|

| Carlos Fuentes, at home in Mexico, 2001 (Henry Romero/Reuters) |

In the mid-1980s,

Carlos Fuentes (1928-2011) was at the height of his fame. He had published a dozen novels, many formally experimental, including a handful that made and cemented his reputation, among them his début,

Where the Air Is Clear (

La Región Más Transparente, 1958);

Aura (1961), which continues to be censored in certain countries;

The Hydra Head (

La Cabeza de La Hidra, 1978); and his masterpieces

The Death of Artemio Cruz (

La Muerte de Artemio Cruz, 1962);

Terra Nostra (1975), a work not unlike

Gabriel García Márquez's

One Hundred Years of Solitude (

Cien Años de la Soledad, 1970) in its scope and ambition; and

The Old Gringo (

Gringo viejo, 1985), a shorter novel reiminaging the life of writer

Ambrose Bierce that garnered tremendous attention and readership in the

United States, a country in which Fuentes, one of Mexico's leading authors, had spent many years, including part of his childhood. He had also by that point published four collections of short stories and five collections of essays, and written four plays and seven or so screenplays. The honors he received for his work steadily increased, from the

Xavier Villaurrutia Award in 1976 to the

Mexican National Prize for Arts and Sciences in 1984, and a few years later he would win what is arguably the most important prize for a Spanish-language author, the

Miguel de Cervantes Prize, in 1987. But this period was significant for another reason: Fuentes had begun to teach at a number of American universities, and it was during one of these stints that I was able to take an undergraduate class with him, an experience that made a profound impression on me and led me, perhaps, to a life of writing and teaching myself.

Fuentes held, I believe, an august chair for visiting writers, and taught a lecture course that permitted him to expound, in magisterial fashion, on all sorts of subjects. The specifics, I must admit, I do not remember. But I vividly recall how he would hold forth, in each class, on stage before a vast crowd, how he wove together a narrative that seemed to capture everything in its net, how he looked and acted the part of an international man of letters, of the engaged writer, which he had been and still was. Tall, handsome, witty, able to range across languages, to cite authors and ideas without recourse to notes, no name dropper but someone who actually

knew and had worked with the people he was invoking, he truly loomed larger than life. I had no idea at that time that he'd been a

Communist in his youth and a supporter of

Fidel Castro and the

Cuban Revolution, though I did know his general ideological orientation was on the left, and that his work, as in

Where the Air Is Clear and

The Death of Artemio Cruz, openly critique the

Mexican elite and governing classes, as well as Mexican history itself. But Fuentes had gone much further; a diplomat from 1965 on, he resigned as Ambassador to the

UK to protest the 1968 massacre of students in

Mexico City, and left the foreign service in 1977 to protest the appointment of

Gustavo Díaz Ordaz, the president of Mexico during the 1968 assault, as Ambassador to

Spain. Morever, Fuentes refused the 1972

Mazatlán Literature Prize to protest the Mexican state of

Sinoloa's actions against students at the

State University of Sinaloa. (Such actions sparked criticism within Mexico's commentariat; in 1988, writer

Enrique Krauze deemed Fuentes the "guerilla dandy.") I don't think he ever mentioned any of this in his lectures, but it was clear that he stood against dictators and democratically-enabled tyrants both (and this included not only Mexico's long dominant

Institutional Revolutionary Party and its leaders, but

Hugo Chávez of

Venezuela and

George W. Bush as well), and that literature, even if seemingly not overtly political, might stand as a bulwark against both. As I said, the specifics of the course I have mostly forgotten, but the model he set is one I have taken to heart, even if I have not thus far been able to come anywhere close to it.

