built a high fence around the cemetery. They whitewashed the fence and built an archway over an entrance on which they inscribed the words, “Martyrs of the Race Course.”

The symbolic power of this Low Country planter aristocracy’s bastion was not lost on the freedpeople, who then, in cooperation with white missionaries and teachers, staged a parade of 10,000 on the track. A New York Tribune correspondent witnessed the event, describing “a procession of friends and mourners as South Carolina and the United States never saw before.”Note here more significant elements: the cross-racial union to make the celebration possible, in defiance of the very grounds on which the Confederacy was founded; the presence of teachers, another countersignifier in relation to what African Americans had been subjected to under slavocracy's tenets; children in the forefront of the march, a recognition of their role as the future and vanguard, of the race and nation; the singing and evocation of abolitionist John Brown, a freedom fighter and pre-war martyr whose memory was well known to and not lost on these newly freed people; and then the freedmen followed by, not following, the Union troops, some of them African Americans, as Blight notes. Then come the celebrations of patriotism and, alongside them, religion.

The procession was led by 3,000 black schoolchildren carrying armloads of roses and singing the Union marching song “John Brown’s Body.” Several hundred black women followed with baskets of flowers, wreaths and crosses. Then came black men marching in cadence, followed by contingents of Union infantrymen. Within the cemetery enclosure a black children’s choir sang “We’ll Rally Around the Flag,” the “Star-Spangled Banner” and spirituals before a series of black ministers read from the Bible.

Blight goes on to note that after the processions and tributes, the blacks and whites then began picknicking--sharing food and drink, enjoying each others' companies--and watching military drills by the African-American regiments, including the famous 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment, one of the first official all-black Union regiment in the war, the subjects of Edward Zwick's 1989, Academy Award-winning film Glory. (At the top of the article is a detail from Augustus Saint-Gaudens' famous Robert Gould Shaw memorial, which sits at a corner of Boston Common, at Park and Beacon Streets, and which Robert Lowell memorialized in his famous poem "For the Union Dead." The second image is an 1890 lithograph by Kurz and Allison of the 1863 storming of Ft. Wagner in South Carolina, the battle at which Shaw died.)

|

| Black Union soldiers, US Civil War, from Civil War Academy |

+++

On a lighter note regarding the states, I was reading Huffington Post's Comedy page and chuckled at author Chuck Jury's "50 State Stereotypes in 2 Minutes" video, which is a promo for his new book of the same name. He's tagged some of the states perfectly, though with others it appears he just tossed out whatever he could think, anything he could think of, quickly. Cf. Indiana. (I also love that he probably filmed the entire 50 entries in California, but chose landscapes that mirrored (or not) those of the states he invokes.

Jury certainly has Illinois down, I'll give him that. (But is he talking about Governor Pat Quinn or Mayor Rahm Emanuel. Hmm.)

With a far different aim, last July I posted an animated tour of the 50 states, primarily for children to learn their years of entry into the United States. Of course I did not advertise it anywhere, so it has gotten about 10 viewers or something, but anyways, after the laughter above, check this out, with your little ones if they haven't already learned this information. It's quite rough, but then I'm no pro at this stuff. But it was fun to do!

No comments:

Post a Comment