Over the winter break I dropped by The Kitchen to check out artist Adam Pendleton's solo exhibit BAND. I've followed Pendleton's work for awhile, and have regretted having missed several earlier shows of his in Chicago, all word art pieces at the Rhona Hoffman Gallery--2007's "Rendered in Black and Rendered," 2005's "Gorilla, My Love," and 2004's "It's about memory"--so I beat a path to Chelsea to catch this one before it closed on December 23, 2010.

Curated by Rashida Bumbray, the Kitchen exhibition marked the US premiere of Pendleton's large-scale video installation and the final stage of a more extensive multi-platform exhibition, which debuted on September 17, 2009 at the Toronto International Film Festival and featured a rehearsal and live public concert by indie-postpunk band Deerhoof. A December 2009-January 2010 performance and reading in Amsterdam, featuring the first edit of Toronto event footage along with work-in-progress sequences based on texts directly drawn from Jean-Luc Godard's famous 1968 quasi-documentary, Sympathy for the Devil, such as ones by Eldridge Cleaver, along with more associatively linked works, by writers like Gertrude Stein, was programmed by and held at the Kunstverein/de Appel Arts Center.

Band reimagines film, replacing the Rolling Stones prepping and then playing their eponymous song with Deerhoof practicing and then performing the haunting "I Did Crimes for You" (from their new album Deerhoof vs. Evil, Polyvinyl, 2011) in refracted, multiscreen, asynchronous form. Pendleton's film also retains more than just the spirit of Godard's overtly radical, overtly politicized aesthetics in Sympathy, which juxtaposes imagined scenes of Black radicalism, informed by the work of Cleaver, Amiri Baraka and others with a performance by Godard's then-wife Anne Wiazemsky, as "Eve Democracy," an icon of Euro-American leftist politics and poetics. Band does also carry forward in formal and content terms this aspect of Godard's film. In post-production, Pendleton and editor Deco Dawson interlaced the Deerhoof footage with audio from a short documentary film entitled Teddy, created, to quote The Kitchen's press release, "as part of the Social Seminar, a multi-media training series developed by the National Institute of Mental Health with the U.S. Office of Education." Teddy, directed by Richard Wells and edited by Andrew Stein, portrayed a day in the life of a politically active 17-year-old black man; in Band Pendleton paired the audio track with clips from a late 1960s LA Police Department raid on a Black Panther office.

It's been a while since I've seen Godard's film, but Pendleton distills its essence here; both works link the rehearsal sessions of a band with arguably progressive politics, sympathies, and aesthetics, then and now, with revolutionary imagery, as a means of reflection on the political valences of popular music, and institutionally validated cultural production and performance themselves. Yet the differences in social, political, economic, and cultural contexts between the two films create very different responses for the viewer. While Godard's film, for all its faults feels like a revolutionary by a self-consciously white artist striving to imagine a new way of engaging the political through art, Pendleton's admittedly visually striking film comes off as one component of a well-made, formally innovative institutional product by an aesthetically revolutionary un-self-consciously black artist, and, I'm almost loath to say this because I am a huge admirer of Pendleton's, it almost approximates a skillfully effective commercial.

It's been a while since I've seen Godard's film, but Pendleton distills its essence here; both works link the rehearsal sessions of a band with arguably progressive politics, sympathies, and aesthetics, then and now, with revolutionary imagery, as a means of reflection on the political valences of popular music, and institutionally validated cultural production and performance themselves. Yet the differences in social, political, economic, and cultural contexts between the two films create very different responses for the viewer. While Godard's film, for all its faults feels like a revolutionary by a self-consciously white artist striving to imagine a new way of engaging the political through art, Pendleton's admittedly visually striking film comes off as one component of a well-made, formally innovative institutional product by an aesthetically revolutionary un-self-consciously black artist, and, I'm almost loath to say this because I am a huge admirer of Pendleton's, it almost approximates a skillfully effective commercial.

Perhaps that's unavoidable in this era when art and capital have almost completely made their peace; artists of all ages shuttle through schools, programs and residencies created by the very institutions and sponsored by the very industries that they once critiqued and challenged; and few bands possess the combination of popularity and street cred that a group like the Rolling Stones did in their heyday. Moreover, Pendleton's goal obviously isn't Godard's. Whereas Godard was trying both to ideologically and aesthetically remake and undermine cinema as it had developed up till his time, Pendleton's work has struck me as increasingly virtuoso contributions to various strands of artmaking that have become mainstream since Sympathy for the Devil. I don't criticize this, because it's worthy of praise.

