Tuesday, December 25, 2018

Thursday, October 04, 2018

Orlando Watt's Recital of "Words" Excerpt

Many years, shortly after I first discovered YouTube, which probably would have been not long before I began blogging here, I had the idea to begin posting short clips of myself reading poems by other poets that I loved. Then clarity struck and I realized that this would mean that I'd have to film myself reading the poems, and my naturally shyness, technical ignorance and concern for violating unknown copyright strictures got the better of me, and that idea remained just that. Of course countless other people decided to do something similar, as well as recording their own poems specifically for a YouTube viewership, so I would have hardly been alone in this project. Not long after Seismosis, my collaboration with poet and artist Christopher Stackhouse, appeared, someone named Kinomode created a lovely short video, inspired by the book, that I deeply enjoyed. If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, inspiration drawn from a pre-existing work is one of the finest tributes. When the Black Poets Speak Out movement, organized by Ebony Stewart and Amanda Johnson, began, I originally planned to contribute a video, but shyness overtook me, and so my support was with them, but in the realms of concept and affect.

Fast forward to recently, when I received a request for a list of YouTube URLs to videos of me reading or discussing my work. There aren't many, but I dutifully compiled what existed, and sent them along. (There is or was one on Vimeo, I think, pairing Chris and me as we read from Seismosis; I still had dreadlocks then, and over the years I periodically have encountered younger poets who found the recitation in unison thrilling. That was directly inspired by one of my dazzlingly smart former Northwestern undergraduate students, Tai Little, who wrote a senior thesis novella that included a double-columned passage that she invited classmates to perform live; it was thrilling to hear, and in fact embodied the disorientation she was aiming to convey in her narrative.) At any rate, in my YouTube search I came across something I had never seen before, which was someone reciting one of my poems, and I have to say, I love it.

I do not know the performer, a young man named Orlando Watt. But he takes my poem "Words," which appeared earlier this year on the Academy of American Poets Poetry Daily website, and brings it to life in his own distinctive way. I have read the poem a number of times, very differently from, but it was a delight to see and hear his take, using a brief excerpt of the poem as a monologue, perhaps for an audition. His accent and the way he paces the words and shifts the emphases got me to think about what I had written and how the music in my head transferred to and was transformable on the page. Now that I am posting the link to the video here, I also will post a note of thank you below the video itself. And maybe, if I can find the time and now that cellphones are much easier to handle than the older digital video cameras, post a few videos of myself reading poems--by others!

Fast forward to recently, when I received a request for a list of YouTube URLs to videos of me reading or discussing my work. There aren't many, but I dutifully compiled what existed, and sent them along. (There is or was one on Vimeo, I think, pairing Chris and me as we read from Seismosis; I still had dreadlocks then, and over the years I periodically have encountered younger poets who found the recitation in unison thrilling. That was directly inspired by one of my dazzlingly smart former Northwestern undergraduate students, Tai Little, who wrote a senior thesis novella that included a double-columned passage that she invited classmates to perform live; it was thrilling to hear, and in fact embodied the disorientation she was aiming to convey in her narrative.) At any rate, in my YouTube search I came across something I had never seen before, which was someone reciting one of my poems, and I have to say, I love it.

I do not know the performer, a young man named Orlando Watt. But he takes my poem "Words," which appeared earlier this year on the Academy of American Poets Poetry Daily website, and brings it to life in his own distinctive way. I have read the poem a number of times, very differently from, but it was a delight to see and hear his take, using a brief excerpt of the poem as a monologue, perhaps for an audition. His accent and the way he paces the words and shifts the emphases got me to think about what I had written and how the music in my head transferred to and was transformable on the page. Now that I am posting the link to the video here, I also will post a note of thank you below the video itself. And maybe, if I can find the time and now that cellphones are much easier to handle than the older digital video cameras, post a few videos of myself reading poems--by others!

Sunday, September 30, 2018

Farewell, Victory Hall/Drawing Rooms on Grand Street

|

| The sign outside Drawing Rooms' former site |

One aspect of Jersey City that particularly has interested since moving here over two decades ago is the small but vibrant arts communities that has managed to thrive in the shadow of New York City's far larger global art-industrial-complex world just across the Hudson. Jersey City's downtown, part of which was once dubbed the Powerhouse Arts District, once was full of warehouses and lofts where artists could and did live and work quite affordably, particularly compared to Manhattan and even Brooklyn. Many of the older buildings have been razed for new towers, which began rising in the lead up to the 2007-9 financial crisis, and once again began rising in 2011-12, or they were repurposed for rich condo buyers, as the downtown has steadily gentrified, scattering artists to nearby districts and cities, like Newark. A few organizations and a good number of artists have managed to hang on.

One, Victory Hall Inc., began hosting a series of programs in 2011 under the rubric of Drawing Rooms, a contemporary arts center in what was a former convent next to the campus of St. Peter's Preparatory High School, near the Paulus Hook neighborhood of Jersey City. Drawing Rooms hosted a range of shows of "two and three-dimensional works"--drawings, paintings, mix-media works, sculptures of various kinds--as well as performances by emerging and mid-career artists based in the metro area Its focus on local artists, especially those from Jersey City, Hudson County and northern New Jersey, has been heartening. Some have gone on to shows a bigger galleries in New York and elsewhere, but Drawing Rooms never lost the intimacy of its exhibition spaces, the informality and friendliness of the staff, or the affordability of works on display, for those interested in buying it. All of these set it apart even from most smaller galleries in the City.