One of my favorite Carlos Fuentes stories entails something I did not personally witness, but which I heard and have recounted many times to fellow writers and to students to let them know that, when they feel they are so deep in a poem or story or novel chapter they almost feel they're in another world, that it's perfectly okay. It may be utterly apocryphal, but bear with me nevertheless. Supposedly Fuentes was visiting

Rome, perhaps on vacation, and was in his room in the middle of the day. The chambermaid came to clean the room, and as she approached the door, she could hear raised voices, and then what sounded like a violent argument. A man was yelling, passionately, and then his voice fell to a normal tone, and then another voice, likely a woman's, responded, with fury. This went on for a while, the voices going back and forth, the tempest between them such that the worker thought twice about knocking, let alone opening the door. She also wondered whether she ought contact the concierge, or security, so passionate were the exchanges at certain points. Other guests staying on the hall paused momentarily at the brouhaha, and went on their way. But finally the voices died down, and she proceeded to rap on the door to find out if she could enter. The gentleman who opened the door beckoned her in. The chambermaid, expecting to see a woman seated somewhere in the room, in a chair, on the bed, peering at the man from an interior doorway, saw instead only him, and a sheaf of papers, on the bedspread, some of them fanned out as just tossed down. The man was clutching a few. The chambermaid asked the gentleman if everything was okay, for she had accidentally overheard a fiercesome quarrel. The gentleman smiled and reassured her that all was fine. There was only he in the room; the quarrel was his reading through his novel, still underway, his voice animating those of the characters. This gentleman, this writer, was Carlos Fuentes.

|

| Carlos Fuentes, Union Sq., 1995 (AP Photo/Rick Maiman, File) |

Fuentes, one of the pilots of the

Boom movement in

Latin American literature, which placed numerous fictional works from across the Hispanophone global south on the literary landscape, was tipped to win the

Nobel Prize in Literature several times; his compatriot, the poet

Octavio Paz, did win it, in 1990, as did Fuentes's friend, García Márquez, in 1982, but the great Mexican fiction writer did not. (Instead, the most recent Hispanophone writer to receive the award was the right-leaning

Mario Vargas Llosa, of Peru, in 2010.) Not that this oversight stopped Fuentes. He kept pouring forth fiction, essays, occasional pieces, everything, publishing the English translation of

his 2003 novel, The Eagle's Throne (La Silla del Águila) last year, and an essay on the French election in Mexico's

Reforma newspaper the day he died. His finest works, and the example he set, both in his fiction and criticism, and as a public literary and cultural figure, an ambassador of the word in the fullest sense, will endure. So too will his importance to the literature of his country, a multifaceted portrait of Mexico taking shape in and through his works, and to all writing across Latin America, and the Americas. Carlos Fuentes passed away in a hospital in Mexico City on Tuesday. He was 83 years old.

***

|

| Brooke-Rose, 1970 |

Perhaps as publicly and widely acclaimed as Fuentes was, so obscure and little known in contrast was, and remains,

Christine Brooke-Rose (1923-2011), a writer almost his exact peer, and nearly as prolific too, with 17 novels to her name, and many other works of short fiction, nonfiction, literary translation, and academic literary criticism.

Brooke-Rose passed two months ago, on March 21, at the age of 89. Fuentes was, from the very beginning,

experimental in terms of form; perhaps not as experimental, say, as Mexican writers such as

Fernando del Paso or

Daniel Sada, whom I mentioned in a previous post, but no straightforward realist either.

The Death of Artemio Cruz, for example, is narrated by a dead man, shifts in time and voice, and uses the second person to great effect;

Christopher Unborn begins, in Sternian fashion, before the character leaves the womb;

Destiny and Desire, I believe, is narrated by a severed head. But Brooke-Rose went much, much further. She is, by an easy mark, one of the most innovative writers in English-language prose in the late 20th century, and

sui generis in Anglophone letters in many ways, for she went beyond diegetic experimentation to the level of grammar itself, pushing the limits of

how one might tell stories as a way of embodying the deeper themes and critical possibilities of those stories, and the enacting the concepts underpinning them.

