As I watched the Academy Award-nominated film Incendies (2010) last month, which my friend writer and translator N. had recommended, the impression I began to feel taking shaping was that I was observing the sort of movie Costa-Gavras or Gilles Pontecorvo might make if either had spent half his life watching telenovelas. I invoke the popular TV form, though without question you could go much further back in time and art to find plots turning on lurid, almost implausible revelations by such greats as Sophocles and Euripides, or, moving forward by many centuries, William Shakespeare, who like his predecessors traced out the seemingly coincidentally monstrous not only in the world at large, but within families themselves. The genius of each of these writers with such material lies in part in their skilfulness in taking what in lesser hands might come off as meretricious and elevating it to the level of the highest art, through mastery of the form of tragedy, through depth of characterization, through language itself. Incendies' director, Denis Villeneuve, who adapted the screenplay with script consultant Valérie Beaugrand-Champagne from an original play by Wajdi Mouawad, is no Shakespeare—and who is or needs be?--and he also but he does show considerable adroitness wedding the political and the melodramatic successfully in this film, which unfolds like an informative and disturbing puzzle that you cannot pull yourself away from.

Set in Canada and an unnamed country that bears more than a few resemblances to Lebanon, Incendies tracks the story of fraternal Arab-Canadian twins, sister Jeanne Marwan (Mélissa Desormeaux-Poulin), a promising mathematics graduate student, and brother Simon Marwan (Maxim Gaudette), a surly laborer, who have recently lost their emotionally remote but loving mother, Nawal Marwan (Lubna Azabal), and whom Jean Lebel (Rémy Girard), a sober white notary for whom Nawal worked for many years, have summoned to his offices for the reading of their mother's will. Both siblings expect little in the way of an estate from their former parent, the only one they have ever known, particularly because of the catatonia she entered at the end of her life, but Notary Lebel presents each with an envelope that Nawal dictated to him on her deathbed, and has a third that can only be opened once each addresses the requests in their respective envelopes. For Jeanne, the request is to give the letter to their brother, while for Simon, it is to give the letter to their father, both especially difficult requests because Nawal has never spoken of another child, let alone a son, or given the children any information about their father, at all.

Despite their grief, anger and misgivings, first Jeanne and then the formerly indifferent Simon head off for their mother's unnamed homeland, where, after a series of revelations and immersion in a lifeworld that Nawal, for reasons that become evident, hid from them, they encounter not only the truth of her past, but their own, in the history of her country, their country too, it turns out, what has been riven by civil war, sectarian war. Through a deftly braided narrative, Jeanne and Simon learn of that the sectarianism tore open not only the soil beneath their feet and the families around them, but the very mind, body and soul of their mother. By the film's end, they also understand not only their mother in ways that were inconceivable before, but themselves as well, and I mean this not in the clichéd sense, but corporeally and psychologically. What sends their mother into silence are truths that societies have for centuries, rightly I would argue under the circumstances, kept buried beyond the grasp of the speakable.

I shall avoid spoilers, but it should suffice to say that the horrors of Incendies derive not only from the sorts of murders and torture that occur in a war, but from the backdrop of inhumanity, anti-humanity really, that ideologies, religious, political, and so forth, can and sadly far too often do provoke. Nawal is a Christian, and as in Lebanon, the country cleaved on multiple ideological lines. Like Costa-Gavras, Villeneuve is able both to depict the political conflicts both with enough clarity to allow us to grasp them, but also with the murkiness that even those involved in them might feel. He shows, rather than explains, a crucial and effective choice here, and in so doing forces us out of any easy identification, while also making us to experience a bit of the confusion and frustration that the political crises depicted demands. The actress Lubna Azabal inhabits Nawal as fully as is humanly possible, taking us from the traumas of her youth, when she sought to defy custom and elope with a Muslim, her first trangression against tribalism, conformism and orthodoxy, for which we see she and all around her will have to pay a high price, to her last breaths, sparing us none of the drama in between. Azabal impresses through her overall expressivity and physicality in every filmic moment in which she appears. At a certain unforgettable moment, when she saves her own life but fails to rescue a fellow bus passenger, Azabal's face becomes the scene of that unbearable, shattering loss within the larger scene of loss unfolding around her. At another point, when she is about to be subjected to an act so horrifying I could barely bear to think about it, Azabal beams out a quality diamondlike in its resolve, and broken though she may be, we grasp how she could have gone on to create a new life thousands of miles away.

As good, though perhaps with a less expressive facial range, is Desormeaux-Poulin, who plays Jeanne. The story comes to feel as much hers as her mothers. Gaudette, who plays Simon, is passable at best, and perhaps Villeneuve realized that given the plot, this had to be more the mother's and daughter's story—these women's stories—than those of the son(s), of men, even though it is men who create the grounds of terror through which all the characters must pass. Though he appears only a few times, Abdelghafour Elaaziz, as Abou Tarek, achieves unforgettable menace. Another of the film's triumphs is its cinematography; André Turpin captures the mutedness of the characters' emotional states in the colors used to render the Canada scenes, while the external scenes, such as during the busride through the mountain pass in the unnamed Muslim country, blaze out of the cinematic frame, and the interior scenes appeared, at least to me, to harbor innumerable shadows. When I left the darkened cinema, those shadows lingered, and though I know Incendies neither means embers or ashes, these metaphors respectively capture the the hopefulness of the film's ending, and the multiple tragedies the film often unbearably dramatizes.