What I learned once I started dropping by Drawings Rooms's shows, which run regularly throughout the year, was that its parent organization, Victory Hall, comprises more than Drawing Rooms, however; its other programs include Rainbow Thursdays Artists, art classes for local developmentally disabled adults; Artist Workspaces, hosted in Drawing Rooms and other sites in Jersey City; Victory Hall Press, which published original catalogues of work by Victory Hall-affiliated artists; Victory Arts Public Projects, which have included partnering efforts with other local organizations; and The Art Project, shows and gallery tours organized for four new condo developments, in conjunction with Shuster Development, in downtown Jersey City: Art House, The Oakman, Hamilton House and Gallery at 109 Columbus. (I have to say that while I understand how politics and economics have changed the equation for not-for-profit arts organizations, pushing all but the wealthiest to the brink, it still pains me a bit to witness the very institutions squeezed out or suffocated by gentrification partnering with gentrifiers in order to stay alive and keep a foothold in the very spaces and places they alone once brought to life. Neoliberal capitalism is something else, and this pattern has repeated itself over and over, I know.)

As of June 15, however, Drawing Rooms will no longer occupy its ex-convent home; it had previously announced that it would be moving to the Topps Building/Mana Campus in the Journal Square neighborhood of Jersey City. (The Mana Campus is part of Mana Contemporary, the contemporary arts powerhouse in Chicago and Miami. In preparation for its move, Drawing Rooms held a two-day final celebration and fundraiser, titled "Somewhere Over the Rainbow & Prospero's Grand St. Masque," which included an art sale, so I headed over during the second day's Brunch session to spend a little time with the artworks and artists, including James Pustorino, the Executive Director, and Anne Trauben, Exhibitions Director/Curator, who work I featured on here back in 2013, when I read poems based on them as part of a Halloween event. For the Masque, Drawing Rooms had taken its aesthetic design from Edgar Allan Poe's famous 1842 story "The Masque of the Red Death," and decorated the rooms in the colors delineated in the tale, with two additional ones, yellow for an eighth room, and red for the hallway, signifying not death and morbidity, but a rainbow's promise and ephemerality.

It was encouraging to see how many people were there that Sunday, and to later learn that a number of the artworks did sell. Below are some photos from the event; you can find the names and titles on the Masque link above. if you are in Jersey City and want to see some of the artists whose work has been featured at Drawing Rooms, Drawing Rooms' new exhibits, "Now Ya See It, Now Ya Don't" and will open this upcoming weekend at the new gallery in the Topps Building, and there will also be an Artists' Studio Tour, including Art Project exhibits at the Art Project sites listed above.

|

| The sandwich board out front |

|

| Some of the artwork (I can't remember which color designated this room) |

|

| Artworks by (l-r) an unknown artist, Cathy Diamond, Gregory Stone, and Brian Hallas |

|

| Patrons and supporters of Victory Hall & Drawing Rooms |

|

| More artwork, at left by Robyn Feld and Andrew B. Cohen, two at right by god@daddy borja |

|

| Conversations amid the art |

|

| Works in the Yellow Room (I think), by Barbara Lubliner (fourth from left), an unknown artist, and Joan Mellon (at far right), |

|

| Works by Anne Trauben (left) and Joan Mellon (right) |

|

| Conversations in one of the galleries |

|

| The Black Room |

|

| Some of the art in it |

|

| Viewing the art up close |

|

| The now former home of Drawing Rooms |

Tuesday, September 04, 2018

Maryanne Wolf on the Death of (and Ways to Protect) Deep Reading

When journalist Nicholas Carr’s The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains appeared in 2010, I remember exchanging emails with Reggie H. and Lisa M. about it, reading numerous articles about it (including excerpts from the book) online, and eventually buying the book to dive fully into what he had to say. Overwhelmed at the time by my usual mountain of required reading it took me a while to get to it, but I did, and found his argument about the effects of the Internet on our brain and neural system quite persuasive. I even blogged a snippet from The Shallows at the end of that year. To quote Carr again:

One very recent entry in this genre is Maryanne Wolf's Reader, Come Home (Harper Collins, 2018), which takes up some of the threads of her earlier books, Proust and the Squid (Harper Collins, 2011), and Tales of Literacy for the 21st Century (Oxford University Press, 2016), with a shift, as was the case with Carr, on online reading and its effects. Her earlier books explored the origins of human literacy and the challenges that our long human history of interacting with text faced as we moved into our current millennium, but now Wolf, Director of Center for Reading and Language Research at Tufts University, where she is Associate Professor of Child Development, and thus someone steeped in the current state of research on reading, is concerned with reading itself. As Laura Miller describes in her recent Slate review of the book, Wolf began to notice something about her own experience as a reader that I'd noted anecdotally with some of my students, beginning perhaps roughly 10 years ago and increasing among them to the point that I had to rethink my syllabus and approach to teaching: a waning ability to concentrate, and engage in sustained, "deep reading."

And it was not just my students: even for me, I have begun at times to feel a creeping distraction and impatience at any online text that was too long or complex ("tl;dr"), with a resulting desultory engagement in response. When it comes to expansive online texts, the feeling waxes. Skim, leap, surf: shift from one open page to another, one link to another, expect that the headline and the first few paragraphs will supply you with all you need to know. Earlier this year, as I had witnessed among my undergraduates, I even found myself struggling to get into novels, growing impatient after only a few pages, something I had never experienced befored. Wolf felt something similar, bemoaning her own inability to stick with a long, complex text, which is to say, a work not unlike a great deal of literature in a variety of genres written for hundreds of years. This was one of the central points Carr had broached back in 2010--as had Wolf, in turns out, in her 2011 Guardian essay "Will the speed of online thought deplete our analytic thought?", citing none other than Marshall McLuhan, who'd suggested that the medium was the "massage" and the message, that the technology would not only serve as a vessel but shape what it brought to us, and would shape our understanding of it.