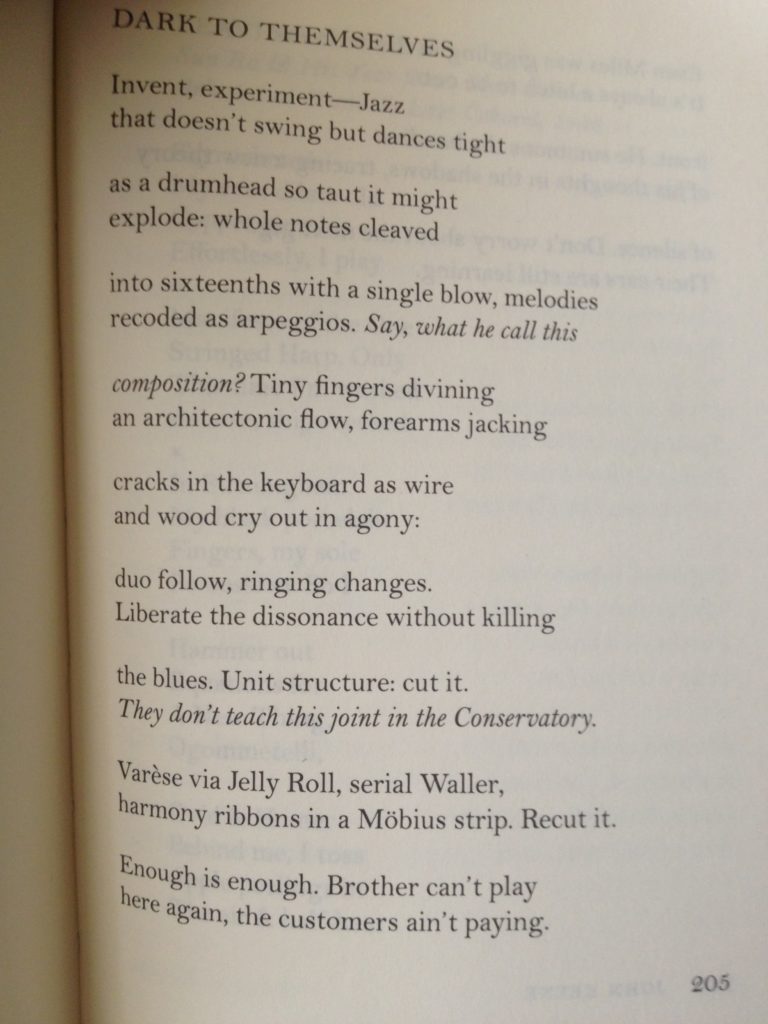

What do I mean? One of the techniques Brooke-Rose played with was the

lipogram. In the hands of a number of writers affiliated with the

Ouvroir de littérature potentielle (Oulipo), this lipogrammatic technique, of leaving out a

letter, say, across an entire work, presented a constraint that they could nevertheless resolve. Thus there's the famous example of

Georges Perec's

La disparution (

A Void), which eschews the most frequently used letter in the French language, "e"--which is also, interestingly enough, the most frequently used letter in English as well. (In the prior sentence alone, "e" appears 32 or so times.) Quite a challenge. But Brooke-Rose extended the lipogram to the grammatical level, and thus in her novel

Between, which explores the experiences of a translator, she leaves out the most common

verb in the English language, which happens to be the verb..."to be." That is, the copulative verb ("I am a writer," "She's hungry," "Are you there?" etc.), also used for the past voice ("I was led to believe you had emailed me"), progressive tenses ("We're heading there now"), and so forth, one of those English language tools, learned at the earliest stages of language acquisition, to which a speaker and writer learns she can attach a subject and predicate and turn anything into a sentence--is missing, in this entire novel. Note of course the multilayered irony of a novel about a translator, a woman trapped between languages (and names, places, everything) without recourse to the very verb--the grammatical form signifying

action-- that elementally connects and binds in most European languages, titled "Between."

Such was Brooke-Rose's genius. And she did this again and again. She wrote novels exploring the language and the concept of discourse itself (

Out, 1964;

Such, 1966;

Thru, 1975;

Amalgamemnon, 1984), novels that treated questions of cybernetics and the dawning digital age (

Xorandor, 1986;

Verbivore, 1990;

Textermination, 1991), novels that reimagined the human (

Next, 1998;

Subscript, 1999), and a very personal, autobiographical works that hovered between genres (

Remake, 1996

; Life, End Of, 2006)

. Before she wrote any of these, she had already published conventional works in poetry, prose and criticism (