Set in Canada and an unnamed country that bears more than a few resemblances to Lebanon, Incendies tracks the story of fraternal Arab-Canadian twins, sister Jeanne Marwan (Mélissa Desormeaux-Poulin), a promising mathematics graduate student, and brother Simon Marwan (Maxim Gaudette), a surly laborer, who have recently lost their emotionally remote but loving mother, Nawal Marwan (Lubna Azabal), and whom Jean Lebel (Rémy Girard), a sober white notary for whom Nawal worked for many years, have summoned to his offices for the reading of their mother's will. Both siblings expect little in the way of an estate from their former parent, the only one they have ever known, particularly because of the catatonia she entered at the end of her life, but Notary Lebel presents each with an envelope that Nawal dictated to him on her deathbed, and has a third that can only be opened once each addresses the requests in their respective envelopes. For Jeanne, the request is to give the letter to their brother, while for Simon, it is to give the letter to their father, both especially difficult requests because Nawal has never spoken of another child, let alone a son, or given the children any information about their father, at all.

Despite their grief, anger and misgivings, first Jeanne and then the formerly indifferent Simon head off for their mother's unnamed homeland, where, after a series of revelations and immersion in a lifeworld that Nawal, for reasons that become evident, hid from them, they encounter not only the truth of her past, but their own, in the history of her country, their country too, it turns out, what has been riven by civil war, sectarian war. Through a deftly braided narrative, Jeanne and Simon learn of that the sectarianism tore open not only the soil beneath their feet and the families around them, but the very mind, body and soul of their mother. By the film's end, they also understand not only their mother in ways that were inconceivable before, but themselves as well, and I mean this not in the clichéd sense, but corporeally and psychologically. What sends their mother into silence are truths that societies have for centuries, rightly I would argue under the circumstances, kept buried beyond the grasp of the speakable.

|

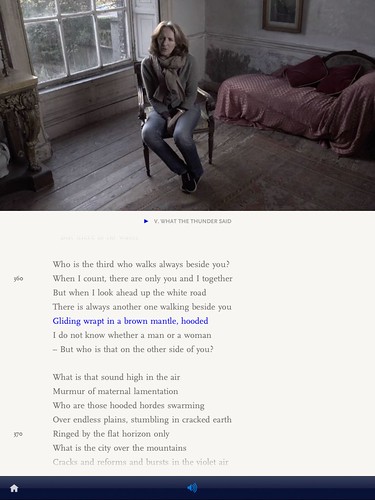

| Lubna Azabal as Nawal Marwan |

I shall avoid spoilers, but it should suffice to say that the horrors of Incendies derive not only from the sorts of murders and torture that occur in a war, but from the backdrop of inhumanity, anti-humanity really, that ideologies, religious, political, and so forth, can and sadly far too often do provoke. Nawal is a Christian, and as in Lebanon, the country cleaved on multiple ideological lines. Like Costa-Gavras, Villeneuve is able both to depict the political conflicts both with enough clarity to allow us to grasp them, but also with the murkiness that even those involved in them might feel. He shows, rather than explains, a crucial and effective choice here, and in so doing forces us out of any easy identification, while also making us to experience a bit of the confusion and frustration that the political crises depicted demands. The actress Lubna Azabal inhabits Nawal as fully as is humanly possible, taking us from the traumas of her youth, when she sought to defy custom and elope with a Muslim, her first trangression against tribalism, conformism and orthodoxy, for which we see she and all around her will have to pay a high price, to her last breaths, sparing us none of the drama in between. Azabal impresses through her overall expressivity and physicality in every filmic moment in which she appears. At a certain unforgettable moment, when she saves her own life but fails to rescue a fellow bus passenger, Azabal's face becomes the scene of that unbearable, shattering loss within the larger scene of loss unfolding around her. At another point, when she is about to be subjected to an act so horrifying I could barely bear to think about it, Azabal beams out a quality diamondlike in its resolve, and broken though she may be, we grasp how she could have gone on to create a new life thousands of miles away.

As good, though perhaps with a less expressive facial range, is Desormeaux-Poulin, who plays Jeanne. The story comes to feel as much hers as her mothers. Gaudette, who plays Simon, is passable at best, and perhaps Villeneuve realized that given the plot, this had to be more the mother's and daughter's story—these women's stories—than those of the son(s), of men, even though it is men who create the grounds of terror through which all the characters must pass. Though he appears only a few times, Abdelghafour Elaaziz, as Abou Tarek, achieves unforgettable menace. Another of the film's triumphs is its cinematography; André Turpin captures the mutedness of the characters' emotional states in the colors used to render the Canada scenes, while the external scenes, such as during the busride through the mountain pass in the unnamed Muslim country, blaze out of the cinematic frame, and the interior scenes appeared, at least to me, to harbor innumerable shadows. When I left the darkened cinema, those shadows lingered, and though I know Incendies neither means embers or ashes, these metaphors respectively capture the the hopefulness of the film's ending, and the multiple tragedies the film often unbearably dramatizes.