In her new book, Wolf specifically recounts the experience of testing her capacity to "deep read" by returning to a novel she'd loved when she was younger, the very dense, multilayered Magister Ludi (The Glass Bead Game), German Nobel Laureate Hermann Hesse's 1943 futuristic magnum opus about a group of monk-like intellectuals who retire to a fictional European country known as Castalia, sequestered from most technology and economics, where they run a school for boys and engage in a complex, profoundly subtle form of play, the eponymous Glass Bead Game, that requires a lifetime of study and reflection to perfect. As she recounts, she tried repeatedly to begin it, but could not, yet it was not as if she could not read anything; online texts she sailed, or rather skimmed through. Hesse's novel, however, proved to be a tremendous struggle, and she temporarily set it aside. As an experiment, she set aside a period each day in which she would try again to read it, and, lo and behold, she began to find that after an extended period of struggle, she not only could get into Hesse's novel, but was carried away by it, her mind now in deep reading mode.

As note above, I have seen what Wolf is describing increasingly not just with my students and in my own recent reading habits, but with friends, one of whom admitted not to have read a novel by another writer in a while. The first person buys books of fiction and nonfiction, but when I ask if they have read them, the reply is, No. In terms of my own reading this spring and summer, I've had to force myself not to set the book aside after a few pages to check email or Twitter or look up something on Google, yet when I have stuck with the books. I get transported into the world of the work. This has been the case with novels and collections of short stories by Tayari Jones, Tommy Orange, Rachel Cusk, Uzodinma Iweala, Matthias Énard, Nafissa Thompson-Spires, Jamel Brinkley, Celeste Ng, and Beatriz Bracher, to name just a few of them, as well as various longer works I have blurbed or read for judging projects. I enjoyed every last one of them, but initially entering each was more difficult than it ever had been in the past.

So, you might say, Who cares if no one reads long or dense or long, dense works of fiction any more? What happens if we lose the "cognitive patience" and focus that Wolf argues we may be losing? Hesse's writing and ways of thought may have reached their ends in terms of their possibility of connection--or, to put it more simply--relatability, with contemporary readers. (As someone with a propensity for for dense prose and serpentine syntax, this is not an idle concern.) Even if that's true, what Wolf--like Carr--shows, as prior studies have borne out, is that "deep reading," and the virtual engagement with narratives have powerful, beneficial cognitive effects. One is to foster a capacity for analysis, which texts by Hesse, or the authors I list above, or Marcel Proust, the subject of Wolf's first book, require. To put it another way, every complex work is a kind of detective story, leaving clues the reader must assemble to make sense of the work, even as we are relating it to and contextualizing it with what we already know. The second is a quite powerful feature of fiction writing in particular: empathy. When we enter the minds, perspectives, bodies, and experiences of others in fiction, we connect with them, even if briefly, and this shapes our own views in the wider world. It sounds like hocus-pocus, but it isn't. Literature's emotional power should never be underestimated. But the fact remains, even the simplest works of fiction--and nonfiction--are slow, or at least slower than tiled or laddering screens. You can skip a few sentences or flip a pages ahead but you've probably missed something important--that is, unless you're reading a book like Julio Cortázar's Hopscotch (Rayuela), where this is an integral feature of the novel.

Rather than categorically decrying digital reading, what Wolf suggests is that even if it is reshaping our brain and cognition, there is a way, particularly for those with children or teaching and working with them, to ensure that they learn and engage not only with screens, but with books, so that they don't lose the deep reading facility altogether. For adults, will power and a concerted effort to put digital devices away--and turn off TV screens--is probably the easier and best option. Cultivating this "bi-literate" brain is what Wolf is aiming for. How to do this will a challenge for the future, especially how many people cannot pull themselves away from their phones, especially younger ones. I tend to take a gentle approach with my students in terms of their in-class texting, urging them not to do so, but also recognizing that at times they may have a pressing issue they need to address. On the other hand, I also try to remind myself that I, like most people on this earth when I was in school from age 5 to roughly 32 or so, nearly a decade out of the classroom as part of that mix, made it through entire days without 1) ever picking up a telephone unless it was an emergency and 2) only talking about things on a screen, unless we were watching a video or TV program as part of our less, or doing something very specific on a computer required for class. How did we survive? I did, we did, and I place this thought in the forefront of my brain as I close my laptop, shut off my phone, and dive into another book--a novel, a collection of poetry, short stories or essays, a play. But I'll get to that as soon as I post and read a few Tweets, bookmark a YouTube video, watch a few Instagram stories, and look at one more article online....

The Net's cacophony of stimuli short-circuits both conscious and unconscious thought, preventing our minds from thinking either deeply or creatively. Our brains turn into simple signal-processing units, quickly shepherding information into consciousness and then back out again.He was certainly on to something crucial about the various cognitive changed spurred by the US's increasing digital turn, and he wasn't alone in his assessment. Others like internet pioneer and guru Jaron Lanier took up related arguments about the effects not just of the net and our brains and nervous system, but the entire e-technological apparatus and its transformation of human sociality, economics, and our contemporary polity. Where Carr was alarmist--now proving to have been correct in his worries--Lanier was more measured, but in both cases, as with others who have written about the effects of the net, social media, etc., they were identifying the songs of more than one canary in the coal mine we're now deeply immersed in.

One very recent entry in this genre is Maryanne Wolf's Reader, Come Home (Harper Collins, 2018), which takes up some of the threads of her earlier books, Proust and the Squid (Harper Collins, 2011), and Tales of Literacy for the 21st Century (Oxford University Press, 2016), with a shift, as was the case with Carr, on online reading and its effects. Her earlier books explored the origins of human literacy and the challenges that our long human history of interacting with text faced as we moved into our current millennium, but now Wolf, Director of Center for Reading and Language Research at Tufts University, where she is Associate Professor of Child Development, and thus someone steeped in the current state of research on reading, is concerned with reading itself. As Laura Miller describes in her recent Slate review of the book, Wolf began to notice something about her own experience as a reader that I'd noted anecdotally with some of my students, beginning perhaps roughly 10 years ago and increasing among them to the point that I had to rethink my syllabus and approach to teaching: a waning ability to concentrate, and engage in sustained, "deep reading."