Gold: A Poem, 1955

; The Languages of Love, 1957

; A Grammar of Metaphor, 1958), and then several satirical novels (

The Sycamore Tree, 1958

; The Dear Deceit, 1960

; The Middlemen: A Satire, 1968), but it was with

Out that she went truly out beyond almost anything most of her British peers, save a few (

J. H. Prynne; B.S. Johnson;

Ann Quin; David Jones;

Basil Bunting; etc.) were up to, creating an post-apocalyptic world that turned racial identification on its head. Subsequent novels involved leaving out the verb

to have (

Next); requiring readers to construct, as with a puzzle, the narrative

(Thru); writing a work narrated by rocks speaking in what approximates computer language (

Xorandor); and picturing a convention, in the United States, in which characters from famous novels convened, absent their authors, with pandemonium breaking loose (

Textermination). It is therefore fair to say that Brooke-Rose not only pushed formal boundaries but those of content as well, making many of her works a challenge for readers, and this, coupled with the fact that she spent a great deal of her career teaching in

France, and with the fact that while she explicated the likes of writers like

Ezra Pound and

speculative fiction writers and

Harlan Ellison yet spent little time, at least until the end, explicating her own work (which of course should have been left to the works themselves, and to others), and because she was a woman writing the sort of work that men usually get all the acclaim for, she has been critically underexplored and popularly underread.

Her own account of her life is worth savoring, so I'll offer a few points that suggest another reason both for her linguistic curiosity and for her lack of attention. Brooke-Rose was born in

Geneva, Switzerland, to an English father and an American-Swiss mother, and grew up mostly in

Brussels, Belgium--think of all the languages she was coming into contact with--where she received her education, later heading to

Somerville College, Oxford University and

University College, London. Already gifted with linguistic ability, she worked as a

Women's Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) in intelligence at

Bletchley Park, the UK's main decryption center during

World War II, and after the war's end, completed her degree, married, and worked as a journalist and author. Divorced in 1968, she took a position teaching at the

University of Paris-Vincennes, the radical, experimental campus outside Paris, and taught there till 1988. Throughout this period, she published steadily and with no loss of imaginative daring, though her only major award came in 1966, when she received the

James Tait Black Memorial Prize for

Such.

More than once when I have students who turn out to be voracious readers and are seeking out anything that will challenge them, and I hope to get them past the writers they are more likely than not to encounter, contemporary and past, I will recommend Brooke-Rose. I have thus far never had a student tell me that she or he took to Brooke-Rose's work as they have to novels by

George Saunders, or

Cormac McCarthy, or

Renee Gladman, or

Nalo Hopkinson, or

Kenzaburo Oe, or

Maryse Condé, or

Ricardo Piglia, or any of the other people I have sent them off to explore. For numerous reasons, the gantlets she throws down are too difficult to tender. (I find the same to be the case with another British experimentalist,

J.G. Ballard, whose unparalledly strange vision also never ceases to astonish me.) Or maybe other reasons are at play. I do know that I have found her work enthralling at times, and often quite funny.

Life, End Of, even as its textures steep with sorrow because it's clear the author has reached the end of her life, is nevertheless so compelling I found it hard to put down, and I felt the same way about

Remake, which tells a personal tale so dramatic and delicious that many a lurid nonfiction writer would be hard-pressed to match it. Then there are her experiments in the speculative realm, which some writers might devote an entire career too. The novels of the late 1960s, on the other hand, should have dissertationists reaching for their (the books') spines. This very well may be occurring somewhere. I don't know.

I do know that in her equally heartbreaking collection of essays,

Invisible Author: Last Essays, which, after I finished it, I believe I had to run and call

Tisa B. I was so struck by the frustration infusing it, Brooke-Rose points out how almost

none of her academic critics ever seemed to be able to figure out what she was doing, instead noodling off on one or other points. She even laid this at the doorstep of a champion,

Hélène Cixous, about whom I'll say no more. Instead, I urge people to read Brooke-Rose, perhaps beginning with

Remake and

Life, End Of (which leave out the pronoun "I"), and then,

Out and

Textermination. If you dare take up her dare, keep jumping around her fiction after that. Your brain will get a workout, a very good one. And you'll keep the memory of her dazzling originality,

sadly too little heralded, alive.