I nevertheless hope that Pendleton will employ his multiple gifts down the road in the service of something radical and revolutionary. Though it was not his goal I wondered what might a creative reading of Godard's film look like that paired a politically radical musicians like Michael Franti or a group like Dead Prez, say, with footage from the anti-war protests of 2002 and 2003, or from the Iraq War or Abu Ghraib, or from Guantánamo, open wounds that continue to fester? Or, perhaps even more directly related to the politics and themes articulated by the Black Panthers, old and new, who directly challenged state power, and racism and white supremacy, what about scenes from any of the maximum security prisons around the country, especially those engaging in what amounts to torture of black and brown peoples via prolonged isolation and depravation, among the many other tragedies occurring with their heavily guarded walls?

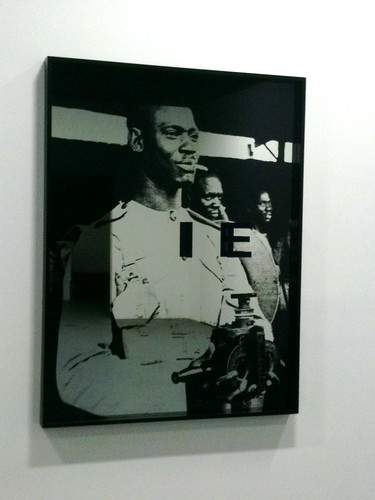

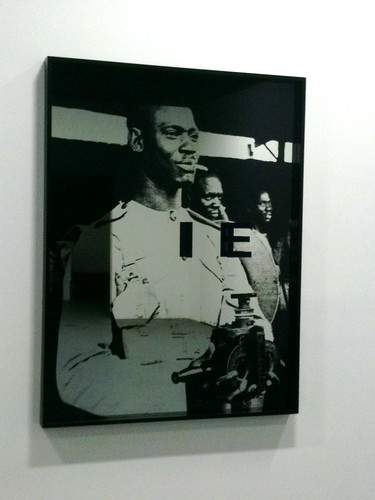

The exhibit also included featured new works from Pendleton’s ongoing System of Display (2008-) series, which, like the film, demonstrated considerable plastic facility. These wall-mounted assemblages sample a range of references, such as from the scholar Aby Warburg’s archive of late 19th Century American West photographs, which Pendleton juxtaposes with word fragments drawn from an associative list. Formally, the assemblages consist of silkscreens of the images and letters onto mirrors and clear glass, placing them within boxes, allowing Pendleton to create a fresh mode of display and presentation that delinks the visual imagery from their prior historical and material contexts and the words form their usual semantic and signifying relations. Individually and together they merit repeated viewing, so I hope to see some more of them soon at another Pendleton exhibit.

Curated by Rashida Bumbray, the Kitchen exhibition marked the US premiere of Pendleton's large-scale video installation and the final stage of a more extensive multi-platform exhibition, which debuted on September 17, 2009 at the Toronto International Film Festival and featured a rehearsal and live public concert by indie-postpunk band Deerhoof. A December 2009-January 2010 performance and reading in Amsterdam, featuring the first edit of Toronto event footage along with work-in-progress sequences based on texts directly drawn from Jean-Luc Godard's famous 1968 quasi-documentary, Sympathy for the Devil, such as ones by Eldridge Cleaver, along with more associatively linked works, by writers like Gertrude Stein, was programmed by and held at the Kunstverein/de Appel Arts Center.