And it was not just my students: even for me, I have begun at times to feel a creeping distraction and impatience at any online text that was too long or complex ("tl;dr"), with a resulting desultory engagement in response. When it comes to expansive online texts, the feeling waxes. Skim, leap, surf: shift from one open page to another, one link to another, expect that the headline and the first few paragraphs will supply you with all you need to know. Earlier this year, as I had witnessed among my undergraduates, I even found myself struggling to get into novels, growing impatient after only a few pages, something I had never experienced befored. Wolf felt something similar, bemoaning her own inability to stick with a long, complex text, which is to say, a work not unlike a great deal of literature in a variety of genres written for hundreds of years. This was one of the central points Carr had broached back in 2010--as had Wolf, in turns out, in her 2011 Guardian essay "Will the speed of online thought deplete our analytic thought?", citing none other than Marshall McLuhan, who'd suggested that the medium was the "massage" and the message, that the technology would not only serve as a vessel but shape what it brought to us, and would shape our understanding of it.

In her new book, Wolf specifically recounts the experience of testing her capacity to "deep read" by returning to a novel she'd loved when she was younger, the very dense, multilayered Magister Ludi (The Glass Bead Game), German Nobel Laureate Hermann Hesse's 1943 futuristic magnum opus about a group of monk-like intellectuals who retire to a fictional European country known as Castalia, sequestered from most technology and economics, where they run a school for boys and engage in a complex, profoundly subtle form of play, the eponymous Glass Bead Game, that requires a lifetime of study and reflection to perfect. As she recounts, she tried repeatedly to begin it, but could not, yet it was not as if she could not read anything; online texts she sailed, or rather skimmed through. Hesse's novel, however, proved to be a tremendous struggle, and she temporarily set it aside. As an experiment, she set aside a period each day in which she would try again to read it, and, lo and behold, she began to find that after an extended period of struggle, she not only could get into Hesse's novel, but was carried away by it, her mind now in deep reading mode.

As note above, I have seen what Wolf is describing increasingly not just with my students and in my own recent reading habits, but with friends, one of whom admitted not to have read a novel by another writer in a while. The first person buys books of fiction and nonfiction, but when I ask if they have read them, the reply is, No. In terms of my own reading this spring and summer, I've had to force myself not to set the book aside after a few pages to check email or Twitter or look up something on Google, yet when I have stuck with the books. I get transported into the world of the work. This has been the case with novels and collections of short stories by Tayari Jones, Tommy Orange, Rachel Cusk, Uzodinma Iweala, Matthias Énard, Nafissa Thompson-Spires, Jamel Brinkley, Celeste Ng, and Beatriz Bracher, to name just a few of them, as well as various longer works I have blurbed or read for judging projects. I enjoyed every last one of them, but initially entering each was more difficult than it ever had been in the past.

So, you might say, Who cares if no one reads long or dense or long, dense works of fiction any more? What happens if we lose the "cognitive patience" and focus that Wolf argues we may be losing? Hesse's writing and ways of thought may have reached their ends in terms of their possibility of connection--or, to put it more simply--relatability, with contemporary readers. (As someone with a propensity for for dense prose and serpentine syntax, this is not an idle concern.) Even if that's true, what Wolf--like Carr--shows, as prior studies have borne out, is that "deep reading," and the virtual engagement with narratives have powerful, beneficial cognitive effects. One is to foster a capacity for analysis, which texts by Hesse, or the authors I list above, or Marcel Proust, the subject of Wolf's first book, require. To put it another way, every complex work is a kind of detective story, leaving clues the reader must assemble to make sense of the work, even as we are relating it to and contextualizing it with what we already know. The second is a quite powerful feature of fiction writing in particular: empathy. When we enter the minds, perspectives, bodies, and experiences of others in fiction, we connect with them, even if briefly, and this shapes our own views in the wider world. It sounds like hocus-pocus, but it isn't. Literature's emotional power should never be underestimated. But the fact remains, even the simplest works of fiction--and nonfiction--are slow, or at least slower than tiled or laddering screens. You can skip a few sentences or flip a pages ahead but you've probably missed something important--that is, unless you're reading a book like Julio Cortázar's Hopscotch (Rayuela), where this is an integral feature of the novel.

Rather than categorically decrying digital reading, what Wolf suggests is that even if it is reshaping our brain and cognition, there is a way, particularly for those with children or teaching and working with them, to ensure that they learn and engage not only with screens, but with books, so that they don't lose the deep reading facility altogether. For adults, will power and a concerted effort to put digital devices away--and turn off TV screens--is probably the easier and best option. Cultivating this "bi-literate" brain is what Wolf is aiming for. How to do this will a challenge for the future, especially how many people cannot pull themselves away from their phones, especially younger ones. I tend to take a gentle approach with my students in terms of their in-class texting, urging them not to do so, but also recognizing that at times they may have a pressing issue they need to address. On the other hand, I also try to remind myself that I, like most people on this earth when I was in school from age 5 to roughly 32 or so, nearly a decade out of the classroom as part of that mix, made it through entire days without 1) ever picking up a telephone unless it was an emergency and 2) only talking about things on a screen, unless we were watching a video or TV program as part of our less, or doing something very specific on a computer required for class. How did we survive? I did, we did, and I place this thought in the forefront of my brain as I close my laptop, shut off my phone, and dive into another book--a novel, a collection of poetry, short stories or essays, a play. But I'll get to that as soon as I post and read a few Tweets, bookmark a YouTube video, watch a few Instagram stories, and look at one more article online....

Saturday, September 01, 2018

Farewell, Village Voice

For the last decade or so, I have only occasionally read Village Voice, mostly online, but once upon a time, when I was in my 20s and living in Boston, acquiring a copy of the Voice at one of the news stands there, and perusing it to find out what was happening in New York, was one of the highlights of my week. (Back then I also read the New York Times in print almost every day too.) The Voice provided a trove of news about politics, in New York and beyond, as well as some of the most invigorating criticism about art, entertainment, the broader culture and the world, that you might find anywhere. For me it constantly outmatched Boston's own Phoenix, that city's alternative paper, and was part of a national ecosystem of similar papers that offered fresh, often left-leaning and progressive but always counter-mainstream perspectives on the state of the world. Now, the Voice is gone.

It's where I first learned about New York's legendary Public Theater and its pathblazing directors Joseph Papp and George C. Wolfe; it was one of the mainstream places where I regularly found informative reportage, Andrew Kopkind, Richard Goldstein and others, about about HIV and AIDS. It was a regular-go to learn about the newest and less common films, books, music, theater and performances of all kinds. The Voice also brought to me and countless readers original photography (Sylvia Plachy, C. Carr, etc.), cartoons by Jules Feiffer, Ted Rall, Lynda Barry, Mark Alan Stamaty, and Tom Tomorrow, and literature (I recollect reading a story by the great poet Elizabeth Alexander's there, among other gems). I was enthralled by Greg Tate's, Joan Morgan's and Gary Indiana's criticism, and when my friend Scott Poulson-Bryant (now Dr. Poulson-Bryant, and a professor at Fordham University) secured an internship and then a job there, it seemed like an unimaginably wonderful thing had occurred. Other than Greg Tate, the one columnist I made sure never to miss was Michael Musto, whose tour through NYC's once inimitable queer club scene will probably never be equalled again.

When C and I moved to the New York area, the Voice remained a paper I rarely missed reading. I'd even looked in its ads section in my search for an apartment when heading to NYU. When Annotations appeared, a young writer named Colson Whitehead wrote one of the most insightful, praiseworthy reviews the book received, and it meant everything to me that it appeared in the Voice. When the Voice became free in New York in 1996--which I loved but also figured was a bad sign--I would grab a copy in Manhattan before heading back to New Jersey, where we still had to pay for them. Yet I also paid attention to the labor strife that was wracking the paper in 2005 and 2006, and again in 2013: editors fired or resigning, writers sharing their fears over decreased benefits and the new owners' tunnel vision, and worse. Even as its leadership changed, the Voice remained one of the rare news organs that seemed not to coddle the rich and powerful--I recall Wayne Barrett's extensive reporting on Rudy Giuliani's administration, and the time it ran an article outing New York's conservative Catholic Cardinal Edward Egan--and continued to employ incisive writers like Steven Thrasher. Yet in the end, its most recent owner, and the shifts in the media industry, ensured its demise.

Established in 1955 by Dan Wolf, Ed Fancher, John Willcock, and Norman Mailer, the Voice was the US's first alternative weekly, and received a wide array of honors over its 63-year existence, including Pulitzer Prizes, National Press, and George Polk awards. It survived a number of owners over the years, until it was sold in October 2015, by its penultimate owner, Voice Media Group, to billionaire heir Peter Barbey. In August 2017, the Voice announced it would cease to exist as a print publication, and its final print issue appeared on September 17, 2015. Although Barbey said that he wanted to save the Voice, and despite his considerable financial reserves, he claimed that financial exigencies required him to shut down the paper, even as he allegedly has been searching for someone to buy it. Yesterday, the electronic edition ceased publication, half the staff were laid off, and those who remain will assist for a limited period in archiving the paper's rich store of articles and materials. Yet the fact remains that one of the once truly vital organs of reportage, investigation and criticism, for New York, the US and the globe, is gone, and with it passes an era--many really--that we will somebody

Established in 1955 by Dan Wolf, Ed Fancher, John Willcock, and Norman Mailer, the Voice was the US's first alternative weekly, and received a wide array of honors over its 63-year existence, including Pulitzer Prizes, National Press, and George Polk awards. It survived a number of owners over the years, until it was sold in October 2015, by its penultimate owner, Voice Media Group, to billionaire heir Peter Barbey. In August 2017, the Voice announced it would cease to exist as a print publication, and its final print issue appeared on September 17, 2015. Although Barbey said that he wanted to save the Voice, and despite his considerable financial reserves, he claimed that financial exigencies required him to shut down the paper, even as he allegedly has been searching for someone to buy it. Yesterday, the electronic edition ceased publication, half the staff were laid off, and those who remain will assist for a limited period in archiving the paper's rich store of articles and materials. Yet the fact remains that one of the once truly vital organs of reportage, investigation and criticism, for New York, the US and the globe, is gone, and with it passes an era--many really--that we will somebody

Friday, August 17, 2018

Aretha Franklin, Queen of Soul

Though I knew she had been ill for some time, it was still a shock to hear that Aretha Franklin (1942-2018) had moved to hospice care earlier this week and that yesterday, she passed away in Detroit. One of the greatest, most vocally gifted and agile singers of her generation or any other, with a rich, layered mezzo-soprano voice that could project with tremendous power and draw emotion out of each note, she set the standard for her peers and all who followed her, earning the title of the Queen of Soul in 1964. But as she proved throughout her career, in addition to possessing major talent as a pianist, she also could sing gospel, the musical genre she grew up hearing and learning in the church, New Bethel Baptist, led by her legendary father, Rev. C. L. Franklin; R&B, in which she became a superstar; pop, leading to her early fame; the blues, which suffused all of her music; rock & roll, as she proved in the 1970s; jazz; and even classical operatic music, as she demonstrated to the world (though close friends like Grace Bumbry knew it) when she stepped in for Luciano Pavarotti on national TV and sang "Nessun Dorma" at the 1998 Grammys.