Band reimagines film, replacing the Rolling Stones prepping and then playing their eponymous song with Deerhoof practicing and then performing the haunting "I Did Crimes for You" (from their new album Deerhoof vs. Evil, Polyvinyl, 2011) in refracted, multiscreen, asynchronous form. Pendleton's film also retains more than just the spirit of Godard's overtly radical, overtly politicized aesthetics in Sympathy, which juxtaposes imagined scenes of Black radicalism, informed by the work of Cleaver, Amiri Baraka and others with a performance by Godard's then-wife Anne Wiazemsky, as "Eve Democracy," an icon of Euro-American leftist politics and poetics. Band does also carry forward in formal and content terms this aspect of Godard's film. In post-production, Pendleton and editor Deco Dawson interlaced the Deerhoof footage with audio from a short documentary film entitled Teddy, created, to quote The Kitchen's press release, "as part of the Social Seminar, a multi-media training series developed by the National Institute of Mental Health with the U.S. Office of Education." Teddy, directed by Richard Wells and edited by Andrew Stein, portrayed a day in the life of a politically active 17-year-old black man; in Band Pendleton paired the audio track with clips from a late 1960s LA Police Department raid on a Black Panther office.

It's been a while since I've seen Godard's film, but Pendleton distills its essence here; both works link the rehearsal sessions of a band with arguably progressive politics, sympathies, and aesthetics, then and now, with revolutionary imagery, as a means of reflection on the political valences of popular music, and institutionally validated cultural production and performance themselves. Yet the differences in social, political, economic, and cultural contexts between the two films create very different responses for the viewer. While Godard's film, for all its faults feels like a revolutionary by a self-consciously white artist striving to imagine a new way of engaging the political through art, Pendleton's admittedly visually striking film comes off as one component of a well-made, formally innovative institutional product by an aesthetically revolutionary un-self-consciously black artist, and, I'm almost loath to say this because I am a huge admirer of Pendleton's, it almost approximates a skillfully effective commercial.

It's been a while since I've seen Godard's film, but Pendleton distills its essence here; both works link the rehearsal sessions of a band with arguably progressive politics, sympathies, and aesthetics, then and now, with revolutionary imagery, as a means of reflection on the political valences of popular music, and institutionally validated cultural production and performance themselves. Yet the differences in social, political, economic, and cultural contexts between the two films create very different responses for the viewer. While Godard's film, for all its faults feels like a revolutionary by a self-consciously white artist striving to imagine a new way of engaging the political through art, Pendleton's admittedly visually striking film comes off as one component of a well-made, formally innovative institutional product by an aesthetically revolutionary un-self-consciously black artist, and, I'm almost loath to say this because I am a huge admirer of Pendleton's, it almost approximates a skillfully effective commercial.

Perhaps that's unavoidable in this era when art and capital have almost completely made their peace; artists of all ages shuttle through schools, programs and residencies created by the very institutions and sponsored by the very industries that they once critiqued and challenged; and few bands possess the combination of popularity and street cred that a group like the Rolling Stones did in their heyday. Moreover, Pendleton's goal obviously isn't Godard's. Whereas Godard was trying both to ideologically and aesthetically remake and undermine cinema as it had developed up till his time, Pendleton's work has struck me as increasingly virtuoso contributions to various strands of artmaking that have become mainstream since Sympathy for the Devil. I don't criticize this, because it's worthy of praise.

I nevertheless hope that Pendleton will employ his multiple gifts down the road in the service of something radical and revolutionary. Though it was not his goal I wondered what might a creative reading of Godard's film look like that paired a politically radical musicians like Michael Franti or a group like Dead Prez, say, with footage from the anti-war protests of 2002 and 2003, or from the Iraq War or Abu Ghraib, or from Guantánamo, open wounds that continue to fester? Or, perhaps even more directly related to the politics and themes articulated by the Black Panthers, old and new, who directly challenged state power, and racism and white supremacy, what about scenes from any of the maximum security prisons around the country, especially those engaging in what amounts to torture of black and brown peoples via prolonged isolation and depravation, among the many other tragedies occurring with their heavily guarded walls?

The exhibit also included featured new works from Pendleton’s ongoing System of Display (2008-) series, which, like the film, demonstrated considerable plastic facility. These wall-mounted assemblages sample a range of references, such as from the scholar Aby Warburg’s archive of late 19th Century American West photographs, which Pendleton juxtaposes with word fragments drawn from an associative list. Formally, the assemblages consist of silkscreens of the images and letters onto mirrors and clear glass, placing them within boxes, allowing Pendleton to create a fresh mode of display and presentation that delinks the visual imagery from their prior historical and material contexts and the words form their usual semantic and signifying relations. Individually and together they merit repeated viewing, so I hope to see some more of them soon at another Pendleton exhibit.

No comments:

Post a Comment