A path blazer as a woman in the music industry who at age 12 joined her father on his "gospel caravan" tour, Franklin also received acclaim as a strong supporter of the US Civil Rights Movement and of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., joining him on tour when she was 16, and singing at his funeral after his assassination in 1968. She attempted to post bond for Angela Davis after her arrest, and remained an ardent supporter of the Black fight for civil rights and equality, not just in the US but in South Africa and across the globe. After moving back to Detroit to take care of her ailing father, who had been shot twice at point blank in his home, she kept the city as her chief residence, supporting local artists and its communities through her philanthropy. LGBTQ equality was among the many other causes Franklin championed. (This summary only scratches the surface of her life, which included considerable challenges from childhood on through her final illness.)

Her catalogue includes over 40 studio-produced albums, twenty Billboard Number 1 singles, beginning with "I Never Loved a Man (The Way I Love You)" in 1967 through "Freeway of Love" in 1985, and countless awards and honors, including 17 Grammys in categories ranging from Best Female R&B Performance to Best Soul Gospel Performance to Best Traditional R&B performance; Grammys Legend, Lifetime Achievement and MusiCares Person of the Year awards; American Music Awards; NAACP Image Awards; Kennedy Center Honors (she was the youngest person to receive the award when honored in 1994); the first woman inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, in 1987; induction into the Rhythm & Blues Music Hall of Fame and GMA Gospel Music Hall of Fame; and a 1981 star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. I would be remiss if I did not mention her brief but unforgettable turn in the iconic 1980 movie The Blues Brothers, in which she sang "Think," which won her a whole new slew of younger fans. Though she has now left the mortal plane, her music, perennial and enduring in its beauty and power, will always be with us as testimony to her greatness.

Here are some videos of Aretha Franklin performing some of her countless hits. May she rest in peace and sing on in the great beyond.

Aretha Franklin - Spanish Harlem (Single Version 45rpm / 1971) / HD 720p

Luther Vandross & Aretha Franklin - A house is not a home (live)

Aretha Franklin - Amazing Grace (Live 2014)

Aretha Franklin at Barack Obama's Inauguration, January 2009

Aretha Franklin - I Say A Little Prayer: her very best performance, October 9, 1970

Aretha Franklin Nessun Dorma Grammys 1998

Aretha Franklin & James Brown - Please, Please, Please - Soul Session - 1987

Respect - Aretha Franklin, 1967

Aretha Franklin - Chain Of Fools Live (1968)

Aretha Franklin - Think (feat. The Blues Brothers) - 1080p Full HD

Aretha Franklin - Bridge Over Troubled Water

Watch Aretha Franklin Make President Obama Emotional, Kennedy Center Honors, 2015

Aretha Franklin - Mary Don’t You Weep - Soul Train - 1979

Aretha Franklin - Freeway Of Love (Video)

Who's Zoomin' Who?, 1985, Sony Music Entertainment

Aretha Franklin - Rolling in the Deep / Ain't No Mountain Live Adele Cover Version

Aretha Franklin "(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction", 1st Festival international de jazz à Antibes, ORTF, 1970.

Aretha Franklin, Jimmy Lee, 1986, Sony Music Entertainment

Thursday, August 16, 2018

Annotations Playlist (by Keith Ridgway)

One of the joys of the internet, and of Twitter--horrible social media platform though it sometimes can be--is the serendipity of coming across positive public notes and links, among them responses others might have to your work and you that you might otherwise not see. I appreciate these especially at a time when letters and even emails are less common than they once were. (I have never received many letters from readers, positive or negative, let alone emails, concerning my work, at least without something else being involved, like an invitation to read or a request for a blurb.)

The other day, after signing on to Twitter, I saw that I had about 8 notifications, and once I clicked on the button, I saw the following post, by the great Irish author Keith Ridgway, whose Hawthorn & Child (New Directions, 2013) I thought was one of the best and most original novels of that year. It is an anti-detective novel in the best way, and exquisitely written, with sections of such striking strangeness I had to read them again. For whatever reason--its freshness? its queerness?--it did not receive the attention it deserved when it appeared. (Perhaps some forward-thinking British director will make it into a feature film, with David Oyelowo, David Gyasi, Daniel Kaluuya, Ashley Walters, Aml Ameen, Gary Carr, David Ajala, or Jimmy Akingbola, to name just a few the talented British actors out there, starring as the eponymous Child, and Max Rhyser, Simon Woods, Jeremy Sheffield, Kieron Richardson, or Andrew Hayden-Smith, to name some of their counterparts, as Hawthorn.)

Scrolling through the thread, I saw he'd posed a prior question:

As he realized, no one had recently--I seem to recall someone doing many moons ago, perhaps in the mid-00s?--so he compiled one himself, on Spotify, the streaming music service I have to admit to having never signed up for. (I only signed up for Last.fm among the more recent streaming services, and, some years back, Naxos, which basically streams album clips of classical European and American art music with some jazz.) He culled most of the musical references, and this is the marvelous playlist he came up with:

You can access it here even if you aren't signed up for Spotify.

Keith Ridgway expertly includes references from the direct mentions of standards, like Ahmad Jamal's "Poinciana" and Thelonious Monk's "Pannonica" to more subtle ones like "Afro Sheen," which is both the hair product and a song, as he shows, by Stephen Sechi. Another reference he susses out is "Dance of the Infidels," by Bud Powell, and he selects Josephine Baker's stirring "De Temps En Temps" in response to a reference to Baker in the text. (She was a native St. Louisan.)

There are some not on the list, like John Coltrane's "Naima," though "Ruby, My Dear" is here, and the R&B references, to Marvin Gaye and The Stylistics, are also in the mix alongside all the jazz. Reading his list and listening to the snippets was almost surreal, as it carried me back to my father's immense record collection when I was growing up in the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s and early 1980s, the exact time span of Annotations. It also gives deeper insight into the sound- and cultural world of the novel-memoir, and for that, I offer my deepest thanks to Keith Ridgway, and urge Spotifiers to check it out!

The other day, after signing on to Twitter, I saw that I had about 8 notifications, and once I clicked on the button, I saw the following post, by the great Irish author Keith Ridgway, whose Hawthorn & Child (New Directions, 2013) I thought was one of the best and most original novels of that year. It is an anti-detective novel in the best way, and exquisitely written, with sections of such striking strangeness I had to read them again. For whatever reason--its freshness? its queerness?--it did not receive the attention it deserved when it appeared. (Perhaps some forward-thinking British director will make it into a feature film, with David Oyelowo, David Gyasi, Daniel Kaluuya, Ashley Walters, Aml Ameen, Gary Carr, David Ajala, or Jimmy Akingbola, to name just a few the talented British actors out there, starring as the eponymous Child, and Max Rhyser, Simon Woods, Jeremy Sheffield, Kieron Richardson, or Andrew Hayden-Smith, to name some of their counterparts, as Hawthorn.)

Scrolling through the thread, I saw he'd posed a prior question:

As he realized, no one had recently--I seem to recall someone doing many moons ago, perhaps in the mid-00s?--so he compiled one himself, on Spotify, the streaming music service I have to admit to having never signed up for. (I only signed up for Last.fm among the more recent streaming services, and, some years back, Naxos, which basically streams album clips of classical European and American art music with some jazz.) He culled most of the musical references, and this is the marvelous playlist he came up with:

You can access it here even if you aren't signed up for Spotify.

Keith Ridgway expertly includes references from the direct mentions of standards, like Ahmad Jamal's "Poinciana" and Thelonious Monk's "Pannonica" to more subtle ones like "Afro Sheen," which is both the hair product and a song, as he shows, by Stephen Sechi. Another reference he susses out is "Dance of the Infidels," by Bud Powell, and he selects Josephine Baker's stirring "De Temps En Temps" in response to a reference to Baker in the text. (She was a native St. Louisan.)

There are some not on the list, like John Coltrane's "Naima," though "Ruby, My Dear" is here, and the R&B references, to Marvin Gaye and The Stylistics, are also in the mix alongside all the jazz. Reading his list and listening to the snippets was almost surreal, as it carried me back to my father's immense record collection when I was growing up in the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s and early 1980s, the exact time span of Annotations. It also gives deeper insight into the sound- and cultural world of the novel-memoir, and for that, I offer my deepest thanks to Keith Ridgway, and urge Spotifiers to check it out!

Wednesday, August 08, 2018

Terence Nance's *Random Acts of Flyness*

|

| Terence Nash (Jemal Countess/ Getty Images), from Colorlines |

Random Acts of Flyness is a sketch series, a video show, a quirky and queer, postmodern comic anthology and cavalcade, stitched together--or not--by Nance's dream logic. I say his dreams, since he's directing, co-writing and executive producing, but it's clear he has gathered around him a very talented group of creative minds. (I should add that I the show's movement also reflects the associative, often desultory logic of contemporary social media. Au courant it is.) For Nance there are binding threads, however gosssamer: an impressively original ear and eye, a profound interest in blackness in its various conceptual possibilities, an aim to explore anti-nihilistic critiques in new, dramatic forms, and a willingness, from the sole episode I've seen, to see how far a comic idea, however bizarre can go. The result is a show that exemplifies a radical act of black aesthetic freedom, of the kind that most viewers are not going to see even on semi-regular basis otherwise.

|

| Tonya Pinkins as Ripa the Reaper, Random Acts of Flyness, HBO |

Take, for example, the first episode's mock cable show skit "Everybody Dies," featuring Ripa the Reaper (Tonya Pinkins, props to her for even agreeing to this), who sends up the idea of black death, ushering people, particularly black children, through a door marked life and out one--shoving them at one point--marked death, as she repeatedly draws out a ditty about how we'll all die set to the tune of "Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star," accompanied by what sounds like a toy piano. (When two white children join the queue, she sends them back, to a different fate she cannot determine.) Everyone dies, the sketch shows, but not equally, and the perverse spectacle of children dying defies any attempts to make (too much) light of it. Eventually we see Ripa the Reaper's exhaustion at and surrender to the absurdity of what she has to participate in, a powerful dramatic correlative to our affective responses to spectacles of black death we all witness daily. Watching it I thought, only a very talented black writer--and actor--could pull this off, and Nance--and Pinkins--did.

I won't go so far as to say that every element of Random Acts of Flyness's--why do I want to keep calling it Radical Acts of Freedom?--debut worked, though. Nance's opening gambit, "What Are Your Thoughts on Raising Free Black Children?" which involves him riding a bike and getting stopped by a cop who demands that he stop filming what's happening, at first felt almost too obvious, even though what he was dramatizing happens so regularly it has almost become a cliché, despite its often violent and mortal outcome. To his credit, Nance did not end the segment where you might expect, and his flight--literal and figurative--ultimately did feel satisfying, no least because, in a different but consonant way, the idea animates a great deal of my collection Counternarratives. The strands of African and African American folklore that come together as Nance soars underscored for me both his creative skill and how unlike most TV this show probably will be.

|

| Jon Hamm in a skit on Random Acts of Flyness, HBO |

Another clip, "White Be Gone," featuring actor Jon Hamm rubbing a shoe polish-like black unction into his temples to eradicate "white thoughts" also felt a bit belabored, and made me wonder whom it was geared towards, since surrounding it were other clips, like "Black Face(s)" and an exploration of black sexuality, that seemed geared specifically to black viewers. (In fact, I had the thought at one point that the show ought to be on TV One or BET since Nance seemed to be speaking so directly, and lovingly, to other black folks.) Given the daring of some of the other sketches, I actually expected Hamm to cover his entire face, and eventually send up a kind of black-face liberalness or wannabe wokeness, though perhaps that might have gotten the show canceled and Hamm's career nixed, however evident the sarcasm. And yet given the video clips on "Black Face," contra "blackface," Nance had already established the terms to go even further.

|

| Copyright © HBO |

I will continue watching, though. I expect to be surprised, wowed, enthralled, nonplussed. This is defamiliarization in practice, as praxis. As was the case with Boots Riley's Sorry to Bother You, or Arthur Jafa's very different but sublime Love Is the Message, The Message Is Death, I feel profoundly attuned to what Nance is undertaking, even if I have no idea sometimes what he's up to or where he will head. But I am looking forward to continuing on the journey with him. (Random Acts of Flyness airs on HBO on Friday nights/Saturday mornings at midnight.)

Tuesday, August 07, 2018

Boots Riley's *Sorry To Bother You*

Codeswitching, and more specifically the act of African Americans using a "white voice," including accent, intonation and pitch, to meet the expectations of white teachers, employers, colleagues and the broader society, is a culturally and politically informed practice now extensively discussed in the public discourse. Any number of writers, politicians, rappers, and other figures have explored codeswitching; there is even an NPR program with that title. It also provides a thread in numerous current TV and cinematic shows--think of Issa Rae's Insecure, Kenya Barris blackish or Donald Glover's Atlanta--but Boots Riley, a 47-year-old musician, artist and filmmaker from Oakland, makes it the central premise of his first full-length feature, Sorry to Bother You, and what a dope film he has dreamt up! It requires no hyperbole to say that Sorry to Bother You is easily the most original and unpredictable feature of this year--or many years. In it, Riley takes the idea and practice of his premise literally, so literally in fact that it quickly shifts into productively absurd territory, only to keep ramping things up from there. (Riley makes great use of literalism's formal and conceptual possibilities.) The result is a speculative, progressive, Afrofuturist, fantasia that manages to produce laughter, provoke thought, and present far-too-rare onscreen plight of working-class people, transracial and ethnic labor solidarity, the voraciousness and utter lack of ethics of US conglomerates, and the perverse, almost science-fictionally rotten core of contemporary capitalism.

|

| Lakeith Stanfield as Cash Green & Tessa Thompson as Detroit |

|

| Omari Hardwick as Mr. ________ |

|

| Stanfield and Armie Hammer, as Steve Lift |

|

| LaKeith Stanfield as Cash |

|

| Steve Yeun as Squeeze |

|

| Thompson, featuring Detroit's amazing earrings |

|

| Jermaine Fowler as Salvador, Yeun and Stanfield |

Thursday, August 02, 2018

Quote: James Baldwin

|

| James Baldwin (Associated Press) |

--James Baldwin (born on August 2, 1924), from "James Baldwin: The Art of Fiction, No. 78," interviewed by Jordan Elgrably, The Paris Review, Issue 91, Spring 1984.

Monday, July 30, 2018

Grace Note: Albies & Acuña

Initial social media comments suggested that Albies was consoling his friend after the passing of Acuña's mother, but subsequent reports now state that Acuña mother is still alive. The video provoked some backlash, including predictable outbursts of gay panic and homophobia. Whatever the reasons behind the gesture, it something we rarely see in sports, and thus beautiful and remarkable. It also underlines that there are other ways of expressing friendship, love and comfort between men that counter the norms of rigid, fragile and toxic masculinities. It's also noteworthy and significant, I think, that both of these men are of African descent. May they and their careers flourish!

|

| Teammates Ozzie Albies and Ronald Acuña Jr. |

Random Photos

Following up on my post of 2018 photos from mid-June, here are few more recent photos from the last few months. Enjoy!

|

| 14th Street & 8th Avenue, Manhattan |

|

| The view from New Directions's offices, late spring, Manhattan |

|

| At the New Directions Book Expo American annual party, Manhattan |

|

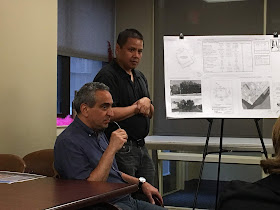

| At a neighborhood association meeting, to stop a monstrosity from going up on our street |

|

| One of the endlessly rising towers, downtown Jersey City |

|

| Waiting for a ride, Jersey City |

|

| Filming an ad, Jersey City |

|

| Outside Berl's Poetry Store, DUMBO, Brooklyn |

|

| Amid the prosperity, Jersey City |

|

| Empire State Building, Manhattan |

|

| Another closed store I used to pop by, Manhattan |

|

| Praying, on busy 8th Avenue, Manhattan |

|

| Repairs, Exchange Place Station, Jersey City |

|

| Waiting for the 6, Upper East Side, Manhattan |

|

| Street poet, near Astor Place, West Village, Manhattan |

|

| Crossing 5th Avenue, West Village, Manhattan |

|

| Cyclists, 5th Avenue, West Village, Manhattan |

|

| A new high(er) end business, 8th Street (formerly "Shoe Row"), West Village, Manhattan |

|

| 8th Street, with empty storefronts, West Village |

|

| Another empty storefront, 8th Street, West Village |

|

| Bleecker & Christopher Sts., West Village |

|

| A can collector, in front of another empty storefront, Christopher Street, West Village |

|

| Rows of empty storefronts, Christopher Street, West Village |

|

| The beautiful letter press edition of my poem "all music," by Daniela Del Mar and letterpress-printed at her shop, Letra Chueca Press in Portland, as part of my visit to Reed College and presentation to Samiya Bashir and her students |

|

| Construction on what was formerly NYU's Coles Athletic Center, with the Silver Towers in the rear, West Village, Manhattan |

|

| Mercer Street, with one of my favorite used bookstores in Manhattan, Mercer Street Books, which has managed to hang on (please visit them if you're in town) |